Taking the waters at European hot springs

If you’ve watched the series “Bridgerton” or seen a filmed Jane Austen novel (or read one), you’ll have a picture in your mind of high society in Britain in the early to mid-1800s. Picture the scenes that take place in Bath, with women in long dresses carrying parasols and men in jackets and top hats, promenading. They went there, ostensibly, to “take the waters,” but the real business was social.

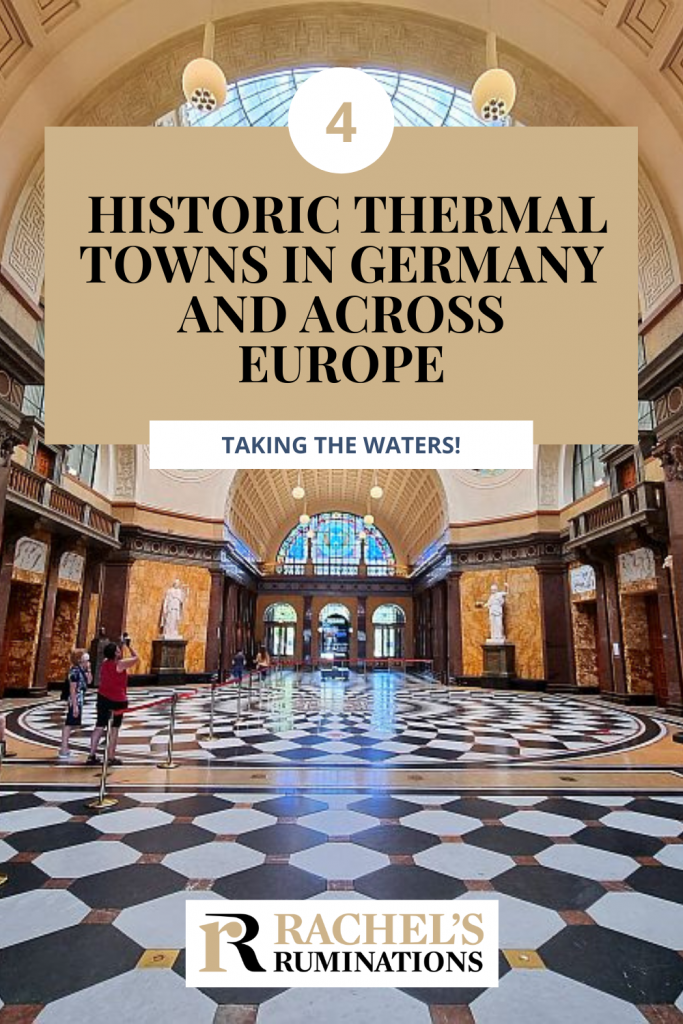

The European Route of Historic Thermal Towns

This society really existed, and not just in Bath. All over Europe in the 19th century, nobles and royals traveled to European hot springs to “take the waters.” Many of these thermal towns are still spa towns today, and they’ve united as part of the European Historic Thermal Towns Association, (EHTTA) one of the Council of Europe’s Cultural Routes.

Disclosure: Parts of this trip were sponsored by the tourism boards of the four towns in Germany I describe below. This article is an introduction: I will write separately about each of the four German thermal towns in future articles. All opinions are my own. I’m very grateful to the staff of the European Historic Thermal Towns Association for their help in organizing the sponsorships and giving me lots of great advice in planning it.

And another disclosure: This article contains affiliate links. If you click on one and make a booking, I will receive a small commission. This will not affect your price.

Each of these towns has grown around a natural spring or several springs, the water coming from deep underground. On its way to the surface, it picks up all sorts of minerals from the rocks it passes through. That affects its flavor as well as its purported impact on health.

In some cases people started visiting these springs many centuries ago in Roman times – some still have Roman ruins associated with them. Over time, a unique kind of town grew around many of them, each offering things like accommodations and entertainment for the people coming to the springs to take the waters: a kind of proto-tourism. The towns still offer these things today, and the European Historic Thermal Towns Association was created to promote modern-day tourism.

