Citizen of a Parallel World

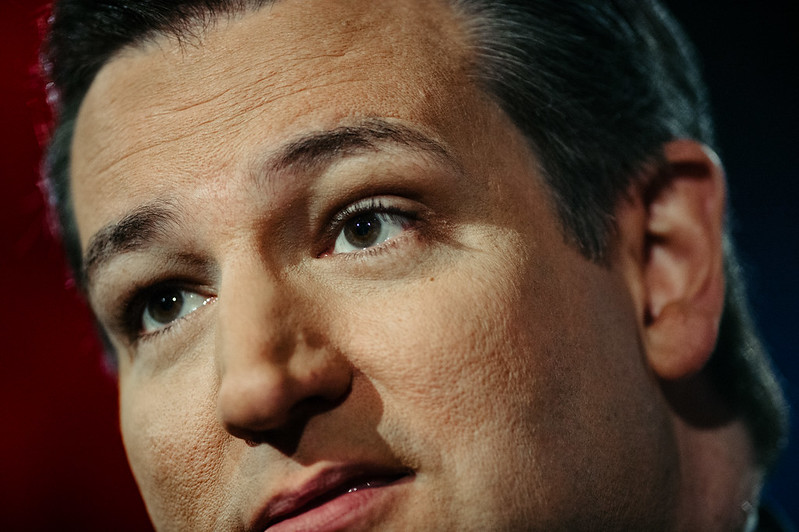

This week the Board of Elections of Illinois decided that Ted Cruz is indeed a natural-born citizen as required by the US Constitution to be eligible to be President.

Ted Cruz was already identified as a US citizen because his mother was a US citizen. His birthplace, however, is in Canada, hence the question of whether he is “natural born.”

A Parallel World

Just for the fun of it, I’d like to take you through a thought experiment around Ted Cruz, and what it means to be a citizen.

In a parallel world that looks very much like our world, the only thing that is different is that every country defines citizenship as the US does:

- You’re automatically a citizen if you were born in the US, even if you left when you were a newborn and never went back.

- You’re automatically a citizen if either of your parents is a citizen, even if you have never set foot inside the US.

- Taxation, in this parallel world, is citizenship-based, rather than residence-based. That means that you are taxed where you live, but must also pay taxes to any other country where you have citizenship.

- Anyone living outside their citizenship country is required to send their financial information (assets as well as income) to that country. The banks in all countries are also required to send your financial information, so that your country (or countries) of citizenship can check that you are reporting everything accurately.

- In order to lose citizenship, you have to actively renounce, for which you have to pay a fee of $2350.

- In order to enter or leave the country of which you are a citizen, you must have a passport from that country, even if you have a valid passport from another country.

- If you owe back taxes and/or fines above $50,000, your passport can be taken away from you.

A Citizen of Canada

Let’s say that Ted Cruz has won the election and is now President of the United States. Because there was so much discussion of his citizenship during the campaign, the Canadian government has been alerted to the fact that Cruz was born in Canada.

![flag map of Canada by DrRandomFactor (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://rachelsruminations.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/2048px-Flag_map_of_Greater_Canada-e1454694540310.png)

The Canadian Revenue Agency (CRA) sends him a registered letter informing him of his obligation to bring his tax status up to date. An amnesty will allow him to file only the last five years of tax forms, but he will have to pay taxes to Canada on any income above about $100,000. As a resident of the US, he already pays income taxes at home.

In addition, he has to inform the Canadian government of his assets in the US, so they can check that he’s not hiding money “overseas” in the US. He will have to report the totals on any accounts he has signing authority on, which include his offices in the White House, his Presidential campaign accounts, possibly some of the Treasury Department accounts, and all of his private accounts anywhere in the world besides Canada.

Cruz, surprised and horrified that he is expected to file and pay taxes in a country where he has never considered himself to be a citizen, and especially upset that he has to report his personal accounts, as you can imagine, considers just refusing to pay. After all, how is it Canada’s business how much money he has in his accounts?

However, the banks that hold these accounts inform him that they will be sending his bank account information, including all balances, to the Canadian government, complying with a tax treaty signed between the two countries. So he hires an accountant to fill in the CRA forms for him. He applies to renounce his Canadian citizenship, but it is all very time-consuming and expensive.

In his role as President, Cruz starts the long process toward renegotiating the treaty with Canada. Canada’s argument, though, is that the laws are in place to catch tax cheats who try to move money out of Canada. If this is inconvenient to other, law-abiding, Canadian citizens, they’re very sorry, but it’s necessary.

A Citizen of Cuba

Cruz’s life gets even more complicated when we look at Cuba. Cruz is strongly critical of Barack Obama for lifting the embargo on Cuba and paving the way for improved relations, since Cruz’s father was imprisoned and tortured by Batista and fled to America. His aunt also fled to America after being tortured under Castro.

Cruz has made clear statements on how he thinks the US should deal with Cuba. As President, he has pursued those plans, and Cuba has made significant concessions to his demands. It’s time for a face-to-face meeting with Raul Castro.

In our parallel world, though, Cruz is a Cuban citizen. His father thinks he gave up Cuban citizenship more than 40 years ago, when he took on Canadian citizenship (later renounced). However, the Cuban government does not accept renunciation that has not been carried out according to their rules, which include a renunciation fee and filing of back years of tax returns. So, in their view, Ted Cruz’s father is still a Cuban citizen, and that makes Ted Cruz a citizen as well.

