Badagry, Nigeria’s slave trade history

While I was in Lagos for work, I took an extra day to visit Badagry, Nigeria. This town on the east side of Lagos was the “Point of No Return” in the Nigerian slave trade for 400 years. It is now home to three museums about the Badagry slave trade and Badagry history.

Our guide, Simon Stone Eyanam, met us in Badagry and introduced himself as a reggae musician. (You can see him under the name “Cornerstone” in this video.)

(Updated April 23, 2025)

Disclosure: This article contains affiliate links. If you make a purchase through one of them, I will receive a small commission.

Badagry slave trade museums

1. Williams Abass Slave Museum

Our first stop was Seriki Faremi Williams Abass Slave Museum; a “Brazilian Baracoon.” Built in the 1840s, this was, essentially, a warehouse for storing captives. Single-story, it consists of 40 rooms built around an open interior space with a well, still in use.

Each room, about three meters by three meters, originally had only one small window near the ceiling for ventilation, holding up to forty men, women and children. Sometimes they stayed there for months, awaiting purchase by Europeans who arrived by ship.

The museum itself only occupies a few of the rooms, while the rest are housing. The first museum room contains some of the instruments used to control the captives: original chains and manacles, for example.

History of Badagry slave trade

The guide pointed out that Africans carried out most of the African part of the slave trade, not Europeans. Slavery was already part of the culture when the Europeans first arrived in the 1400s. Either people became slaves when they were captured in wars or they were criminals, enslaved as punishment. At first, the Europeans could just trade for existing slaves.

The increasing European demand was what spurred Africans to continue capturing and selling slaves, which didn’t end until well into the 1800s. A thriving slave auction arose in Badagry, where slaves were exchanged for weapons, alcohol, and other products from Europe.

The second room of the museum is one of the original cells, and it was easy to imagine how nightmarish this would be with only that one small window—still there—and crowded with people for weeks or months on end, without a toilet or other sanitary facilities. Many died before even getting on the ships to cross the Atlantic.

I can only imagine how that period of imprisonment under such cruel conditions would break the captives’ spirits, if they survived.

Badagry’s Brazilian baracoon and Abass, its owner

Another room gave information about Seriki Williams Abass, the owner of the “baracoon.” Ironically, he had been a slave himself, and his owners took him to Brazil to be a domestic slave. They taught to read and write, which allowed them to send him back to Africa. There, he worked with his former owner as a slave trader. Even after the slave trade ended, he was a prominent and respected chief in Badagry.

Our guide told us of the intention of the Nigerian government to convert the entire former “baracoon” to a museum, but for now local families live in the former cells. They will eventually face eviction to accommodate the museum. Descendants of Abass own the building, so it is, for the moment, a private family museum. In the courtyard stands his tomb, along with the tomb of one of his many wives, presumably the first, or perhaps the favorite.

I found it interesting and a bit puzzling that his family still honors his memory in this way.

The Seriki Faremi Williams Abass Slave Museum: beside the Badagry post office. Open Monday-Saturday 9:00-17:30, Sunday 10:00-17:00.

We passed two cannons on the way to the next museum, just around the corner. According to our guide, a cannon was worth one hundred slaves, while a bottle of liquor was worth ten and a gun was worth thirty.

2. Mobee Slave Relics Museum in Badagry

Another museum, called Mobee Slave Relics Museum, also addresses slavery, and is, like the Abass museum, family-owned by descendants of a traditional chief who was a prominent slave trader. This one was High Chief Mobee, and I enjoyed the irony of his epitaph in this museum:

Just? An African who enslaved other Africans for sale to Europeans?

This museum consists of just one room, and the man who explained the objects around the room to us was, I think, a member of the family. He showed us the noisemaker that was used to announce the arrival of the chief, as well as telling us pretty much the same story of slavery that our guide had already told us. Like the other museum, this one has artworks illustrating how the captives were treated, and examples of chains and other implements of enslavement and torture.

The contrast between the lesson of these two museums – that slavery was nightmarish for the captives – and the evident pride and profit in being descendants of prominent slave traders is something that neither museum addressed directly. I found the conflicting messages striking.

Mobee Slave Relics Museum: on Mobee Street off of Hospital Road. Open Monday-Saturday 8:00-18:00 and Sunday 11:00-17:00.

The Point of No Return in the Badagry slave trade

When the European ships arrived, slave traders took the captives out of the jails and chained them together single-file, except for children, who they chained to their mothers. They took them by boat to Gberefu Island, just across a small distance of water. Originally, the slave traders used a traditional wooden canoe, but we crossed in a small motorboat with a dodgy motor.

Arriving on the island, the slave traders forced the slaves to follow a narrow path through a forest across to the ocean side of the island. It’s not far; I’d guess we walked a kilometer or so. Today it’s a scrubby, sandy path, and I found it difficult because of the heat and the deep sand. For the captives, it would have been a hundred times worse: weakened by their captivity, they were carrying the extra weight of the chains that bound them together and the fear and despair they must have felt.