There are more than 40 towns in the group at the moment, and more joining all the time. They’re all over Europe and east to Turkey.

You might also enjoy these articles about destinations in Germany:

Taking the waters

“Taking the waters,” in the heyday of these spas, could mean people drinking spring water for their health or bathing in that same spring water, either hot or cold. Especially in the 19th century, the visitors – some were nobility or royalty, but many were just plain wealthy – stayed in opulent hotels, some of which had thermal baths within their premises. The royal classes might rent out an entire hotel and its staff to house themselves and their courtiers. Others built or bought their own stately villas.

These visitors would stroll outside in manicured parks or inside in ornate halls built for this purpose. While they strolled, they gossiped and flirted – carefully, one mustn’t be considered flirtatious! – and marriages were arranged, everyone aiming to move up the social ladder. Families with titles were greatly in demand for marriages, and royalty even more so. The men also tried to make connections to improve their business position: royals could favor their business ventures and the wealthy could become investors.

In other words, while these places were – and still are – billed as “thermal towns,” in fact the warm spring water wasn’t really the point in some of them. It was the excuse to make those social and business connections. I suppose it would sound a lot better to say “I’m going to spend a few weeks in Bad Ems to take the waters for my gout” than to say “I’m going to Bad Ems because I want to meet the Kaiser so that he can help me make a business deal.”

These thermal towns had casinos as well, but again, it was better to say that you were there to take the waters than to gamble away your fortune!

Four thermal spa towns in Germany

My husband and I recently visited four of these thermal towns in Germany, all very different, but all conjuring the image in my mind of those wealthy classes parading along the promenade.

Bad Ems

Bad Ems was the first we visited, and the town still looks much as it did in the 19th century. The premiere hotel, then as now, is today called Häcker’s Grand Hotel, and it certainly is grand. The spa inside the hotel is remarkable in its opulence, all marble and shine. Apparently both a Russian Czar and Kaiser Wilhelm I have stayed here.

The promenade – yes, it’s still there – is along the Lahn River, and fountains offer warm spring water here and there along the promenade.

The Kursaal (“cure room,” translated literally), not far from Häcker’s, is an elegant building that was once the place where the upper classes mingled, listened to musicians and gambled in an ornately-decorated hall. Today it still fulfils the same functions.

If you don’t stay at Häcker’s, fear not. A new thermal bath house called Emser Therme is not far down the river. It offers pools, whirlpools, saunas and steam rooms of various types and temperatures.

Since Bad Ems is today a center for what is now called rehabilitation rather than cures, people still come for treatments of various kinds. Many of the beautiful 19th-century buildings offer housing for rehabilitation centers or serve as clinics.

If you’re planning a trip to Bad Ems, use this link to book accommodations.

Read more about Bad Ems in my separate article.

Bad Homburg vor der Höhe

Bad Homburg has a similar history and boasts of the same historical upper-class visitors as Bad Ems. In particular, we heard Kaiser Wilhelm I and II mentioned, the Romanovs of Russia, as well as Dostoyevsky, who was apparently a compulsive gambler and had a tendency to gamble away the money meant to pay for his hotel.

Nevertheless, Bad Homburg has a different look. For one thing, it’s a bigger city; the thermal town part is a bit separated from a much older historical city center, where you’ll find half-timbered houses and a castle. Its thermal town attractions dot a large park and include the original spa, called Kaiser-Friedrich Therme. It’s a stately domed building, still used for thermal baths and a variety of spa treatments. There’s also, of course, a Kurhaus for strolling and socializing. There is still a casino.

Bad Homburg’s outdoor promenade is a path through the very pretty 44-hectare (109 acres) Kurpark. These parks are common to many of these thermal towns: they were carefully designed to match a 19th-century, idealized and romanticized view of “nature” in the landscaping. To these 19th-century visitors, staying healthy involved enjoying the beauty of nature on a regular basis.