If he didn’t have diplomatic immunity as President, Cruz would not be able to go to Cuba for this meeting; he might get arrested for tax evasion. He has no Cuban passport, so he’d be breaking the law anyway by entering on a US passport. Even if he had one, it could very well be taken away from him, stranding him in Cuba, because he’s undoubtedly accumulated lots of debt in taxes and fines.

The situation would not help his campaign for re-election, so he suggests they meet somewhere in the European Union instead.

It turns out they can’t meet there either. Castro, according to Spanish law, is a Spanish citizen because his father was born in Spain. Castro, like Cruz, has not filed his back tax forms or renounced. If he goes there, he might be arrested for tax evasion. And he doesn’t have a Spanish passport either…

The Real World

Well, you get the idea. In the real world, only the US and Eritrea do this kind of reaching out into other countries to identify people as their citizens in order to tax them. (Eritrea does not allow renunciation and imposes a 2% income tax on all expatriate Eritreans.)

Which brings up the question of how we define “citizen.” Each country defines it in its own way, usually involving some combination of where you were born, who your parents are, and where you live. I wrote last week about the US definitions, and how the result of US legislation is that US citizenship consists of different classes.

Most countries, though, leave you alone if you live in a different country. You only pay taxes where you live: residence-based taxation.

It seems obvious to me that the US’s citizenship policies are wrong and extend its powers far beyond its borders. Citizenship goes without saying if you are born in a particular country and continue to live there. But for people outside that category—people born outside the US, or people who were born there but didn’t stay—it should be a choice we each make, and which we can apply for. The country would then decide if we qualify.

Renunciation should also be a choice, and it should be attainable without exorbitant fees. Citizens of most countries have these rights. Why don’t Americans?

Additional note, added on February 6, 2016: Apparently I wasn’t as original with this post as I thought I was. This article by Don Whiteley from last September imagines what would happen if Kenya followed the same laws as the US regarding citizenship and taxation!

Feel free to comment below, but please keep it civil!

My whole US citizenship series:

- Part 1: Giving up US citizenship?

- Part 2: Republicans, expatriates, and FATCA

- Part 3: How my citizenship hit me in the gut

- Part 4: My renunciation day

- Part 5: Thanksgiving reconsidered

- Part 6: FATCA, the Tea Party, and me

- Part 7: Individual freedom, self-reliance and renunciation

- Part 8: Equality? Competition? Not overseas!

- Part 9: The American Dream

- Part 10: The irony of renouncing under duress

- Part 11: Open letter to President Obama in response to the State of the Union Address

- Part 12: 7 Reasons NOT to renounce

- Part 13: Citizenship matters

- Part 14: Citizen of a parallel world

- Part 15: Renunciations in the news

- Part 16: Vote … as a non-citizen? Really?

- Part 17: The ridiculous story of a pilot and his taxes

- Part 18: On receiving my Certificate of Loss of Nationality

- Part 19: So you think you want to emigrate…

- Part 20: Indignation Fatigue and FATCA

- Part 21: The US election, as seen by Americans overseas

- Part 22: On receiving my California voter ballot

- Part 23: Watching America fall apart on my renunciation anniversary

Having a U.S. citizen parent does not automatically make one a U.S. citizen – there is a certain amount of time the parent had to have lived in the U.S. before the child’s birth to pass citizenship down. Even then, precedent appears to hold that such a child is not actually recognized as a U.S. citizen until if and when the parent (or the child if 18+) registers the birth and obtains a CRBA (the document issued to such children born abroad). If your parents never registered you to the U.S. authorities (and you don’t have a U.S. birthplace) then you could probably just stay low and not acknowledge your potential U.S. citizenship. It’s the other way around (parents with no ties to the U.S. except they were in the country temporarily when you were born) that leaves you stuck with registered U.S. citizenship and a U.S. birthplace – and part of that residency requirement that I said above (unless BOTH parents are U.S. citizens) requires that a certain amount of that residency be after the parent turned 14, so any “accidental Americans” who left the country before then and never lived there again since can’t pass the citizenship down.

Yes, that’s all true. I didn’t want to get into the details too much. I would add, though, that although a child born abroad who hasn’t been registered could certainly lie low, like you said, legally the US would still consider them a citizen, if they ever became aware of them.

I just wanted to make sure you didn’t have the impression that citizenship could be passed down indefinitely through the generations (especially since you brought up the point that Ted Cruz could be a citizen of Spain).

No, in this hypothetical situation, Castro, not Cruz, could be a citizen of Spain, since his father was born in Spain. I realize that in most countries citizenship doesn’t go further back than one’s parents — though in some places it can.

Sorry I overlooked that it was Castro and not Cruz – my fault.

Not True

My two daughters cannot become US citizens because they were born in France, their mother is French and I have not lived 2 years after the age of 14 in the US. So even if they wanted to become US citizens they can’t.

True. Citizenship doesn’t keep getting passed down according to US law: some residency is required after the first generation. I was referencing all those first generation accidental Americans out there right now, who do have citizenship, particularly ones like my son who are the kids of people who moved abroad for love or work. I didn’t want to confuse the story with too many details. I don’t know how long Castro’s father lived in Spain, but I think he moved as an adult.

Here’s a link that explains it all and will help everyone (I looked it up a year ago to see if my 2 daughters would be impacted by FATCA, thankfully not because even if they wanted to, thay can’t becom US citizens) :

https://travel.state.gov/content/travel/en/legal-considerations/us-citizenship-laws-policies/citizenship-child-born-abroad.html

Thank you for the link!

alstublieft (you’re welcome for those who don’t speak dutch 🙂

It’s all very technical and I’m glad it doesn’t have an impact on my life! Or does it.