MOCA New York City (Museum of Chinese in America)

With so much focus on #BlackLivesMatter, it can be illuminating to look at other ethnic groups in the US. I visited MOCA New York City last year, and it’s high time I published my review.

I used to teach an American Studies overview course here in the Netherlands. Every year I made sure to point out to my students that Blacks are the only group that was brought to the US against their will. Nevertheless, there are many parallels in how different racial groups have been treated throughout US history, much of it based on simple racism.

Given that I used to teach history and American Studies, most of what I saw at the Museum of Chinese in America in New York City was information I already knew, at least in general terms. Nevertheless, the museum presents the history of the Chinese in America in a creative, engaging way. It had me slowing down and examining the exhibits more closely than I expected.

Disclosure: This article contains affiliate links. If you click on one of these links and spend any money, I will receive a small commission. This will not affect your price.

History of Chinese-Americans at MOCA New York City

The history of the Chinese in America is more complicated than it has often been presented. Of course much of that has to do with plain old racism and stereotypes about the Chinese. The exhibits at MOCA NYC show both the common stereotypes about the Chinese and the reality of their particular immigrant experience.

Large numbers of Chinese originally emigrated to California because of the Gold Rush, as I used to teach. MOCA New York, however, paints the wider picture. Chinese immigrants also worked in lots of other industries: fishing, farming, factory labor, and pretty much anywhere where they could make a living.

At the same time, while the labor movement gained traction in the Industrial Revolution, the Chinese were excluded from unions. Sometimes, when workers went on strike, the factory bosses hired Chinese workers as strikebreakers. At the same time, the unions stirred up racism against the Chinese as an enemy of labor and as a danger to society. So the Chinese were seen as a threat, not just by industry leaders and politicians, but also by other immigrant laborers.

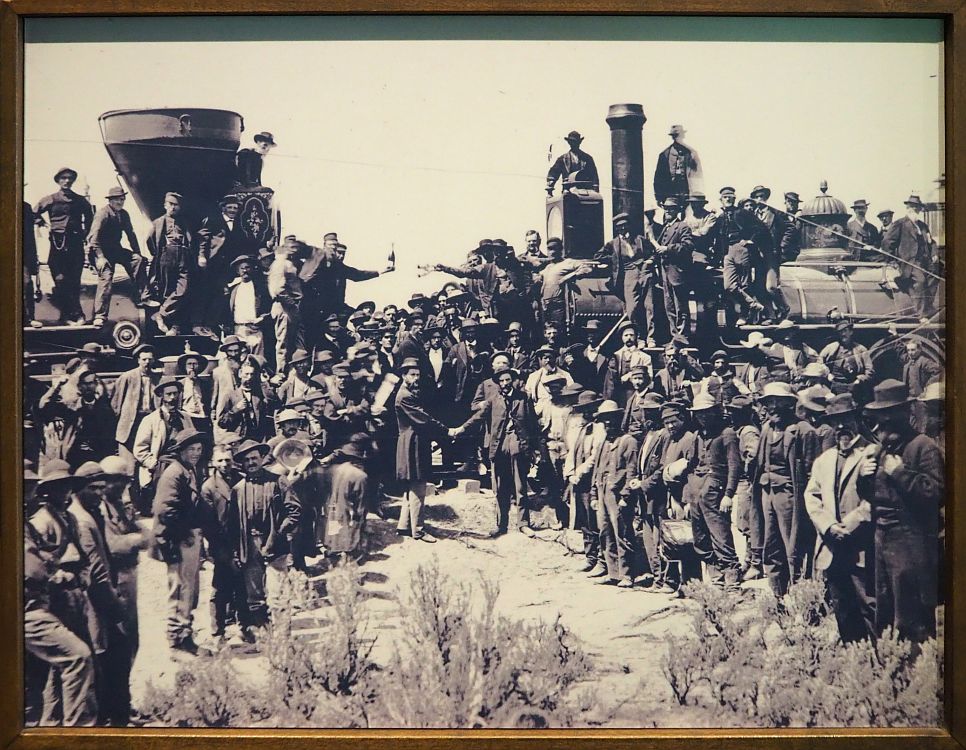

They were often invisible too. US history textbooks usually point out, for example, that Chinese laborers built the western half of the first transcontinental railroad. Yet a particular photo displayed in the museum shows how the Chinese were erased from the news coverage at the time. In this famous photo of a handshake in Promontory Summit, Utah Territory, where the two ends of the railroad met, no Chinese can be seen among the crowd.

An end to Chinese immigration

That’s just one example of anti-Chinese sentiment in the US. While anti-immigrant sentiment in general rose considerably toward the end of the 19th century, the treatment of Chinese was particularly harsh. Various laws limited their movements and opportunities until, ultimately, passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. This race-based law barred Chinese from entering the country.