We passed a “spirit well” on the path. This well was believed to cause anyone who drinks the water to forget their past. The captives were forced to take a drink before reaching their embarkation point. The sign next to it reads “Original spot slaves spirit attenuation well.”

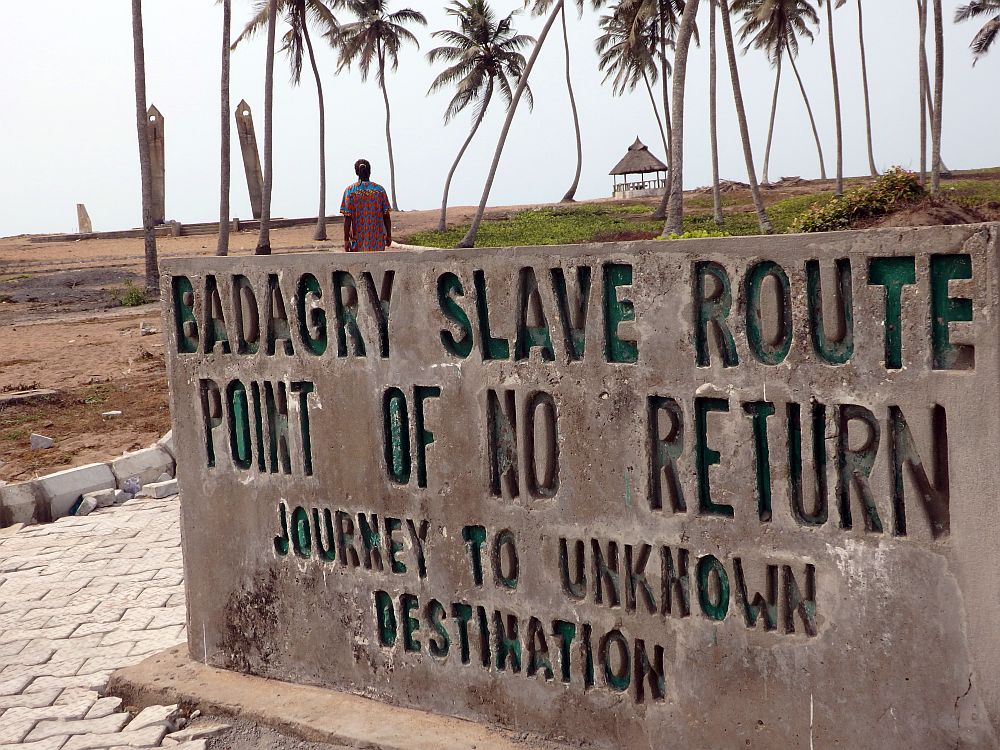

The path ends at the “Point of No Return” on a long straight beach lined with tall coconut palms. The slave traders loaded the captives onto small boats again to reach the ocean-crossing ship moored off the beach.

Once on board, packed into the belly of the ship, they would endure the “Middle Passage” to the Americas, which could take as much as three months. If they survived – and many didn’t – they would be put to work on a plantation in the Caribbean, Central or South America, or the United States.

You might also be interested in Livingstonia: A glimpse of Malawi’s colonial past.

A memorial, a beach and tourism in Badagry

The history of this place is shameful and heart-breaking. In any form it would be difficult to convey the magnitude of suffering caused by the slave trade for 400 years. Unfortunately, the Point of No Return doesn’t manage to express its significance clearly enough.

A memorial marks the spot where the slaves finished their walk across the island, though it does not appear as originally intended. The intention was that the two vertical pieces, leaning inwards, represent a man and a woman chained together, but the salt water has caused the chain to disintegrate and fall off the monument.

That disintegration is indicative of the state of the place as a whole: neglected. Between the memorial and the beach, for example, someone made a start at building a larger, better memorial, but it appears to have been abandoned, leaving only the foundation.

Note added April 23, 2025: Judging from some photos I found online, a new structure was added to the two remaining vertical pieces of the original monument. They now frame the entrance to a tunnel that rises and curls around and over itself, ending with an opening facing the sea. It is called the Ark of Embarkation. I presume the idea is to represent the darkness of those last steps into a dark, unknown future. However, construction seems to have been abandoned and it is closed.

Putting aside the history of the place, the beach itself should have enormous potential for tourism. On the day we visited, it was completely empty as far as I could see in both directions, and those coconut palms are lovely lining the beach. Yet the sheer quantity of trash strewn absolutely everywhere was disheartening.

Set back behind the line of palm trees to one side of the wide path are the hulks of several small vacation homes. I say “hulks” because the houses have stood unfinished for four years, according to our guide.

The same goes for the path itself. A scheme at some point in the past intended to make the memorial accessible also for the disabled or elderly, which would require a better surface than the deep sand we walked through. Only about the last one or two hundred meters has actually been paved with bricks.

Book your accommodations in Lagos.

Many people, nevertheless, do visit the place: mostly Nigerians visiting their own history, and often school groups too. If the local government is ever going to get foreign tourists to come here, though, they’ll have to invest considerable funds to make it accessible and worth the trip. (And that’s putting aside all the other reasons foreigners don’t visit Nigeria: corruption; crime; inflation; and their fear of Boko Haram, despite the conflict’s distance from Lagos.)

To explore the transatlantic slave trade in West Africa in more detail, consider this 9-day/8-night tour. It includes sites related to the slave trade in Nigeria, Benin, Togo and Ghana.

Other things to see in Badagry

A few other sites in Badagry are worth visiting, though we could only see exteriors because we visited on a Sunday. The “First Storey House”, dating to 1845, was a missionary’s home. It was the first building in the country to have more than one story. Owned by the Anglican Church of Nigeria, it is open for visitors.

First Storey House: Marina Road, marked on Google as “Badagry Building.” Open Monday-Saturday 9:00-17:00, closed on Sunday.

The Badragry Black Heritage Museum, in a beautiful 1863 colonial-era building, originally a district office, serves as a more general slave trade museum. It houses more information on the slave trade and the rest of the history of the people of Badagry. We also peeked over the wall into the missionaries’ cemetery; it is as neglected-looking as the Point of No Return.

The Badagry Black Heritage Museum: On Marina Road just down the street from the First Storey Building. Open Monday-Saturday 9:00-17:00. Closed on Sunday.

A trip to Badagry, Nigeria

I think it’s safe to say that Badagry is very off-the-beaten-path, at least for tourists. Given its minimal level of development for tourism, I certainly wouldn’t recommend going out of your way to see it. The still-standing slave forts of Ghana would be a more natural choice to explore the history of the slave trade.

However, if you are going to be in Lagos anyway, as I was, it’s worth a visit, both for the adventure of driving there (see my post about driving in Lagos) and for exploring Badagry’s remaining slave trade relics.

Getting there

I can’t give much advice on how to get there; the school where I led a workshop provided me with a car, a driver and a security guard. I’d suggest doing the same: get a car and driver and take local advice about whether the security guard is actually necessary. Taxis are available; ask at your hotel. There is also public transportation of a sort; I saw plenty of small vans on the road. I have no idea, though, how you’d get from central Lagos out to Badagry with them.

The easiest way to see it would be to take a day tour like this one. It includes pick-up from your hotel in Lagos.

The drive took us more than two hours in each direction, so I’d suggest putting aside a whole day for the trip from central Lagos. Google shows it, as I check now, midday on a Monday, as 66 kilometers (41 miles) from central Lagos, taking 2 hours and 42 minutes.

Have you been to Badagry recently? If so, please add a comment below! I’d love to know, for example, if the new structure at the beach has been completed. Has the pavement of the path progressed at all? Is the beach any tidier?

My travel recommendations

Planning travel

- Skyscanner is where I always start my flight searches.

- Booking.com is the company I use most for finding accommodations. If you prefer, Expedia offers more or less the same.

- Discover Cars offers an easy way to compare prices from all of the major car-rental companies in one place.

- Use Viator or GetYourGuide to find walking tours, day tours, airport pickups, city cards, tickets and whatever else you need at your destination.

- Bookmundi is great when you’re looking for a longer tour of a few days to a few weeks, private or with a group, pretty much anywhere in the world. Lots of different tour companies list their tours here, so you can comparison shop.

- GetTransfer is the place to book your airport-to-hotel transfers (and vice-versa). It’s so reassuring to have this all set up and paid for ahead of time, rather than having to make decisions after a long, tiring flight!

- Buy a GoCity Pass when you’re planning to do a lot of sightseeing on a city trip. It can save you a lot on admissions to museums and other attractions in big cities like New York and Amsterdam.

- Ferryhopper is a convenient way to book ferries ahead of time. They cover ferry bookings in 33 different countries at last count.

Other travel-related items

- It’s really awkward to have to rely on WIFI when you travel overseas. I’ve tried several e-sim cards, and GigSky’s e-sim was the one that was easiest to activate and use. You buy it through their app and activate it when you need it. Use the code RACHEL10 to get a 10% discount!

- Another option I just recently tried for the first time is a portable wifi modem by WifiCandy. It supports up to 8 devices and you just carry it along in your pocket or bag! If you’re traveling with a family or group, it might end up cheaper to use than an e-sim. Use the code RACHELSRUMINATIONS for a 10% discount.

- I’m a fan of SCOTTeVEST’s jackets and vests because when I wear one, I don’t have to carry a handbag. I feel like all my stuff is safer when I travel because it’s in inside pockets close to my body.

