Falun Copper Mine UNESCO site in Sweden

“It’s a big hole in the ground.”

I think “underwhelmed” is a good word for my first impression of the Falun Copper Mine in eastern Sweden.

We were on our way south on a road trip from the northernmost part of Norway back home to the Netherlands after our Hurtigruten cruise up the Norwegian coast. As usual, I looked up any UNESCO sites we happened to be passing, and this was one of them.

It wasn’t until we took a closer look – and read the UNESCO site’s description – that we understood the place’s significance. In any case our visit was educational and interesting.

Disclosure: This article contains affiliate links. If you click on one and make a purchase, I will receive a small commission. This will not affect your price.

Falun Copper Mine and the UNESCO designation

It’s easy to forget that UNESCO sites are about humanity’s cultural and natural heritage. It’s not necessary for the place to be really old or particularly beautiful. It has to have “outstanding universal value” from whatever point of view: art, history, science, aesthetics, architecture, conservation, habitat, natural beauty, to name just some of the categories. The sites also have to be actively protected by the country or locality.

In this case, the mines were important in the Swedish economy over centuries, and they’re in good condition, providing “a vivid picture of what was for centuries one of the world’s most important mining areas.” (from the UNESCO site).

Called “Mining Area of the Great Copper Mountain in Falun” on the UNESCO site, the UNESCO designation isn’t just for the “Great Pit.” It includes the planned town of Falun that dates to the 17th century, as well as remains of the copper industry across much of the region.

History of the Falun mine

Copper mining in Falun probably started over a thousand years ago. It produced copper and other metals, and the industry in turn contributed enormously to Sweden’s development to a modern state, especially in the 17th century.

At its height, the mine produced more than two-thirds of all European copper and more than a thousand people worked there. This includes children who worked picking ore from gravel.

Technology improved, bringing tools like dynamite and drills that were powered by steam and later electricity. Electric lighting replaced oil lamps. It wasn’t until the 20th century that mine workers gained some protections in terms of things like helmets and an eight-hour work day.

The mine didn’t close until the late 20th century, and the remains of the machinery, the mine shafts, as well as the town are still in excellent condition. They illustrate the mining industry as it was conducted both in the pre-industrial period and later, as the technology improved.

Underground at the Falun copper mine

Getting back to my first impression, we saw a very large, very deep pit. What helped us understand it more was to go down a mining shaft. Not surprisingly, this is only possible as part of a guided tour.