This had a harsh effect on the Chinese immigrant community that was already in the US. Family members, for example, of men who had immigrated for work could not enter the country. Many men, already in the country, could not have families because intermarriage was illegal. As Chinese, they were also ineligible for citizenship.

You might also like these articles about New York City:

Chinese businesses in America

Many Chinese, both before and after the Chinese Exclusion Act, opened laundries or restaurants. Both were businesses they could start with little investment. A person could stay independent, unlike factory or other hourly work. Laundry was a job that was done by hand and, frankly, few other people wanted to do it. Chinese restaurants could play on the “exotic” theme, offering “chop suey,” which was cheap and became very popular. Each of these particular livelihoods has a small section of the museum devoted to it.

World War II and Chinese immigrant life

Things began to change during World War II. Because the US was allied with China, the Chinese Exclusion Act was a bit embarrassing politically. The act was lifted, yet ridiculously low quotas for Chinese immigration stayed in place: 105 Chinese people per year could immigrate.

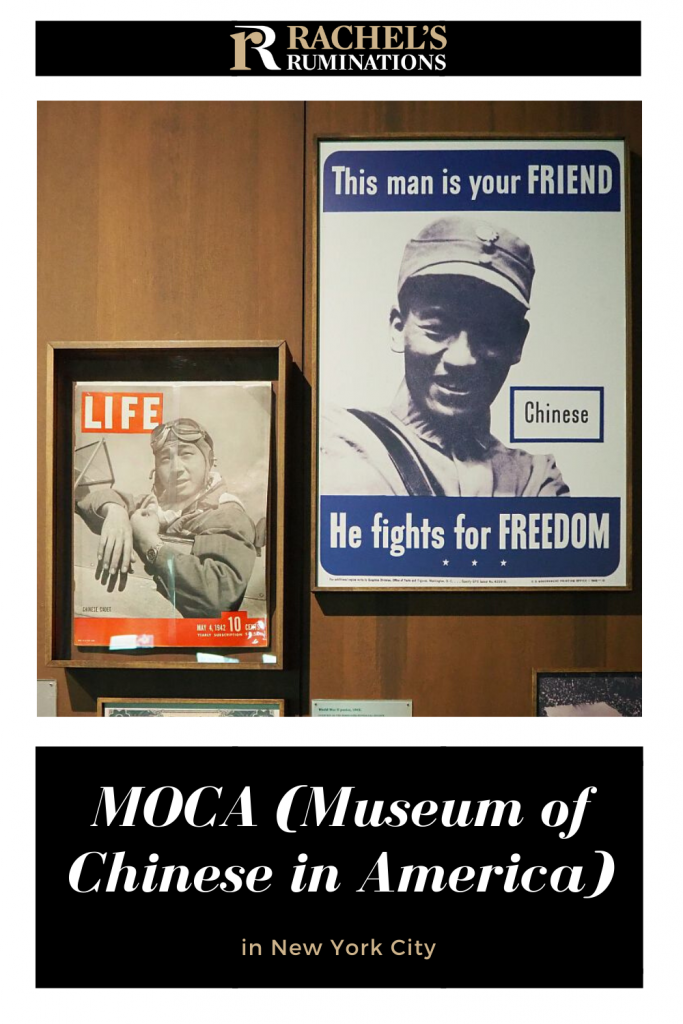

The section of the museum showing some of the kinds of propaganda that came out in the US during the war, aimed at changing attitudes toward the Chinese (but only a bit) is particularly striking. One magazine article, for example, speaks racist volumes: entitled “How to tell Japs from the Chinese,” it comes complete with annotated photos pointing out facial features.

The Chinese in America were, at any rate, finally eligible for citizenship. But real opening to immigration didn’t happen until the 1960s, when America’s entire immigration system changed. The new immigration laws still favored whites from northern Europe but nevertheless represented an improvement.

