Villa Tugendhat UNESCO site in Brno, Czechia

A few years ago I tried to visit the Villa Tugendhat UNESCO site in Brno, Czechia. It’s just a house, I thought. The architecture sounds interesting, so I’ll just stop by and see it. Then I can add it to my article on UNESCO sites in Czechia.

Well, I was wrong to take it for granted that I’d be able to see the house: I couldn’t get a ticket. Apparently the tours of the Villa Tugendhat interior – you can only see it on a tour – sell out months ahead. I had to settle for admission to the garden, and peered into the windows as best I could.

I returned to Brno again recently for the Traverse conference. Having already seen the main sights of Brno, I’d placed Villa Tugendhat at the top of my must-see list. Fortunately, it was one of the options that Brno Tourism Board offered for conference attendees, so finally I got to see the interior properly.

Disclosure: I did not pay for my visit to Tugendhat Villa; I saw it as part of a Traverse conference I attended in Brno.

Another disclosure: This article contains affiliate links. If you click on one and spend money, I will receive a small commission.

The Tugendhat family

The Löw-Beer family in Brno was very wealthy. When Grete Löw-Beer married Fritz Tugendhat, her father, Alfred, gave the couple a piece of land next to his own villa. He also offered to pay for building a house there for them. According to our tour guide, he set no price limit.

Grete took him at his word and hired Ludwig Mies van der Rohe to design the house. The costs ended up astronomical because Grete essentially gave the architect carte blanche to realize his concept for the design.

The villa was built in 1929-30, and the Tugendhats moved in in 1930. They lived there with their three children only until 1938, when they had to flee the country – they were Jews and the war was approaching.

Functionalist design

Functionalism – sometimes also called Bauhaus – is a type of modern architecture from the interwar period emphasizing function over form. The idea is that the form that results from focusing on the building’s purpose is beautiful in and of itself. In other words, the clean, clear, unadorned lines of a factory, for example, are beautiful because of their functional form. Functionalist architecture generally uses industrial materials and lots of free-flowing spaces open to the outdoors.

Mies van der Rohe

By the time the Tugendhats hired Ludwig Mies van der Rohe for their villa, he was well known as a former director of the Bauhaus school in Germany. Bauhaus was an art school focusing on design and including architecture, typography, art, interior design, and crafts. The school only lasted from its founding in 1919 until it closed in 1933 with the rise of Nazism. The staff of the school emigrated to other countries and continued to have an enormous influence in the various fields of design to this day.

Tugendhat Villa since the war

The villa served other purposes once the Tugendhats moved out. The German Reich took it over, and then after the war it housed a dance school. In the 1950s it became a government physiotherapy center. It wasn’t designated as a monument until 1963. It was in pretty bad shape, and restoration work didn’t happen until the 1980s.

The villa became a UNESCO site in 2001, after which it could be properly restored to its exact appearance when the Tugendhats lived there. The reconstruction was carried out in 2010-12. Starting during the war, much of the interior furniture had been stolen for use elsewhere. Most of the furniture we see today is replicas, but the pieces of the signature walls – more on them later – were reclaimed and restored.

Book your accommodations in Brno here.

Tugendhat Villa today

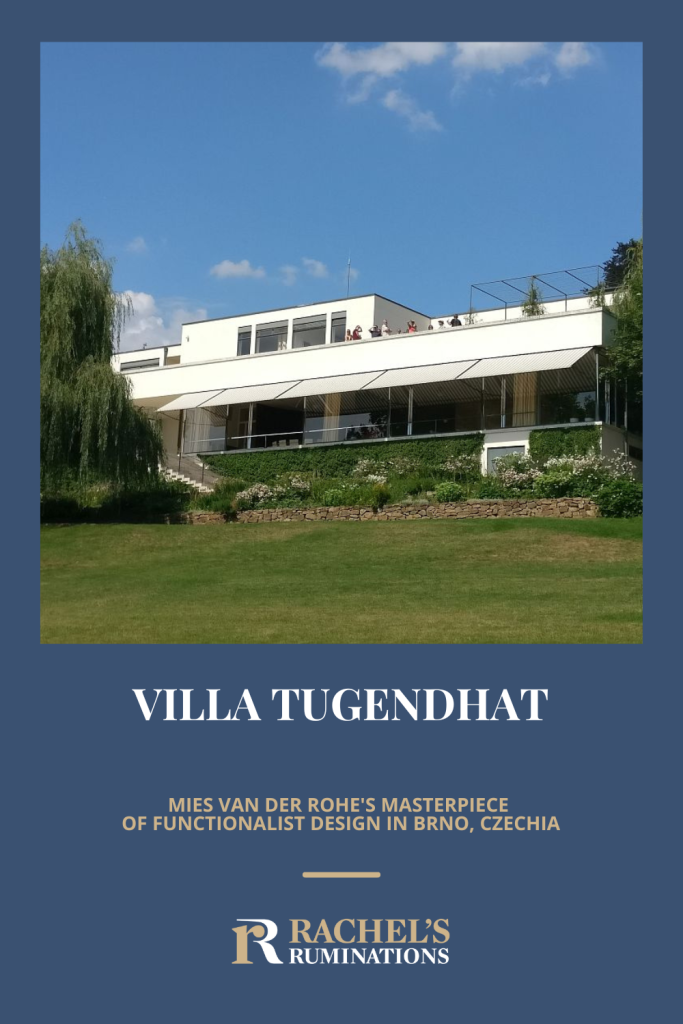

From the street, the house isn’t something you’d even notice: it’s just a single story blockish structure in white concrete. The lot slopes down from the street, so there’s much more to the house that is invisible to the street.

One of Mies van der Rohe’s important innovations in designing this house is that it is supported on a series of steel columns, each in a cross shape. In the living spaces, these columns are covered in shiny chrome. What’s important about this construction, though, is that it allows the spaces to be huge and open and to flow into each other. The exterior walls can include massive windows, since they don’t need to support the weight of the structure.

The result is a beautiful free-flowing space: dining room, living room, library, and work spaces all connected. What’s more, they connect to the outside because of those huge windows looking out on the garden. Mies van de Rohe took this even further – remember the carte blanche that Grete gave him – and created a mechanism like car windows: the huge windows could be rolled down into the level below with the aid of machinery in the basement. That meant the space was literally part of the outdoors.

Architecture as art

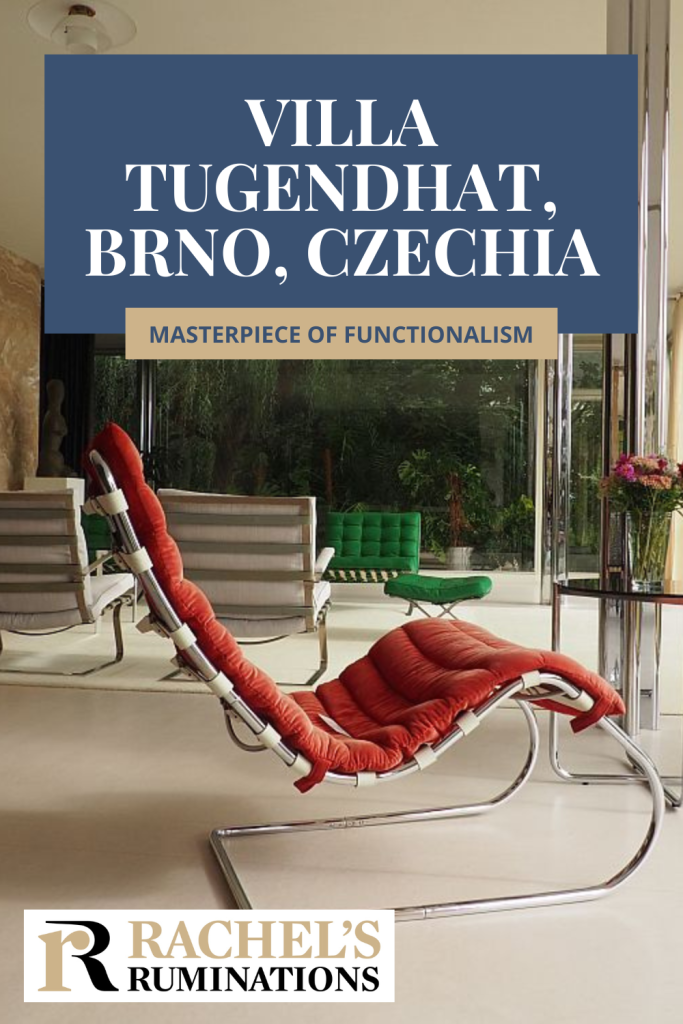

The signature walls that I mentioned above are the real eyecatchers. A semi-circular wall of Makassar ebony surrounds the round dining table of black pear tree wood. The table is adjustable in size by removing concentric rings of the tabletop. Even more eye-catching is the thin wall of onyx, beautiful with natural veining, that backs the living room space, dividing it from the work space. If you visit on a sunny winter morning, apparently, the sunlight through the onyx shines orange.

Because the architecture itself was intended to be an artwork, the house had – and has – very few art pieces: originally it was just the single statue in the living room. The furniture, most of which Mies van der Rohe designed himself, along with his colleague Lilly Reich, is in a functionalist style, all steel and wood and leather.

Visiting Tugendhat Villa

After a brief introduction outside the front door, our guide led us into the house. The first order of business was to protect the villa’s floors. We used a machine that we stepped into one foot at a time and which molded plastic around our shoes.

Our guide explained the house rules: no touching anything, sitting on any of the furniture or leaning on the walls. No eating or drinking inside the house.

The 3rd floor

The 3rd floor – in other words, the street-level floor – holds the bedrooms and bathroom. They are small and rather plain, but with big windows out on the garden and some wonderful Mies van der Rohe furniture. The doors are unusual for the period because they reach floor to ceiling. Apparently Fritz Tugendhat wasn’t happy with this part of the design; he was afraid they would warp. Mies van der Rohe insisted that it had to be the whole design or he wouldn’t do it at all. Tugendhat gave in. The quality of the hardwood used for the doors means they have not warped despite their size and age.

The 2nd floor

The really impressive sight is one floor down from street level on the 2nd floor, where the living room, library and dining room are. The space is huge. It’s a bit hard at first glance even to tell where the room stops and the outdoors begins. There are no doorways between the spaces, though they could be divided using long drapes.

The guide went through her explanation, but then allowed us to walk around the space freely. It’s a beautiful place. It certainly seems livable, in a way that some “design” sometimes doesn’t – Piet Blom’s cube houses in Rotterdam come to mind. Though they appear quite cozy, there’s a lot of wasted and unusable space in them, making them very small.

On the contrary, Tugendhat Villa’s wide-open spaces and comfortable-looking furniture, some of it designed specifically for this house, create an inviting impression. Those few years that the Tugendhat family got to enjoy the house must have been very special.

Despite the emphasis of the architect on simplicity and clean lines, there are still many details to discover. The onyx wall, for example, has natural veining that is quite eye-catching. The library – really just a large built-in bookshelf – hides a small hidden room that once held both a safe and a wet bar. Another wall, where a small table and two chairs would have been a logical place to eat breakfast, has a built-in lighted panel . It’s the kind of spot you’d expect to be highlighting a piece of art, but in this case it’s just light for the sake of light. The view out of the floor-to-ceiling windows, too, is worth a long look. Besides the garden, there’s a view to the city of Brno.

Other spaces

You’ll also see the working rooms: kitchen, storage and other spaces. Like the rest of the house, these spaces are airy and light and clean and designed by Mies van der Rohe.

The machinery – including the mechanism for the windows – was downstairs in the 1st-floor basement. It’s still there, but now most of the basement is an exhibition hall with additional information about the house and its architect.

A few tips for visiting Tugendhat Villa

Reserve your tickets far ahead. They’re released two-three months ahead, and sell out two months ahead. Check often for the tickets you want, then book them as soon as they’re available. Tours run every day except Monday. Since they limit the size of the tours, fewer than 150 people can see the house per day.

The villa does not appear to be wheelchair accessible. You might be able to access the 3rd floor, where the bedrooms are, but not the rest.

Stiletto heels and large luggage are not allowed.

Book your accommodations in Brno here.

It seems to me that the best time to visit the house would be on a fall or winter morning when the sun is low. If you’re lucky and it’s sunny, you might get to see how the light shines through the onyx wall.

The villa offers a number of different tours ranging from a 40-minute outdoor tour to a 90-minute indoor tour that includes the technical floor. Reserve your tour through their website.

Architecture in Brno

If modern architecture interests you, BAM (Brno Architecture Manual) provides free self-guided tours of various neighborhoods in the city. On each tour, assuming you have internet, you can follow the “trail” and click to read about each building. Check their website here. There are plenty of other functionalist structures to see.