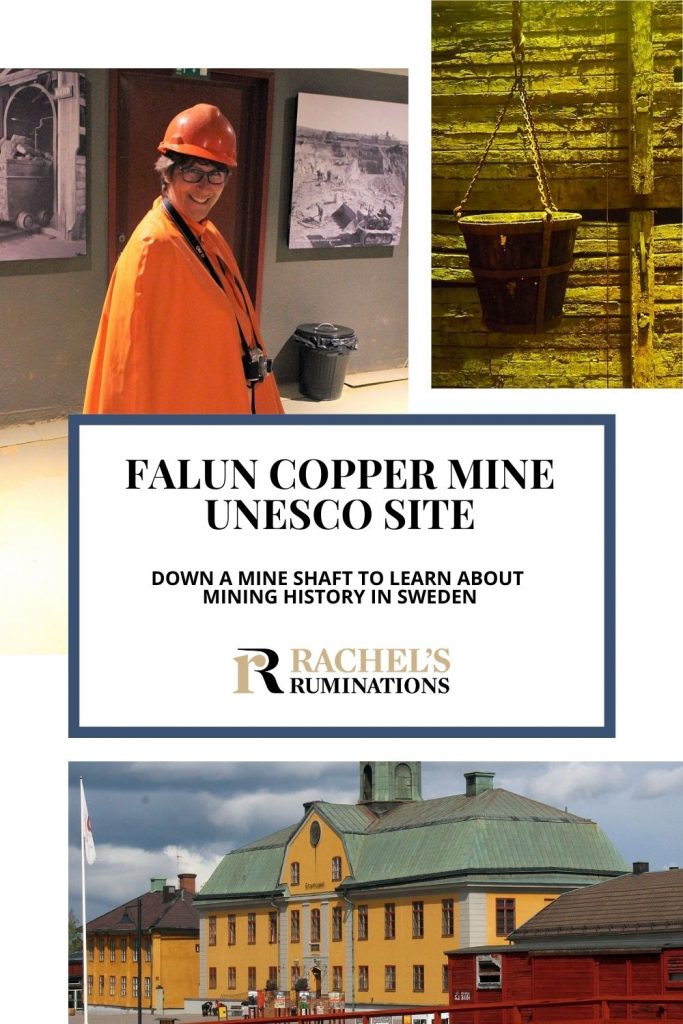

The tour takes about an hour and goes to a depth of about 67 meters out of the mine’s 610 meters total depth. Before descending, we put on bright orange rain ponchos and hardhats. It’s wet down in the mine, and presumably not 100% safe, or we wouldn’t need hardhats.

The tour involved first going down a lot of steps, then walking some damp gravel-floored tunnels, some with wooden boards to walk on. They were dark, despite the electric lights shining at intervals. We stopped at various points to hear stories from the mine’s history, along with descriptions of how the workers extracted the copper.

It wasn’t pretty. We could see for ourselves how in some places the reddish walls were supported by massive wooden beams holding back rubble, and could easily imagine how common wall or ceiling collapses must have been. In some places we saw the remains of rickety-looking ladders or stairs made of wood. We saw side tunnels filled with rubble. Was someone there when the rubble came down?

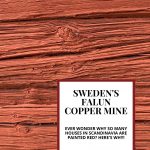

We looked up a shaft, light filtering down dimly through the dust, with a large pail hanging on the end of a chain. While the pail was mostly used for carrying ore, sometimes it carried the workers themselves. They would be lowered into the mine with that pail, several at a time with one leg in the pail, one leg out, hanging on to the chain with their hands as they descended.

While the route we took had been widened and smoothed for visitors like us, I could imagine how miserable the job must have been for those miners. Breathing in dust all day as they worked at the rock, always wary of collapses, backs bent. The whole thing made me nervous, and I was happy to arrive back above ground after our one-hour tour.

Above-ground at the Falun mine

Above the ground there is more to see. A path two kilometers long runs along the edge of the Great Pit, and signposts explain the items along the way. Mostly the landscape is dotted with slag heaps or “tips,” i.e. huge piles of rock tailings. This rock was pulled up out of the mine shafts and dumped here after the ore was removed. Little grows on them; they’re just piles of rocks.

The Great Pit was not always so big, of course. In the 17th century it was actually two large pits. In 1687 a huge landslide collapsed the wall between the pits and caused landslides underground inside the tunnels. No one was hurt, fortunately, because it was Midsummer and the whole staff had a free day.

Several buildings edge the pit, and each served a function. Some of them are called a “lave” and sit on top of shafts from various periods. A wheelhouse holds a huge water wheel used for power to haul the ore and rock out of the mine.

The Mine Museum

We took a little time as well to visit the Mine Museum in the old mine office next to the pit, and the quality of the exhibits surprised us. It’s very interactive, and the number of children focused on the various activities testifies to its success at making the science surrounding mining interesting.

Another museum of a sort is Eriksson’s cottage, where employees in period costume show what life was like for the miners’ families in 1897.