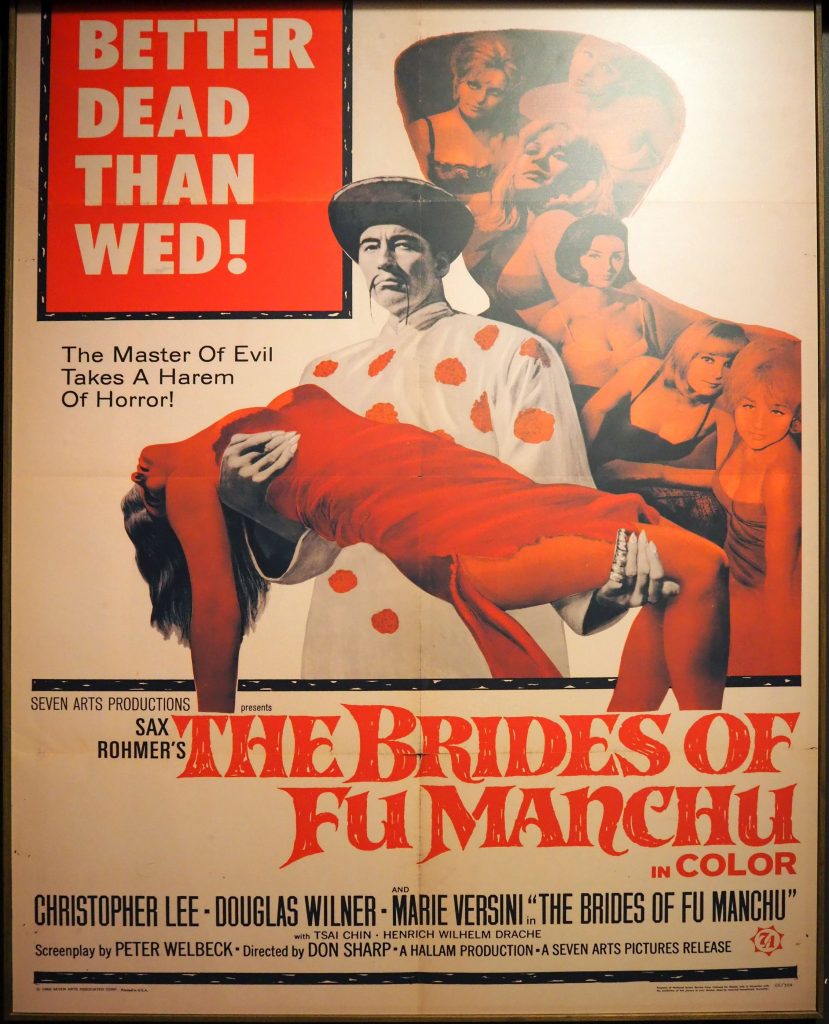

Another section of the museum explores the image of the Chinese as evil and exotic. This image was propagated first through imagery in newspapers and pamphlets and later through films, where the Chinese characters – usually villains like Fu Manchu – were often played by whites. To some extent this changed during the war, when the Japanese replaced the Chinese as the evil characters, still using white actors.

The “Model Minority” at MOCA NYC

The displays addressing the Chinese as a “model minority” illustrate a particular irony. Many Chinese families succeeded in becoming “Americanized” after World War II. At the same time, the new Chinese immigrants who started arriving later, after the new immigration system came into effect, were often already well-educated before they arrived, unlike earlier immigrants.

The Chinese rise into the middle class was used as a way to play ethnic groups off against each other and prevent them from joining forces during the Civil Rights Movement in the 60s. It manipulated Chinese families into distancing themselves from other minorities: “We’re like you whites, not like those disruptive black protesters.”

At the same time, the model minority myth helped white America claim colorblindness: “See? We’re not racist. The Chinese work hard and succeed. Why can’t you?”

The idea of the Chinese as hardworking and industrious, once considered a threat by labor unions because they were seen as dangerous competition aimed at taking over the country, was now used to describe them in a positive light, to put down other people of color. Keeping people of color divided didn’t always succeed in the 1960s. Today too the Black Lives Matter movement has clear multi-racial support.

My review of MOCA New York City

The museum focuses mostly on the history of the Chinese in America, as well as offering glimpses into the culture of the Chinese immigrant community, past and present. The building, designed by Maya Lin, is dramatic and well-suited for its purpose.

The Museum of the Chinese in America’s stated purpose is “to promote knowledge and understanding of the history and contributions of Chinese Americans.” It succeeds, in my view. The exhibits are clear, accessible and well-lighted, and include ample variety and multimedia elements to stay interesting. (Some of these are available online, including their audio tour. See their website.) It is a bit heavy on the reading + photos formula, but you can get the point from many of the illustrations, videos and audio without reading all of the explanatory signs.

Use this link to find accommodations in New York City!

Visiting MOCA NYC

MOCA New York City: 215 Centre Street, between Howard and Grant Streets, one block north of Canal Street. Two minutes’ walk from the Canal Street subway stop (lines N, Q, R, W, J, Z and 6). Seven minutes’ walk from Grand Street subway stop (lines B and D).

Open Tuesday-Sunday 11:00-18:00 and on Thursdays until 21:00.

Admission: Adults $12, children $8. On the first Thursday of each month, admission is free.

Speaking of admission, if you’re going to pack a lot of sights in New York City into a relatively short visit, it might save you some money if you buy a New York Pass. You can buy the pass based on the number of days you’ll be sightseeing. It activates the first time you use it.