Things to do in Baden-Baden, Germany

You may never have heard of the German thermal towns I’ve written about so far – Bad Ems and Wiesbaden – but you’ve probably heard of Baden-Baden. What struck us most, particularly in Bad Ems and Baden-Baden, was how they manage to retain the elegant, rarified atmosphere of the old-style thermal spa towns.

[Last updated October 12, 2025]

There are lots of things to do in Baden-Baden, a town that is particularly impressive in terms of culture. Its population is small – only about 56,000 residents – yet it boasts five museums, including an excellent modern art museum; a grand theater; two thermal spas; and even its own philharmonic orchestra. In other words, the old thermal spa town tradition of the 19th century that catered to nobles and royalty and just plain wealthy visitors continues to this day.

Disclosure: Our visit to Baden-Baden was organized by Baden-Baden Tourism Board, which also provided us with a guided tour, arranged for the museums, spa, and casino to offer us free or discounted admission, and treated us to dinner at the Kurhaus. Heliopark Bad Hotel zum Hirsch sponsored our stay. They have no influence over what I write about my visit.

Another disclosure: This article contains affiliate links. If you click on one and make a purchase, I will receive a small commission. This will not affect your price.

Why is it called Baden-Baden?

The word baden is, apparently, an old plural form of the word bad, which means “bath.” However, there were other baden in the area. Since this town was within the territory of the Margraviate of Baden, it became known as Baden-Baden simply as a way to distinguish it from other ones like Baden-Durlach and Baden-Württemberg.

So what is there to do in Baden-Baden? You can tour the Roman baths, soak in a spa, pretend it’s the 19th century (stroll the Trinkhalle, eat and gamble in the Kurhaus, see and be seen along Lichtentaler Allee and the Kurpark), visit museums, stay in a spa hotel, take the waters, explore Hohenbaden Castle, and ride up a mountain to see the view. Read on for more info!

Tour the Roman baths

It’s not just about the 19th-century period of “taking the waters,” though. All of the spa towns we visited referenced their Roman history, but Baden-Baden has the most visible (and visit-able) remains of a Roman bath. This area was where the Roman Empire at its peak edged an area ruled by Germanic tribes.

The 19th-century Friedrichsbad was built, unfortunately, literally right on top of the original Roman bath. On the other hand, some of the ruin has been preserved as a museum.

To me, the ruins of the Roman bath didn’t look like much at first, but with the help of an audio guide and effective signage, it became clearer what I was seeing. The descriptions helped me visualize what the ruins once looked like, though what I could see was often the parts that the Roman bathers probably never saw: things like the small columns of bricks that held up the floor. The hot steam flowed through this space under the floor to heat the room above.

It is unusual in Roman bath ruins like the ones I saw in Ankara or Trier, for example, to see intact hollow bricks. This ruin in Baden-Baden has quite a few, making it much clearer how the rooms could stay so warm, even in cold weather.

Roman bath ruins: Enter from the pedestrian tunnel under Friedrichsbad. Open mid-March to mid-November daily 11:00-12:00 and 15:00-16:00; closed mid-November to mid-March. Admission (including audio guide): Adults €5, children 7-14 €2. Website.

Soak in a spa

Friedrichsbad

There are two spas in Baden-Baden. The Friedrichsbad is the one that is most evocative of the town’s 19th-century heyday as a thermal spa destination.

When gambling became illegal starting in 1867, spa towns like Baden-Baden had to find other ways to keep luring their lucrative guests to visit. Gambling was a big part of what drew people to the spa towns – that, along with the opportunity to see and be seen among Europe’s upper classes. “Taking the waters,” whether by drinking the mineral-rich water or bathing in it, was generally secondary to networking. Anyway, building Friedrichsbad was Baden-Baden’s way to keep them coming. Completed in 1877, its neo-Renaissance design undoubtedly appealed to the town’s wealthy visitors.

I did not get to see the inside of the Friedrichsbad because it was closed due to the pandemic. Judging from the pictures, its interior design is very Roman-bath-inspired, with marble columns and statuary galore.

Friedrichsbad’s unique selling point is that it combines Roman-style bathing with Irish hot-air baths. Visitors (naked or in swimsuits, depending on the day) pass through a circuit with 17 different stations at different temperatures and styles, taking about three hours.

Friedrichsbad: Römerplatz 1 in Baden-Baden. Open daily 9:00-22:00. Naked bathing on Monday, Tuesday, Thursday, Friday and Sunday. Bathing in swimsuits on Wednesday and Saturday. Admission €38, plus €19 if you want the soap brush massage. No children under 14. Website.

Caracalla Spa

We did get to enjoy the Caracalla Spa, a modern bath run by the same company as the Friedrichsbad and situated right next door. Here visitors wear their swimsuits except in the separate section with the saunas. It has large indoor and outdoor pools, with a wide variety of temperatures, fountains, bubbles and so on.

The name Caracalla, by the way, comes from the name of the Roman emperor in AD 210-ish, about the time when the Romans built the baths here.

Caracalla Spa: Römerplatz 1 in Baden-Baden. Open daily 8:00-22:00. Admission for bathing area only: €20 for 2 hours, €24 for 3 hours or €34 for all day. Admission for bathing and sauna area: €25 for 2 hours, €29 for 3 hours, and €39 for all day. Children under 7 are not allowed and children 8-13 must be accompanied by an adult. Website.

Pretend it’s the 19th-century

Baden-Baden drew all of the most important people of Europe in its day. Queen Victoria vacationed here, for example, as did Kaiser Wilhelm I. Any number of Russian royals came here, as well as noble families from all over Europe. Wealthy industrialists came too, probably hoping to forge connections through business or marriage to the nobility.

The elite who came to Baden-Baden were entertained by top musicians like Franz Liszt, Johannes Brahms, Hector Berlioz and Jenny Lind.

Stroll in the Trinkhalle

The 1842 Trinkhalle, which translates as “drink hall” is an elegant building with a long roofed colonnade supported by pillars. This was where the promenading took place when the weather was bad. Visitors met to gossip, make business deals, arrange marriages, flirt, and so on.

It’s called the Trinkhalle because in Baden-Baden, unlike some of the other spa towns, the emphasis was on drinking the water rather than bathing in it. Visitors could fetch their glasses of water inside the hall and promenade either outside in the colonnade or inside the hall.

Trinkhalle: Kaiserallee 3. Open daily 10:00-18:00. Admission: free.

Eat and gamble in the Kurhaus

The neo-classical Kurhaus next to the Trinkhalle dates to the 1820s and was originally called the “conversation house,” appropriately. It was built to house the casino as well as a restaurant, a theater and other event spaces and was gradually extended over the course of the next century as tourism numbers increased.

The casino today – Germany’s oldest – occupies an extension added in the 1850s. It has an extremely ornate belle-epoque interior that is quite splendid, with carved statues, huge chandeliers and so on. Unfortunately, they don’t allow any photos, but I got this one from the Baden-Baden Tourism Board:

While you’re at the Kurhaus, stop for a meal at the Kurhaus Restaurant, which serves remarkably elegant food. The two long, low buildings in the space between the Kurhaus and the Theater are home to some very high-end little boutiques. Called the Kurhaus colonnades, they date to 1867. On a warm day, the tree-shaded space between them is a pleasant place to enjoy a cool drink or ice cream. Kurhaus website.

Casino Baden Baden: Open daily, but hours vary for different games. Must be 21 or over and there is also a dress code. See their website.

See and be seen along Lichtentaler Allee and the Kurpark

Like any self-respecting thermal town in the 19th century, Baden-Baden offered formal green parkland with tidy paths for strolling when the weather was good. The Kurpark is where you’ll find the Trinkhalle as well as the Kurhaus, where the casino is.

Lichtentaler Allee is the best place to get a feel for what it might have been like in the thermal town era. It’s a long strip of parkland that used to be the path to an abbey outside of town. To this day it’s still a great place to take a stroll. Passing the extravagant theater (from 1861), strolling past the colorful flowerbeds and stately trees, you pass museums on one side and elegant hotels on the other side of a small stream.

Visit the museums

Several of Baden-Baden’s museums are along Lichtentaler Allee. Starting at the Theater, you’ll pass four:

Kulturhaus LA8

This design museum focuses on the 19th century, complementing the city’s history as a 19th-century spa destination. It explores the 19th-century technological development of things like photography, transportation, industry, archeology and much more.

Kulturhaus LA8: Lichtentaler Allee 8. Open Tuesday-Sunday 11:00-18:00. Admission: Adults €9, children 13-18 €3, 12 or under free. Website (in German).

Staatliche Kunsthalle

The neoclassical Staatliche Kunsthalle (State Art Gallery) has no collection of its own, instead hosting visiting contemporary art exhibitions.

Staatliche Kunsthalle: Lichtentaler Allee 8a. Open Tuesday-Sunday 10:00-18:00. Admission: Adults €7, children €3. Combined ticket with the Museum Frieder-Burda: €18. Website.

Museum Frieder-Burda

This museum stands out the most in terms of architecture: a modern white and glass structure of simple geometric forms. Its collection is mostly works of modernism, including some late Picassos.

Museum Frieder-Burda: Lichtentaler Allee 8B. Open Tuesday-Sunday 10:00-18:00. Admission: Adults €16, children under 12 free, children 13 and up €6. Combined ticket with the Staatliche Kunsthalle: €18. Website.

City Museum Baden-Baden

This history museum is further down the Lichtentaler Allee from the art museums. Housed in what was originally a villa, it looks at local history from the Roman period until World War II.

Stadtmuseum Baden-Baden: Lichtentaler Allee 10. Open Tuesday-Sunday 11:00-18:00. Admission: Adult €5, children 7 and up €2. Website.

There are a few other small private museums elsewhere in the city. The most interesting of these, in my view, is the Fabergé Museum. It holds a collection of 700+ Carl Peter Fabergé works, including three of the famous Easter eggs.

Faberge Museum: Sophienstraße 30. Open daily 11:00-18:00. Admission: For the gold exhibit €8, for the Faberge exhibit €21; for both €27. Children 13-18 €9. Children under 13 free. Website.

Stay in a spa hotel

We stayed in the Heliopark Bad Hotel Zum Hirsch, right in the center of the town. It’s the oldest hotel in Baden-Baden, and even before it became a hotel in 1689 it was a bathhouse, with an outdoor pool and bath tubs going back to the 14th century. Today it is a four-star hotel with art-nouveau décor. We had quite a grand room – complete with chandeliers – overlooking a quiet street.

What’s really special, though, about the Heliopark Bad Hotel, is that the spa water is available in some of the rooms: those advertised as having a “thermal water connection.” These rooms have a bathtub that has two sets of taps: one dispensing standard city water, while the other has thermal water from the local spring. Guests can “take the waters” in the privacy of their hotel rooms!

If you’re looking for some pampering, there are several other spa hotels in Baden-Baden, though I’m not sure if any of the others have the in-room thermal spring water. And of course there are plenty of other hotels. Use the map below:

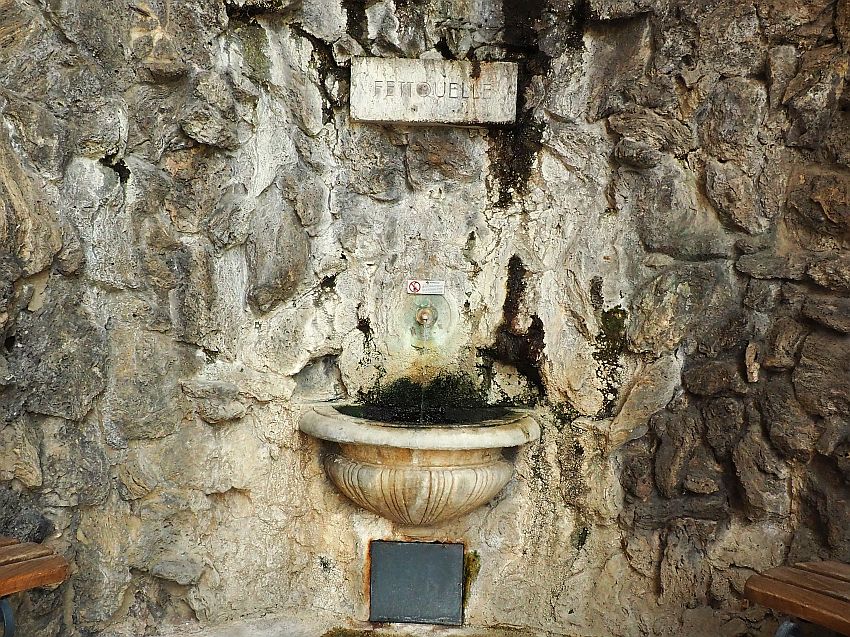

A note about the water

Interestingly, if you come upon one of the old fountains, you’ll notice a sign that warns not to drink the thermal water. You may also see that people are, nevertheless, drinking it. According to our tour guide, people have drunk this water for centuries. Nowadays, though, with more knowledge of the minerals involved in this “healthy” water, the authorities decided that it was unsafe to drink. This had to do with the fact that arsenic is one of those minerals, as are other not-generally-considered-safe elements such as strontium, but all in very small quantities.

As a compromise of sorts, the town, protesting the closure of all of its fountains, negotiated a deal: they’d be allowed to keep a few of the fountains open, but they would post a sign at each instructing people not to drink it. If you stay at the Heliopark and have one of the rooms with thermal water taps, you’ll notice a similar sign warning you against drinking the water. You can see it in the bathtub photo above.

And yes, I did taste it. Like all mineral water, it tasted like rocks to me: hot salty rocks. A sip was more than enough. If it’s something you want to try, go ahead. The amount of dangerous minerals including arsenic is so small that I seriously doubt it would do you any harm, and it tastes terrible anyway.

You might also want to read these other articles from the region:

Things to do just outside of town

Visit Hohenbaden Castle

High on a hill overlooking Baden-Baden is a huge castle ruin called Hohenbaden Castle, dating to the 12th century. It housed and protected the Margraves of Baden until the 15th century, when they moved to a palace below in the valley.

It was clearly a very large castle once: you can spot the fireplaces on multiple floors of the remaining walls. Visitors can climb to the top of the castle tower and walk on some of the walls too. The views from up there of Baden-Baden and the surrounding Black Forest are magnificent if you visit on a clear day.

Hohenbaden Old Castle: Alter Schlossweg 10, Baden-Baden, north of the city in the direction of Ebersteinburg. Drive there, or walk for about an hour, or rent a bike or scooter to get there. Always open. Admission: free. Website.