Falun Red paint

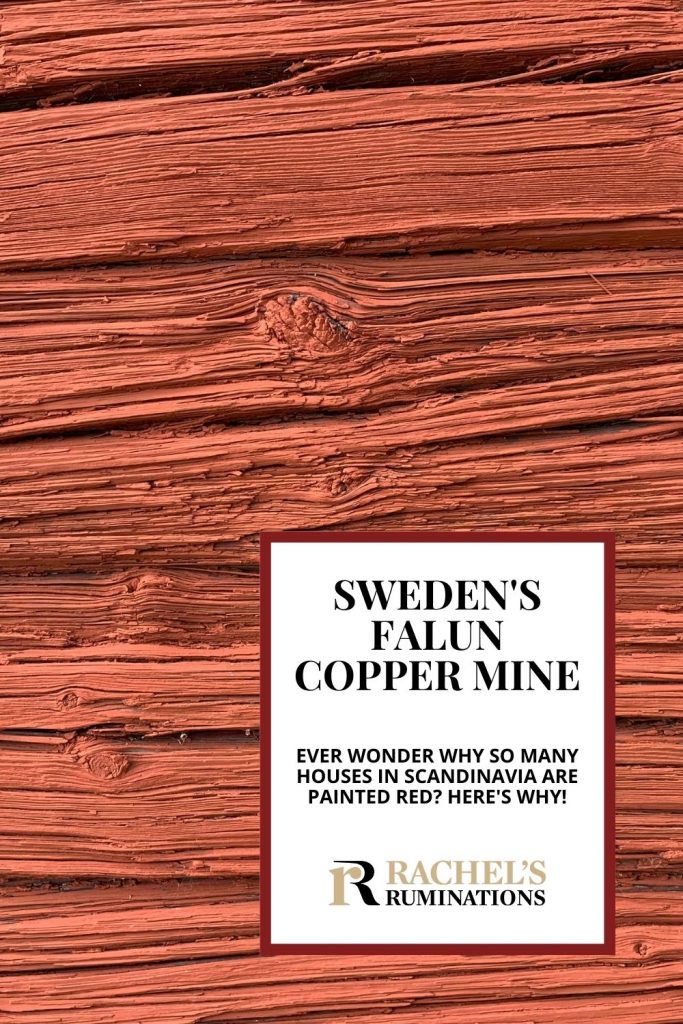

It wasn’t just copper that came out of the mine, by the way. Zinc, lead, gold and silver also came from Falun mine. But the most famous product, besides copper, is Falun Red paint, also called Falu Red. This is the dominant color you’ll see on houses all over Sweden and the rest of Scandinavia. The traditional big red barn in the US may derive from this too.

Falun Red paint is a byproduct of heating copper ore. The color varies depending on how much it gets heated. Mixed with oil and starch and other trace ingredients, it becomes an excellent protective paint. Over time it fades, rather than flaking, so it’s easier than other paints to repaint it without having to sand.

At the Falun Copper Mine, a small craft company still produces Falun Red pigment from the tailings found around the mine. You can visit their gift shop on the site.

Falun town

The extraction of copper from the pit evolved over the centuries, as did the town serving the mine. That town, also called Falun, was planned and built in the 17th century and is today a charming collection of wooden houses, painted red, of course. Make sure to leave time for a stroll around the town.

Other UNESCO sites nearby

If industrial history is a particular interest of yours, don’t miss Engelsberg Ironworks, south of Falun Copper Mine. It’s UNESCO-listed because it’s a well-preserved ironworks that, like the Falun Mine, contributed to Sweden’s prosperity in the 17th to the 19th century. I didn’t get there, but it sounds from the UNESCO site like it includes a whole complex of original ironworks buildings as well as offices and residences.

Moving north of the Falun Copper Mine, you’ll head into the region of the Decorated Farmhouses of Hälsingland. You can read about them in my separate post here.

Way up at the top of the Gulf of Bothnia – the body of water between Sweden and Finland – you’ll find the city of Luleå and the absolutely charming UNESCO site called Gammelstad. My separate post about that is here.

If you visit Falun Copper Mine

If you go to Falun, here are some suggestions:

- Wear strong, closed shoes. You’ll walk a lot of steps and it may be wet.

- Wear several layers, even if it’s warm out. It’s cold in the mine.

- If you’re traveling with children, keep a good hold on their hands to keep them on the path and safe.

- The tunnel is not at all accessible if you can’t walk stairs. There is a video tour of the tunnel in the Mine Museum.

- If you’re claustrophobic, don’t do it. Watch the video in the museum instead.

- I think the path around the edge of the mine is wheelchair accessible, but some of the small buildings are not.

- We spent probably about 3-4 hours there, what with the tour, the path around the pit, and the Mine Museum. With kids it could easily take quite a bit longer in the museum.

Where to stay

If you need a place to stay, there’s a B&B on the mine site called Gruvortens in an 18th century building that once was the residence for the chief engineers of the mine.

There are plenty more places to stay in or near Falun. Use the map below to see the listings: