Elie Wiesel Memorial House: A museum with a message

I am ashamed to admit that when we passed through the small city of Sighetu Marmaţiei, in the north of Romania, it was just a place to stop for the night on our way home to the Netherlands. Our GPS was about half a block off in directing us to the hotel we’d booked randomly that afternoon. I got out of the car to search for it while my husband double-parked.

That’s when I passed an intriguing little museum: The Elie Wiesel Memorial House and Museum of Jewish Culture in Maramures. Elie Wiesel, the Holocaust survivor, author and activist, was born and raised here until he was forced into a ghetto and then deported, along with the entire local Jewish population, to Auschwitz. He survived; both of his parents and one of his three sisters did not.

In his Nobel Prize acceptance speech in 1986, he spoke about himself as that teenager, caught up in the deportation:

I remember: it happened yesterday, or eternities ago. A young Jewish boy discovered the Kingdom of Night. I remember his bewilderment, I remember his anguish. It all happened so fast. The ghetto. The deportation. The sealed cattle car. The fiery altar upon which the history of our people and the future of mankind were meant to be sacrificed.

I remember he asked his father: “Can this be true? This is the twentieth century, not the Middle Ages. Who would allow such crimes to be committed? How could the world remain silent?”

This little museum does two things. First, it recounts and honors Elie Weisel’s life story in Sighet, as the town was then called, then in Auschwitz, and later, as an activist and author in the US. And it serves as a memorial to the region’s Jewish community, destroyed in the Holocaust.

An Ordinary Middle-Class Home

Yet what struck me most about the Elie Wiesel Memorial House was its ordinariness. It was a cozy, plain, middle-class home. A radio sits on a table in the living room, and you can imagine the family gathering around it after dinner. A tiled furnace, common in Eastern Europe, stands in the corner to heat the room. Candlesticks on the table are exactly the same ones my grandmother used to light on Friday evenings to mark the beginning of the Jewish Sabbath. An ordinary middle class home.

And now the boy is turning to me. “Tell me,” he asks, “what have you done with my future, what have you done with your life?” And I tell him that I have tried. That I have tried to keep memory alive, that I have tried to fight those who would forget. Because if we forget, we are guilty, we are accomplices.

Leaving the living room, visitors enter a section of the museum with displays about Wiesel’s life after the war – his writings about his experiences at Auschwitz and his efforts to make sure that the world remembers the Holocaust. He was outspoken in drawing parallels between the persecution and genocide of the Jews and other examples around the world of similar oppression, racism and “ethnic cleansing.”

And then I explain to him how naïve we were, that the world did know and remained silent. And that is why I swore never to be silent whenever wherever human beings endured suffering and humiliation. We must take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented. Sometimes we must interfere. When human lives are endangered, when human dignity is in jeopardy, national borders and sensitivities become irrelevant. Wherever men and women are persecuted because of their race, religion, or political views, that place must – at that moment – become the center of the universe.

The memorial part of Elie Wiesel Memorial House is basic and low key. A neat chart on the wall tallies up all of the surrounding cities and towns, horrifying and cold in its factual approach: next to each town is the Jewish population as of four different dates. On the list, Sighet is the biggest town: in 1910 the Jewish population was 7981. In 1930 it was 10,154. In 1948, 1515 survived. By 1992, only 33 remained. Many of the smaller towns had no survivors at all.

Also read my posts on the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe in Berlin, the Jewish Museum, also in Berlin, and Auschwitz in Poland.

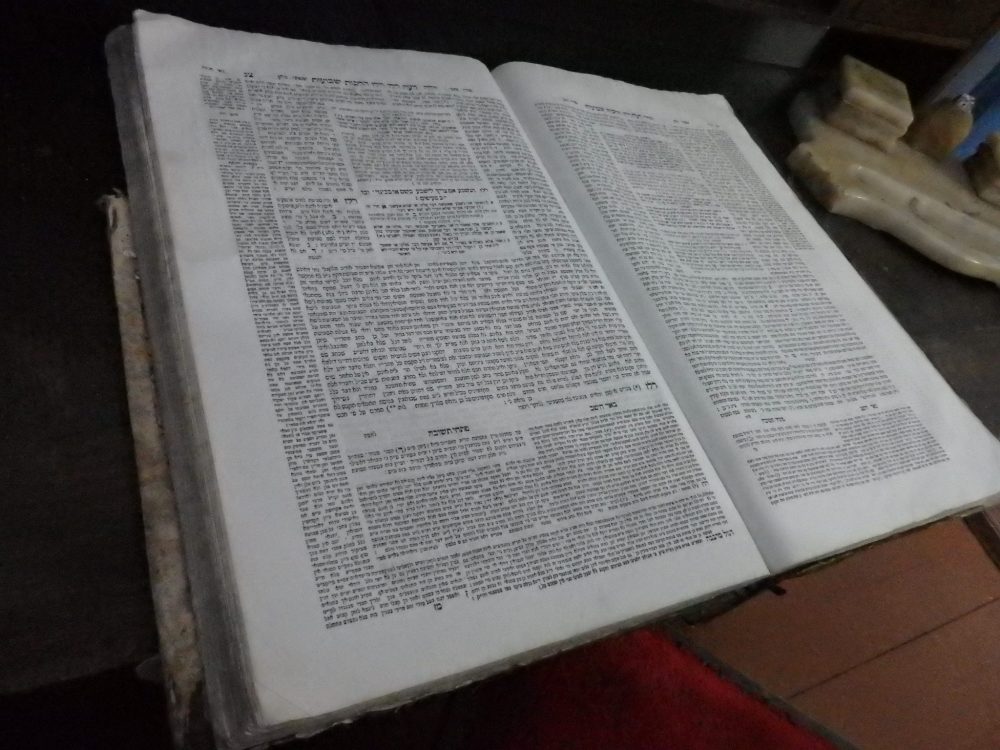

A few family photos and Jewish artifacts offer a portrait of the Jewish community before the war. Other simple displays in text, charts, photos, and maps recount the whole series of events leading up to and including the deportation of the Jewish community: their forced toil in labor battalions and other restrictions placed on them, and their confinement in small ghettos.

In the small backyard, a carved stone declares that this is a memorial to the Jewish victims from Northern Transylvania-Maramures. The rest of the space holds a plain concrete Star of David set into gravel. A few park benches around its perimeter are presumably meant for quiet contemplation.

There is so much to be done, there is so much that can be done. One person – a Raoul Wallenberg, an Albert Schweitzer, Martin Luther King, Jr. – one person of integrity can make a difference, a difference of life and death. As long as one dissident is in prison, our freedom will not be true. As long as one child is hungry, our life will be filled with anguish and shame. What all these victims need above all is to know that they are not alone; that we are not forgetting them, that when their voices are stifled we shall lend them ours, that while their freedom depends on ours, the quality of our freedom depends on theirs.

While the Elie Wiesel Memorial House is respectful, and Wiesel’s message seems loud and clear, I fear it’s not reaching the people outside its walls who need to hear it. Romania, after all, is remarkably unfriendly to the refugees reaching its borders in the current refugee crisis. Discrimination against the Romani people too is practically normal in Romania. And I could name many other nations that are guilty of such victimization.

As Elie Wiesel said, “There is so much to be done,” here and all over the world.

Details: The museum is on the corner of Strada Dragoş Vodă and Strada Tudor Vladimirescu in Sighetu Marmaţiei. Open Tuesday-Sunday 10-18:00 in the summer and Tuesday-Sunday 8-16:00 in the winter. Admission: 10 lei (about US$2).

I didn’t realize Wiesel was from Romania. This sounds like a lovely little museum and memorial – it’s too bad the words of Wiesel seem to be getting so lost everywhere.

This sounds like an important little museum to have stumbled across. The contrast between the ordinariness of the house and the horrors experienced would be particularly poignant. There is indeed still much to be done.

Yes, the same with, for example, the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam. She had pictures of movie stars cut from magazines on her wall when she was in hiding. So ordinary.

I also didn’t realize that Wiesel was Romanian. As today’s news swirls around me, I feel myself asking the same thing he did sometimes, “How can this be happening?” Only now, it’s the 21st century and he asked this question in the 20th century. Sigh.

It’s scary, isn’t it. Sometimes it seems like things could turn really bad, really quickly. Probably just what the Germans thought.

Rachel, Thank you for sharing this. I did not know about this museum, and it sounds like a very special place. When in the Netherlands, we visited some of the lesser known places that helped the Jews during the holocaust. I am glad that you included some of Weisel’s words.My husband, continually asks, ‘why is it that you need to bring up horrific past history?’ And as you point out, Weisel says it well, – ” Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented. Sometimes we must interfere. When human lives are endangered, when human dignity is in jeopardy […]’ It is so important to speak out and not stay silent. Unfortunately too many people think they should be silent so they can stay untouched by the horrors.

Yes, but it’s not really surprising, is it. I mean, people prefer to think happy thoughts, and these sorts of topics bring us down. And yet, if you point it out, most would understand and agree, at least in the abstract, that it’s important to remember. They just don’t think they’re the ones who need to remember.

What a special little museum the Elie Wiesel Memorial House is to happen upon. So much to see, so little time.

I know!

Such a moving and timely post Rachel and sadly, Mr. Wiesel’s two questions, “Who could allow such crimes to be committed?” and “How could the world remain silent?” are still unanswered today. What luck to find the Elie Wiesel museum and thank you for such a heartfelt tribute to a man whose words remain as relevant today as when they were written decades ago. Anita

Thanks for the supportive words, Anita!

hey! it should be noted that this post contains misinformation; his two older sisters also survived. they were later reunited in a French orphanage.

I apologize. I knew his younger sister had been killed, but didn’t know he had two older sisters who survived. Their names were Beatrice and Hilda. I’ll change it in the article.