Ruminations on an Auschwitz Tour

When I was a kid – six or seven years old, I’d guess – my parents decided I was old enough to see a documentary about the Holocaust. With no idea what it was about, I was delighted to be allowed to stay up past my bedtime.

If my parents explained it at all, before or after, I don’t remember. I do remember how I felt, downstairs in the basement den, sitting on our old couch with my sisters: the same horror that anyone feels seeing these old films from before the Nazis built the gas chambers, when skeletal remains were thrown into huge ditches by people who were equally skeletal.

The difference for me, I think, was that I had no idea how to digest the images. The horror sat in the pit of my stomach: a heavy green lump. It’s been there ever since.

Disclosures: I received this trip to Auschwitz for free as part of an influencer conference. This has no effect on my views about the tour. Also, this article contains affiliate links. Making a purchase through an affiliate link will mean a small commission for this website. This will not affect your price.

My parents were never particularly good at talking about feelings, and as far as I remember I was simply sent to bed after the documentary. I don’t remember them giving any explanation, either before or after, but they must have, since I had a vague idea that a bad man named Hitler had killed lots and lots of Jews.

I didn’t even cry; I was old enough to think that crying is for babies, but too young to understand that everyone cries sometimes. I just went to bed without complaint, and fell asleep quickly, sleeping undisturbed.

But the green lump stayed. Undigested. Unprocessed.

I ignore the heavy green lump most of the time and get on with my life, but it’s always lurking, primed to pounce, and I’m startled how easily it surfaces whenever the subject of the Holocaust comes up.

I can place the images in context now, which, of course, doesn’t make it any better. German soldiers made these films as a souvenir: something they were proud of.

I understand now that those skeletal people, dumped as if they were garbage, were my people: Jews like me. People hated me that much. As a child, that was so outside my ordinary day-to-day life in suburban Connecticut that I just couldn’t connect it with this world I lived in.

I tell this story because I recently went on a tour of Auschwitz concentration camp in Poland. In this place, Nazis turned genocide into an industrial enterprise, efficiently processing, in just a few years, over a million souls into ashes.

Bearing witness

I believe it is important to bear witness. These crimes must not be forgotten, no matter how painful it is to think about them. This is why I visit Jewish museums, synagogues, and Holocaust memorials on my travels. I’ve also visited other scenes of historical cruelty, such as Badagry, Nigeria, where so many Africans were packed onto boats to be taken to lives of slavery, Hiroshima, Japan, the site where an atomic bomb destroyed an entire city of civilians, and the KGB Museum in Riga, Latvia, where prisoners were tortured and executed for opposing Soviet rule.

As a Jew, though, and especially in recent years, with a noticeable rise in anti-semitism in Europe, I feel an urgency about bearing witness to the Holocaust.

But I didn’t want to tour Auschwitz. I felt like I already knew the story, and knew it too well. I – and every Jew today – carry it with us, even when, like me, we have not been touched directly by the Holocaust. So do Roma and Sinti people, homosexuals, the disabled, and any other group that the Nazis would have rated as undeserving of life.

My friend Roz is the one who changed my mind. She pointed out how moved she was, on her tour of Auschwitz, by the strength of the human spirit:

The fact that amongst the living hell, inmates still took the opportunity to celebrate birthdays, religious festivals and anniversaries. This happened in the latrines where the soldiers wouldn’t go.

She added:

I think it’s important for us to go to understand the scale of the atrocities, to value our freedom and to ensure that such a thing never happens again. Also to understand how quickly life can change if we don’t act.

So I signed up to take the tour, offered free to bloggers at a conference in Krakow. But it was largely out of a sense of obligation: to bear witness.

In the days leading up to the Auschwitz tour, I dreaded it. I didn’t want to be confronted with all of that horror again. I feared I’d burst into tears in public; I fought back tears often in the days before my tour. The green lump in my stomach awoke and felt eager to emerge.

At the same time, I was afraid of other tourists’ disrespect: the kind I saw at the Memorial to the Murdered Jews in Berlin. If I heard schoolkids laugh, what would I do? Make a scene? Would I be able to keep the lump down and stay calm?

You might also be interested in the following articles:

Tour of Auschwitz

A small group of bloggers and Instagrammers, we were picked up by our van early in the morning for the hour and a half ride. Resigned, passive, I went along. It felt necessary. I tried to shut my brain down, think about other things.

On the way in the van, they showed a documentary about Auschwitz and its sister camp, Birkenau. Some of the bloggers slept; others watched. To avoid tears, I looked away often, letting my eyes wander between the screen and the peaceful country scenery passing by out the window. Brilliant green springtime fields, sleepy farmhouses. It was hard to believe that the scenes on the screen happened here.

Arriving at the first part of the Auschwitz complex, called Auschwitz I, now used as the primary Auschwitz museum, our driver handed us over to a guide employed by the Auschwitz museum, named Lukasz. We all wore headphones so that he could talk quietly into a microphone and still be heard. Giving a tour this way keeps everyone respectfully quiet: the guides don’t have to speak loudly and the visitors keep quiet in order to hear the guides. So equipped, we moved through Auschwitz in near silence.

Auschwitz I

It’s pretty here.

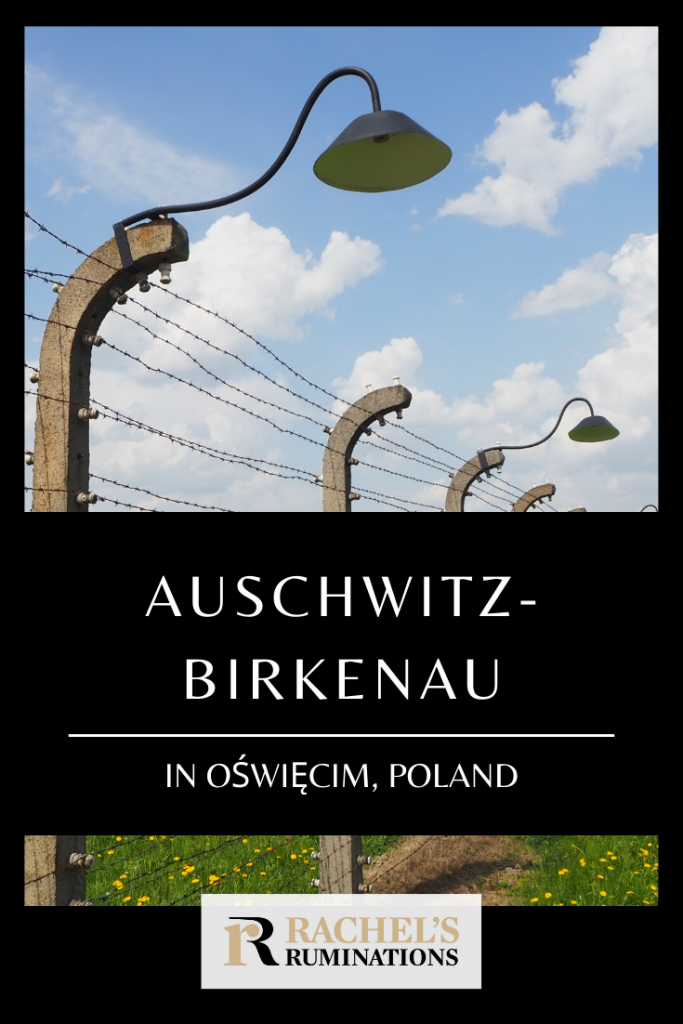

I flushed guiltily when I caught myself thinking it. But it was. The barracks are simple brick structures set in neat rows, and on my visit in early May, the trees among them stood bright with the green of springtime growth. Flowering bushes guarded some of the entrances. The only thing that gave away their true purpose was the tidy fencing of barbed wire.

Auschwitz I was the first camp, built around 22 already-established army barracks in the Polish village of Oświęcim. Starting in 1940, it was used as an internment camp for various Russian and Polish political prisoners and criminals. In 1942 it became a concentration camp, meant to work mainly Jews, along with homosexuals, political prisoners and Roma/Sinti, to their deaths, and, soon after, to serve in their efficient extermination in the gas chambers.

Passing under the cynical “Arbeit Macht Frei” (Work sets you free) gateway that greeted the doomed deportees, our guide led us into several of the barracks buildings, one at a time. Some showed general information about what happened at Auschwitz, with photographs, explanatory signs, maps, examples of Nazi documents and a single urn of ashes meant to memorialize all the victims. We didn’t see all the exhibits on this tour. We missed, for example, one barrack devoted to the story of the Roma and Sinti who died there.

Having crossed the threshold and begun, the heavy green lump lurking in my gut threatened to escape, but I kept trudging along among the hordes of tourists.

Material Proofs of Crimes

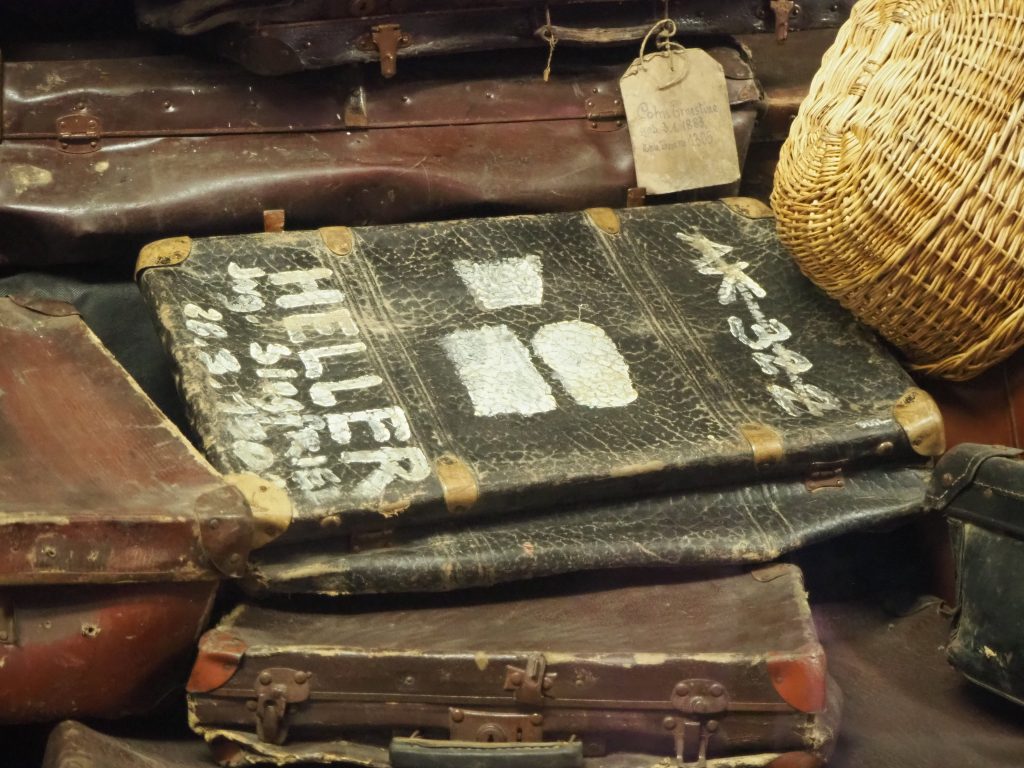

The hardest exhibit to view, for me and probably for everyone who tours Auschwitz, is called “Material Proofs of Crimes.” It shows ordinary items of everyday life, found at the camp after its liberation.

A massive pile of eyeglasses.

A much bigger pile of human hair, much of it neatly braided. I tried not to think of the ordinariness of that: We’re getting transferred to a camp until the war is over. I’ll braid my hair so it stays neat on the train. The hair was used to make cloth, and we saw a sample of that too.

An equally large pile of shoes. Again, I fought to keep the green lump down. Some of these shoes were 1940s stylish: wedge heels, colorful straps. I pictured people trying on shoes in a shop, eying their feet in a mirror, making a choice.

A long case of prosthetics: things like fake limbs and crutches and braces.

An entire roomful of discarded metal bowls and pots. These were used in the camp by those who weren’t killed immediately and who provided the slave labor that the Nazis needed for their extermination machine.

That heavy green lump finally escaped at the long display case filled with a haphazard pile of luggage. People packed their most precious possessions to take with them in these battered suitcases, and some had written their names and addresses in large letters on the sides. One of them proclaimed “HELLER”. Could this have been family?

In that dense crowd of people, I was the only one crying, as far as I was aware. Noticing the ugly sounds I was making, they turned, stared, and turned quickly away again. Sobbing, but at the same time trying to hold it in and not make a spectacle of myself, I pushed my way through the crowd toward the door.

Rushing past the next few cases, I reached my group in the relatively less emotional section of the museum that showed the living quarters of the prisoners. Here I started taking pictures again, focusing on how to use my camera to pull myself together; figuring out the best way to set it, using it as a screen between the horrors I was witnessing and me. It kept the green lump at bay.

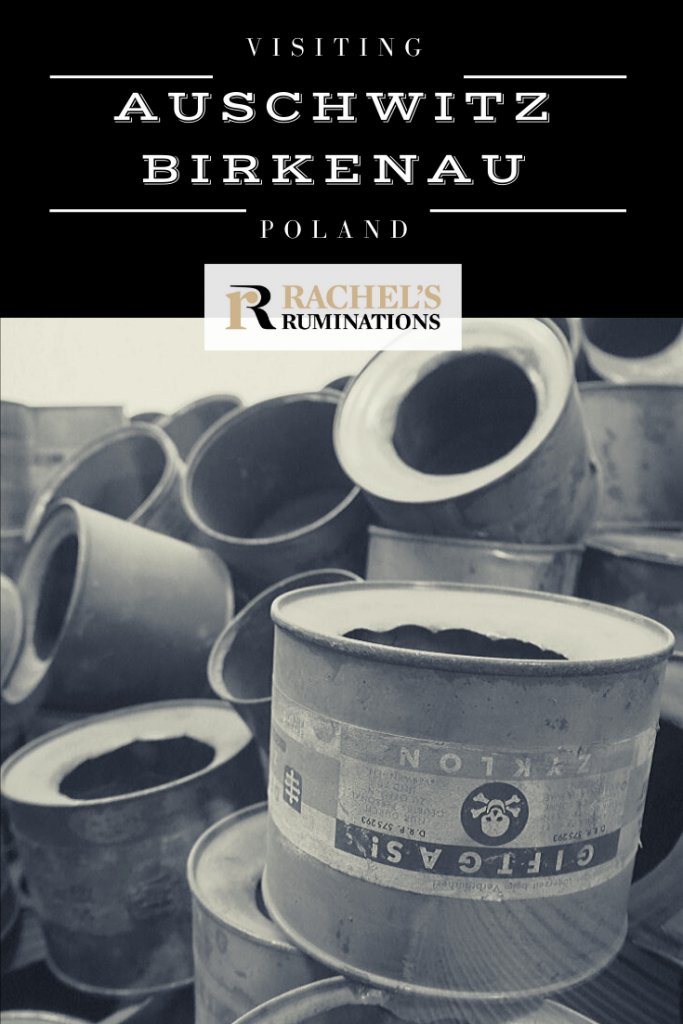

The gas chambers

Auschwitz I was where the Nazi scientists experimented with using Zyclon-B to kill inmates. The large-scale exterminations happened at Auschwitz II, but the Nazis destroyed those gas chambers and incinerators toward the end of the war. For that reason, the experimental one at Auschwitz I has been preserved.

We walked through the room – not furnished with fake shower heads like the ones at Auschwitz II were – where the Zyclon-B pellets were dropped through a hatch in the roof. Here they perfected the procedure using political prisoners as their guinea pigs, figuring how much Zyclon-B it would take to kill everyone in the room within 20 minutes.

In the next room stood a few ovens for cremations. If they were going to exterminate so many people so fast, they would need to dispose of the bodies quickly as well.

Apparently, the ashes were either spread on farm fields or dumped in the river nearby. The beautiful farmland we passed on the way here had been fed by the bodies of the victims.

Auschwitz II Birkenau

Auschwitz II, also known as Birkenau, is only three kilometers away. We were herded onto the van to the entrance and met the same tour guide, Lukasz.

This camp was much bigger than Auschwitz I. It was where most of the prisoners died. The famous pictures of the train pulling in and the Nazis separating out the Jews into two lines – the strong to work as slave labor, the weak to go straight to the gas chambers – happened here.

What remains is the entrance gate, the train tracks, some intact barracks and many ruined barracks. The gas chambers and ovens are heaps of rubble. A large memorial stands nearby: an abstract concrete form in a brutalist style.

At its foot is a row of plaques, each in a different European language:

For ever let this place

be a cry of despair

And a warning to humanity,

Where the Nazis murdered

about one and a half

million

Men, women, and children,

mainly Jews

From various countries

of Europe.

We walked through an intact barrack where prisoners slept on shelves. The famous photos taken at the liberation that show the starved faces of people lying on the shelves were taken in similar barracks. Built to house 40 prisoners, it wasn’t unusual for a barrack to house 700.

The slave laborers generally only survived for a couple of months, victims of starvation, cold, and/or disease. With inmates sleeping in these packed dormitories on too little nutrition, little heating, and too much work, diseases spread quickly.

Auschwitz II, while less confrontational than Auschwitz I, with its piles of personal objects, emphasizes the enormity of the project through its sheer size: 140 hectares (346 acres or a half a square mile) with 300 barracks and buildings.

What if Holocaust deniers visit Auschwitz?

We walked through the entrance gate and along the train track to the far end of several fields of ruins of barracks. The heavy green lump inside me had receded by this time, soothed by walking and a certain numbness that had set in. I asked Lucasz what he did if people showed up on his tour who approved of “the Final Solution.”

“Well, there are really two kinds. First, the deniers. No matter what I say, they won’t be convinced. They can dismiss everything as faked. But generally they don’t say anything.”

“The second kind is the neo-Nazi. They don’t say anything either, but I can tell who they are. They smile, but try to hide it.”

I wanted to ask if he kicked them out of the museum, but we were interrupted.

At one point as we were walking, two of the other bloggers were talking. I didn’t hear what they were saying, but one of them let out a small laugh. The guide immediately told them sternly to be quiet. I was pleased not only that visitors are told to show respect, but that someone was calling them on it when they didn’t.

Problems of Auschwitz tourism

I have some issues with how the tours of Auschwitz are conducted. I’m not criticizing the van company’s conduct: their part of the tour was clear and efficient. Nor am I criticizing Lucasz, the tour guide; given the difficulties of the large crowds at Auschwitz I, he did a competent job.

I am criticizing how Auschwitz tours are organized at the Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum. The problem is the crowds. We visited on a Sunday, and Auschwitz I was ridiculously crowded. I understand that the idea is that as many people as possible should see Auschwitz: bearing witness is important, and learning about genocide should help prevent future genocides.

This was really extreme, though. I was supposed to be in a group of perhaps 15 people. The problem was that some large number of other groups were passing through the same barracks buildings at the same time.

We shuffled along in an unending stream of people. I often could only partially see the display cases because of the depth of the crowds. If I took the time to worm my way nearer, I lost sight of my group. Lukasz kept walking while I struggled to see and stay within earshot of him. His voice becoming crackly in the headphones was my signal that he’d moved one or more rooms ahead of me, so I would hurry up to avoid losing the group entirely.

This is the only picture I took of the crowd, but you can see how very few of the people had a chance to take in the photos on display. I took this picture in the hopes of being able to zoom in and read the signs later, which only worked for the nearer ones. My guide was somewhere at the far end of the room; I couldn’t pick him or the rest of my group out of this crowd.

What I fear is that this crowding detracts from the effect of the items and information on view. If people are busy worrying about keeping up, or can’t hear what their guide is saying, they may miss the essentials of the experience.

And that’s the point of visiting: to get a visceral, emotional understanding of what happened there.

The organization that runs Auschwitz needs to do two things:

- It needs to extend the exhibits across more different barracks to spread out the crowds, and

- It needs to set lower limits on the number of tickets it issues, and control the timing too, much as the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam does. Allowing groups to enter at fifteen-minute intervals would prevent the crowd from becoming overwhelming, even if they did end up bunched together by the end of a tour.

Another option would be to dictate routes through the barracks museums, in addition to timing entrances. There could be three or four different possible routes so that they wouldn’t impede each other.

Free speech and Auschwitz

I don’t feel like I can write about Auschwitz without discussing the Polish law that regulates how we speak about Auschwitz, making it illegal to accuse “the Polish Nation of participation in, or responsibility for, communist or Nazi crimes.” Passed by the nationalist Law and Justice party that has gained power in Poland, it prohibits the use of phrases like “Polish death camp.” Instead, we have to call it a “Nazi death camp.” This “crime” is punishable by up to three years in jail.

When I mentioned the new law to a Polish member of our group visiting Auschwitz, he said “Three years isn’t enough.” I dropped the subject.

This emphasis on “It wasn’t our fault!” is disingenuous. Yes, the Nazis were responsible. They conceived of and built the camps. They planned and carried out the genocide. The camps are on Polish soil but were not their creation.

However, the new law ignores the fact that, while some Poles resisted the Nazis, some either acquiesced or actively collaborated.

Take the village of Jedwabne, for example, where in 1941 Poles herded hundreds of Jews into a barn and set the barn on fire while the Nazis looked on. (See Stefan Zgliczynski’s article summarizing Poles’ complicity during the Holocaust.)

A law that does not allow us to speak of this history strikes me as pretty Nazi-like in itself.

Anti-semitism in post-war Poland

This denial of complicity is also happening in a country that even carried out “anti-Zionist” campaigns in the Communist era after the war, when few Jews remained in Poland. As a history major at Yale, I studied this period of Polish history. Immediately after the war, in the general anarchy of the Soviet takeover, many remaining or returning Jews were killed in individual attacks or pogroms. Sometimes this was due to anti-Communist feeling, conflated with the fact that some Jews from Russia settled in Poland after the war. Sometimes it was due to “blood libel,” the belief that Jews kidnapped Christian children in order to use their blood in rituals. The most famous of these pogroms based on blood libel happened in 1946 in Kielce, and frightened the remnants of Poland’s Jewish community enough that many left the country.

Later, the Soviet-controlled Polish government suppressed any rebirth of the Jewish community. In 1967, when Israel won the Arab-Israeli War, a series of show trials and dismissals of Jewish officials and the discovery of a supposed Zionist plot to take power was essentially a side effect of a power struggle within the government. (Reference: Anti-Semitism and Anti-Zionism in Historical Perspective).

When the 1968 student anti-government demonstrations in Warsaw broke out, a rise in nationalist feeling much like what is going on today in Poland scapegoated the Jewish community through an “anti-Zionist” campaign. Jews working in government, Jewish teachers, students and their parents, were ousted from their jobs. The purge spread to the army, the government and the Communist Party. This led about half of the remaining 30,000 Polish Jews to leave the country.

Note: I’m not saying that how Poles have addressed their own wartime history is particularly worse than in other countries. Many other European countries honor their World War II resistance fighters while conveniently ignoring their collaborators.

The difference here is that Poland now has a law forbidding people to speak about complicity. I fear the slippery slope, and what other statements will become illegal.

Auschwitz tour guides

More controversy has broken out in Poland about the tour guides at Auschwitz. Nationalists criticize the use of tour guides who are not Polish, even to the extent of a vandalism attack on the house of an Italian guide. The Nationalists fear that the non-Jewish Poles who died at Auschwitz will be left out of the story.

I can categorically state that this is not true.

The museum exhibits report quite clearly that 1,100,000 Jews were killed, 140-150,000 Poles, 23,000 Roma, 15,000 prisoners of war from the Soviet Union, and 25,000 others. Our tour guide particularly told the story of the earliest people interned and killed there: Polish prisoners of war. The Nazis, in the first years of the camp, photographed their prisoners, and one of the barracks is lined with these stark photos, mostly non-Jewish Poles.

Given that so many more Jews were killed there (90-95% of those killed at Auschwitz-Birkenau were Jews), it makes sense that they would get more attention in recounting the story, but the non-Jewish Poles are certainly not ignored.

While I feared a biased approach, given my general knowledge of anti-Semitism in Poland, what I heard was a balanced, respectful, factual recounting. Kudos to the museum and to Lucasz for keeping their integrity in the face of sometimes violent nationalistic pressure.

Visiting Auschwitz-Birkenau

You can visit Auschwitz-Birkenau individually or with a group. If you go as an individual, reserve a ticket for free at visit.auschwitz.org. You can join a group tour on-site, or else explore it on your own. They are no longer giving tickets to individuals who just show up; you must book on their website ahead of time. The tours are offered in English, Polish, French, German, Russian, Spanish and Italian.

To get there without a tour, either drive or take a train or bus. Driving from Krakow takes about an hour and a quarter. You can take a bus or a train from the Central train station in Krakow to Oświęcim, which should take a bit more than two hours. From Oświęcim either walk the two kilometers to the camp or take a local bus. You’ll then need to walk the three kilometers from Auschwitz I to Auschwitz II Birkenau, or else take the museum’s shuttle bus.

The easiest way to get to Auschwitz is with a tour. Many companies offer Auschwitz tours from Krakow and other cities. They arrange the entrance tickets for you, and they drive you from Auschwitz I to Birkenau. You might get other individual tourists added to your group when you arrive, since the museum arranges the tours inside the camp, not the tour company.

I might have preferred to visit Auschwitz on my own. It would have allowed me to take my time, absorbing the museum at my own speed. I would have been able to take breaks, standing outside, surrounded by the springtime green, escaping the pressure of the crowds for a few moments. On the other hand, perhaps it was good that I was rushed along. It muted the effect of the horrible things I was seeing, or rather shortened my exposure. It allowed me, most of the time, to keep the heavy green lump contained. Make your own judgment about which would be better for you.

Hours vary depending on time of year. It opens at 7:30 every day except for January 1, December 25 and Easter Sunday, when it’s closed. In the summer it’s open until 19:00, but at other times of year it closes earlier. Check the museum’s website for information.

Some advice for your tour of Auschwitz:

- Bring tissues.

- Only carry a small bag. They won’t let you take bigger bags in.

- No food, no cigarettes. A bottle of water is okay.

- Wear good walking shoes. Especially at Birkenau, you’ll walk a lot.

- If it’s likely to be good weather, put on sunscreen. Much of the walking at Birkenau is outside.

- Follow instructions in terms of where you may or may not take pictures. Sneaking pictures is disrespectful. So are selfies.

- Don’t take children under 14.

- Dress decently, not showing too much skin. Again, it’s disrespectful.

- Keep your voice down.

- Visiting will take most of the day. Don’t plan anything big for after the tour. You won’t feel like doing much.

- Some tours combine Auschwitz with a visit to Wieliczka salt mine. Don’t do it! The salt mine is fun, but it just seems disrespectful to combine fun with touring a concentration camp.

If you found this article interesting, please share it. The image below is formatted for Pinterest.

My travel recommendations

Planning travel

- Skyscanner is where I always start my flight searches.

- Booking.com is the company I use most for finding accommodations. If you prefer, Expedia offers more or less the same.

- Discover Cars offers an easy way to compare prices from all of the major car-rental companies in one place.

- Use Viator or GetYourGuide to find walking tours, day tours, airport pickups, city cards, tickets and whatever else you need at your destination.

- Bookmundi is great when you’re looking for a longer tour of a few days to a few weeks, private or with a group, pretty much anywhere in the world. Lots of different tour companies list their tours here, so you can comparison shop.

- GetTransfer is the place to book your airport-to-hotel transfers (and vice-versa). It’s so reassuring to have this all set up and paid for ahead of time, rather than having to make decisions after a long, tiring flight!

- Buy a GoCity Pass when you’re planning to do a lot of sightseeing on a city trip. It can save you a lot on admissions to museums and other attractions in big cities like New York and Amsterdam.

- Ferryhopper is a convenient way to book ferries ahead of time. They cover ferry bookings in 33 different countries at last count.

Other travel-related items

- It’s really awkward to have to rely on WIFI when you travel overseas. I’ve tried several e-sim cards, and GigSky’s e-sim was the one that was easiest to activate and use. You buy it through their app and activate it when you need it. Use the code RACHEL10 to get a 10% discount!

- Another option I just recently tried for the first time is a portable wifi modem by WifiCandy. It supports up to 8 devices and you just carry it along in your pocket or bag! If you’re traveling with a family or group, it might end up cheaper to use than an e-sim. Use the code RACHELSRUMINATIONS for a 10% discount.

- I’m a fan of SCOTTeVEST’s jackets and vests because when I wear one, I don’t have to carry a handbag. I feel like all my stuff is safer when I travel because it’s in inside pockets close to my body.

- I use ExpressVPN on my phone and laptop when I travel. It keeps me safe from hackers when I use public or hotel wifi.

Thanks for being brave enough to share your personal feelings on such a sensitive topic. My family had fortunately already come to America prior to the extermination campaign. Visiting Auschwitz would be a difficult activity for most people, but you handled the subject quite professionally.

Yes, my family went to the US after earlier pogroms at the turn of the century. But they lost touch with any remaining family, so I don’t know more than that. Thanks for reading!

First a comment on bloggers who sleep through films and are able to laugh at whatever when at such a site . . .those folks are the ones who will forever keep the blogosphere from being taken seriously as a means of information and writing. As for your tour: I’ve visited the Holocaust Museum in Washington DC on nearly every trip I’ve made to that city. Not because I enjoy it, but because I believe everyone should visit that museum. And I too, even though I am not Jewish, have teared up and had to do some ‘ceiling staring’ along the way. . .mankind’s inhumanity to mankind is rather hard to take. A beautifully written post, Rachel.