- I use ExpressVPN on my phone and laptop when I travel. It keeps me safe from hackers when I use public or hotel wifi.

You REALLY went off the beaten path! And these pictures give me goosebumps…

Me too!

Here in the other Lagos (Portugal) is the Slave Market Museum, built in the 15th century and the first slave market in Europe to sell the unfortunates captured and transported from Africa. We’ve visited other museums as we’ve traveled to try and understand its impact upon the countries who imported them and the slave’s descendants in places as disparate as Curacao, The Corn Islands in Nicaragua, Guatemala and the Dominican Republic. Your post illustrates well the full horror and disturbing facts of the trade.

One forgets how far-reaching the slave trade was. Millions taken captive and shipped across the ocean. Communities destroyed in Africa because of their kidnapped population. Whole societies in the New World dependent on slavery for their prosperity. Prosperity in Europe based on the slave trade (those Golden Age Amsterdam buildings I’ve written about, for example). And so on.

Yes I’m a little depressed reading about this, although the history is quite fascinating and to see that other African people did this to each other.

It’s not just history, for two reasons. First of all the extent of its effects are visible to this day in Africa and the Americas. Second, slavery in various forms still exists today in some parts of the world.

What a heart-breaking place – yet a beautiful beach – minus the rubbish of course. Do you think the rubbish gets washed up onto the beach?

Yes, I suppose so.

Rachel, your post taught me certain things and reminded me others. I think the worst part of this is remembering that the slave trade was carried mainly by Africans. In modern times, I have observed how one race damages the people of their own race. Seems like they have not learned anything from history.

It was carried out by Africans, but wouldn’t have grown as huge as it did without the insatiable demand from the European traders. Apparently the slavery that was practiced in Africa originally was considerably more benign and much smaller scale. People didn’t carry out raids in order to collect slaves. Rather, prisoners taken in conflicts over other issues became slaves, and it wasn’t hereditary slavery either.

So interesting! One hardly sees blog posts, or any articles, on Nigeria. It’s on my wish list.

Hi Rachel! Interesting post, Nigeria is not on my list to visit. That being said, I would probably want to this. Did you know that there is a slave museum in Lagos in Portugal’s Algarve? It wasn’t open when I was there this winter. Definitely on my list to see next time. Thanks for hosting this week! #TPThursday

I travelled to Badagry in my teens but didn’t visit this part. My parents used to buy fresh fish in bulk when life was much more pleasant living there.

It’s such a shame Badagry isn’t being used as a tourist hotspot. There is so much potential there. The history about the slave trade just makes my stomach churn! Thanks for sharing.

There’s definitely potential there: a postcard-worthy beach (if it was cleaned up) and a really moving history. They’d have to do something about the traffic though. It’s really awful.

Thanks for this detailed review, Slavery was real and sadly after so many years after its abolishment it still exists even in corporate settings

Ce lieu me rappelle ma dernière visite des sites touristiques de Ouidah au Sud du Bénin. On revis à travers tous ces lieux le drame indescriptible qu’ont vécu certains de nos ancêtres. Il est tant que nous nous orientons vers un nouvel horizon.

Translation for other readers: “This place reminds me of my last visit to the tourist sites of Ouidah in the South of Benin. Through all these places, we relive the indescribable drama that some of our ancestors experienced. It has been so long that we are moving towards a new horizon.”

Rachel, thanks for the excellent write up. I visited Badagry during my last stint in Nigeria. I have worked and lived there through a couple of different military juntas and last under the democratic rule from 2009 to 2014. Unlike you, our group went via boat which made the journey much faster.

I have tried to impress on people of all races and in case of Nigerian friends and colleagues the importance of this visit in order to grasp the inhumanity of humans. Although other trips in Nigeria taken with the Nigerian Cultural society were more enjoyable like those to the Durban in Kano and Katsina, none were as powerful as the visit to Badagry. I have also traveled in, worked and lived for years in Angola, Republic of Congo, DRC (Zaire), South Africa, Zambia, Botswana, and Tanzania.

When one loosely debates the “original sin” of slavery with colleagues, family, and friends they can’t grasp how far back and who is implicated in said “Sin”.

Best Regards… JJP

Thanks, I will be forwarding your link to friends who are educators.

Thank you for the kind words! Yes, it’s more complicated than usually presented, but it’s important not to accept “whataboutism”, i.e. the argument that some Africans traded blacks as well as whites, that Africans owned slaves, etc. That’s true, but doesn’t excuse anything: how whites continued to oppress and enslave black and indigenous people for hundreds of years. As for Badagry, it’s really not ready for prime time, i.e. the numbers of visitors who would and should visit it. The infrastructure just isn’t there. I’d suggest Ghana instead, where places like Elmina Castle illustrate the same or similar history but are better able to handle tourism.