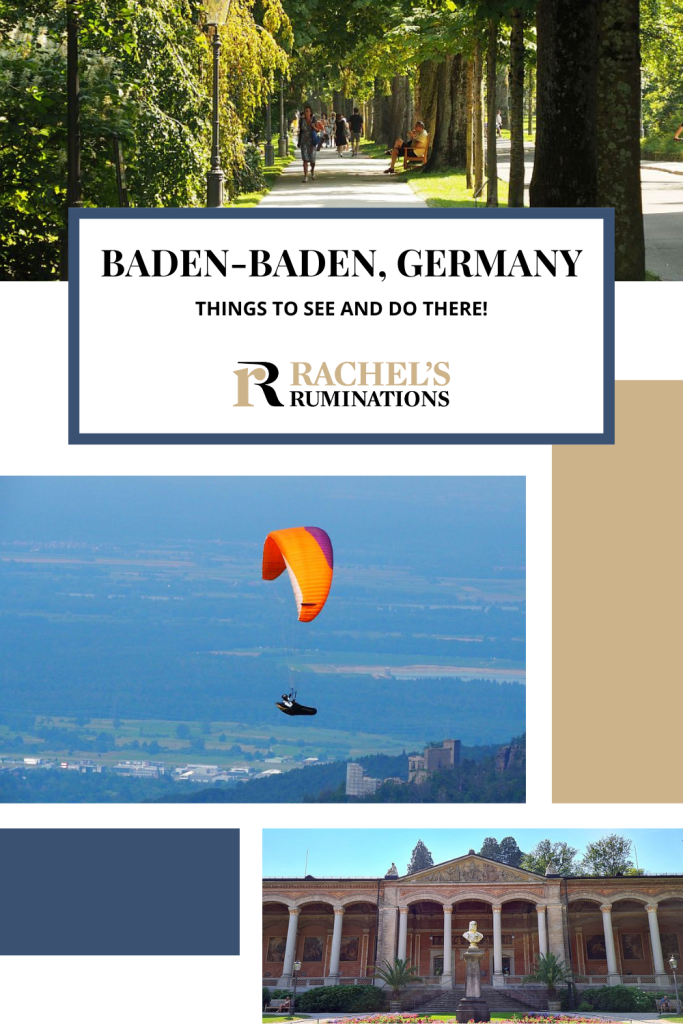

Ride the Merkurbergbahn to see the view

Another fun thing to do in Baden-Baden is the Merkurbergbahn. The longest funicular railway in Germany, it takes visitors to the top of Merkur Mountain, where there’s plenty of walking to do and views to see. The mountain is 668 meters high (2,191 feet), and you can add another 23 meters by taking the elevator up the Merkur Tower at the top.

We ended up stopping at the little café at the upper funicular station and watching a procession of paragliders taking off from the steep field next to the café.

Merkurbergbahn: Merkuriusberg 2, Baden-Baden. Take the 204 or 205 bus and buy a combination ticket from the driver. Open daily 10:00-22:00. Admission: Round-trip adult €8.50, children 6-15 €4.50; one-way adult: €6, children €3.50. Website.

Historic Thermal Towns and UNESCO

Because so much of this famous thermal town is intact, Baden-Baden, like Bad Ems, is part of the European Historic Thermal Towns Association (EHHTA) and is one of the 11 spa towns included in the UNESCO designation called The Great Spa Towns of Europe.

I think it’s probably clear from my description that visiting Baden-Baden allows an immersion into thermal spa history, art and architecture that is well worth a visit, preferably a few days, to truly relax and enjoy the waters and stroll the town.

Have you visited Baden-Baden? Do you have any additional recommendations?

My travel recommendations

Planning travel

- Skyscanner is where I always start my flight searches.

- Booking.com is the company I use most for finding accommodations. If you prefer, Expedia offers more or less the same.

- Discover Cars offers an easy way to compare prices from all of the major car-rental companies in one place.

- Use Viator or GetYourGuide to find walking tours, day tours, airport pickups, city cards, tickets and whatever else you need at your destination.

- Bookmundi is great when you’re looking for a longer tour of a few days to a few weeks, private or with a group, pretty much anywhere in the world. Lots of different tour companies list their tours here, so you can comparison shop.

- GetTransfer is the place to book your airport-to-hotel transfers (and vice-versa). It’s so reassuring to have this all set up and paid for ahead of time, rather than having to make decisions after a long, tiring flight!

- Buy a GoCity Pass when you’re planning to do a lot of sightseeing on a city trip. It can save you a lot on admissions to museums and other attractions in big cities like New York and Amsterdam.

- Ferryhopper is a convenient way to book ferries ahead of time. They cover ferry bookings in 33 different countries at last count.

Other travel-related items

- It’s really awkward to have to rely on WIFI when you travel overseas. I’ve tried several e-sim cards, and GigSky’s e-sim was the one that was easiest to activate and use. You buy it through their app and activate it when you need it. Use the code RACHEL10 to get a 10% discount!

- Another option I just recently tried for the first time is a portable wifi modem by WifiCandy. It supports up to 8 devices and you just carry it along in your pocket or bag! If you’re traveling with a family or group, it might end up cheaper to use than an e-sim. Use the code RACHELSRUMINATIONS for a 10% discount.

- I’m a fan of SCOTTeVEST’s jackets and vests because when I wear one, I don’t have to carry a handbag. I feel like all my stuff is safer when I travel because it’s in inside pockets close to my body.

- I use ExpressVPN on my phone and laptop when I travel. It keeps me safe from hackers when I use public or hotel wifi.