The sleeping didn’t bother me; it was early and we were all tired. And the laughing I didn’t even hear, since I’d moved away to take a picture. I just heard the guide’s response. But I get your point: there’s a lot of mindless gushing and ignorance of context in the blogosphere. I haven’t been back to Washington since that museum was built but I’ve heard it’s excellent. I’d recommend Yad Vashem if you’re ever in Israel. Thanks for visiting!

I chose to read Part 1 because I want to feel what the writer is feeling. And you shared it with us so well. Auschwitz cannot be visited without evoking the kind of emotion that will make sure such a horrific crime will not be repeated.

Growing up I always felt uneasy when it came to anything about the Holocaust. I never watched Shindler’s List. I never knew why until I was in my 40’s and discovered that my biological father was Jewish. I don’t think I will ever visit the concentration camps, but I never say never. I visited the Killing Fields in Cambodia and that was horrific. Visiting a place where relatives could have been gassed would be extremely difficult. I can understand why it was so difficult for you to go there.

Through high school and college, I read everything I could about the Holocaust, but after I had my first child, I became incapable of forcing myself to do so. I had to send my sister to our sons’ Sunday school when a parent was required to attend the day they showed Schindler’s List. So, I don’t know if I’d have the courage to “visit” Auschwitz or Birkenau. I haven’t visited the Holocaust Museum in D.C. nor Yad Vashem in Israel. When we visited Budapest a few years ago, we toured a restored synagogue. Our volunteer guide told us he lived in Tel Aviv and New York. I asked him if he ever considered moving back to Hungary after the fall of the Iron Curtain. He said, he’d never move back. He told us that on this visit, the first taxi he got into had a sign “No Jews Allowed”. It’s not just Europe where the inhuman side of human beings surfaces. It’s all over the world. I despair. I know we have “better angels”, but the evil that still lurks in the heart of humankind is staggering.

Yes, and it frightens me how easily those “better angels” can nevertheless be led to do evil, or at least to allow it to happen. You might want to read the second part of this post as well, since it addresses some of this, specific to Poland.

You are so right. Everyone should bear witness to the horrors and atrocities so many have endured throughout history. My son, who is 33, still talks about meeting a Holocaust survivor at the Holocaust museum in Detroit when he was 5-years-old. Your parents did right by you and your sisters to introduce you to a reality so many would rather forget — or as you say, deny it ever happened. Thank you.

Hearing a story from a Holocaust survivor (which I did too, as part of Sunday School, years later), is a valuable experience, even for a 5-year-old. But seeing those images at that age? I was too young. I think it would have been better to tell me about it at that age, but not let me see the photos till I was older.

Hi Rachel. I can only imagine how painful that visit to Auschwitz was for you. I found the Holocaust gallery at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights in Winnipeg to be more than I could bear.

Hi Rachel, impressive story! I think on the suitcase it might say: ing Siegfried Heller.

Thanks, Peter. Yes, I think that’s what it says. But I haven’t been able to trace him.

And……………….What about GAZA???????

What about Gaza? You sign this as Benjamin Netanyahu, but somehow I doubt he uses a yahoo email address. I can guess two things you might mean by this. One would be that you are condemning Hamas for their attack on November 7, which in its indiscriminate killing brought up a lot of feelings around the Jews’ generational trauma of the Holocaust. On the other hand, you might be saying that Israel is committing similar atrocities in Gaza right now (which is not what Netanyahu would say). Yes, that is also indiscriminate killing, and there’s no excuse for what the Likud government is doing. Lest you are thinking it is Israel’s fault as a whole, it’s not. Huge numbers of Israeli citizens are protesting daily, calling for a two-state solution and for Netanyahu to step down. And if you think that what they’re doing in Gaza somehow excuses the Holocaust, it doesn’t. They’re both wrong.

“Many other European countries honor their World War II resistance fighters while conveniently ignoring their collaborators.

The difference here is that Poland now has a law forbidding people to speak about complicity. I fear the slippery slope, and what other statements will become illegal”.

This is a lie. There is no such law in Poland. The truth is that such a law only existed for a few months in 2018 and was ultimately repealed by parliament. This is why this fragment of the text is misleading.

I just looked it up and as far as I can tell, the law, called “Amendment to the Act on the Institute of National Remembrance” is still on the books but it was indeed amended (not repealed) shortly after it was passed. It was amended to remove possible criminal penalties, but people who speak about complicity can still be tried in civil courts. (And a section about Ukrainian nationalists was also removed.)