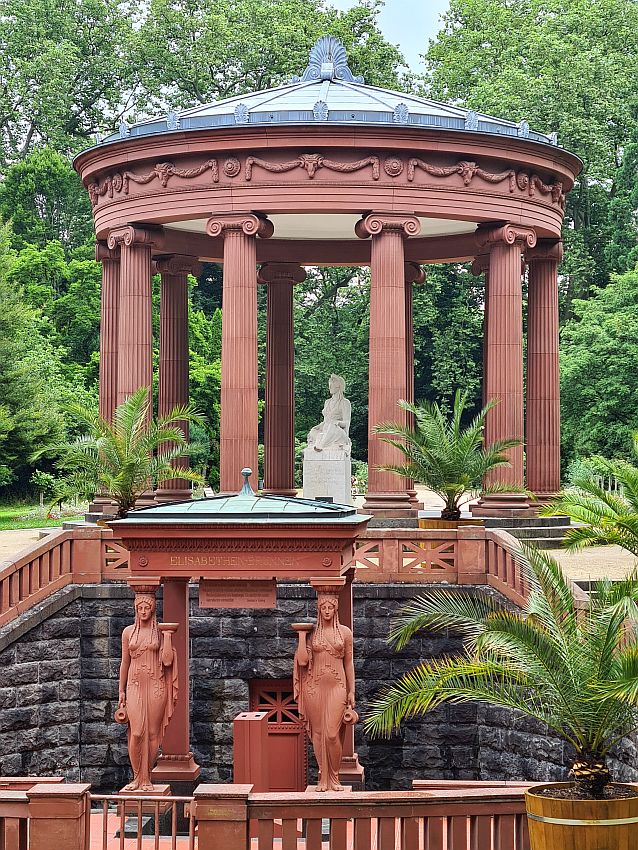

Bad Homburg’s park is dotted picturesquely with springs. Each spring is topped by a fountain, and each tastes slightly different from the others. Some taste saltier, some sweeter (To be honest, they all taste like rocks to me.). Apparently, while they ultimately all come from the same source very deep down in the earth, the water passes through different layers and picks up different minerals at each location, affecting the flavor.

The park also has various structures – domes held up by columns usually – sheltering statues or springs. Kaiser Wilhelm designed some of them himself.

Bad Homburg isn’t particularly reliant on being a thermal town anymore, basing its economy on consultancies and insurance companies.

If you’re planning a trip to Bad Homburg, use this link to book accommodations!

Wiesbaden

Wiesbaden’s water is quite different from Bad Homburg’s or Bad Ems’s water. It’s got a lot of iron in it, and that means it stains things a reddish yellow. Apparently the ancient Romans used it as a hair dye here, near the limits of the Roman Empire.

Wiesbaden claims to have 26 springs. One fountain bubbles in a central square, caked with yellowish build-up, which has to be chipped off from time to time to avoid destroying the fountain. Other fountains dot the spa district, and the water certainly tastes metallic. Wiesbaden still has a spa industry, with a couple of general thermal baths as well as various specialty clinics.

Wiesbaden’s historic Kurhaus is massive and ornate, all neoclassical marble and pillars and chandeliers. It dates from early in the 20th century and was commissioned by Kaiser Wilhelm II. It still holds a casino and, here too, Dostoyevky’s name comes up in connection with gambling.

Like the other thermal towns we visited, Wiesbaden has a green and manicured park for promenading in. The Hessian State Theater (1894) on its edge is a fitting Baroque Revival backdrop.

To book your accommodations in Wiesbaden, click here!

To read more about Wiesbaden, go to my separate article: 23 Fun Facts about Wiesbaden.

Baden-Baden

Certainly the most well-known of the German thermal towns, Baden-Baden, like Bad Ems, still has much of its 19th-century architecture, making it easy to picture the life of the elites of the time. The Trink Halle (Drink Hall) is where the promenading happened and where the elites drank the water, but that was just the excuse. If the weather was good, they strolled or rode their carriages in the Lichtentaler Allee, a long, manicured park.

Baden-Baden’s 19th-century architecture is particularly plentiful and grand, especially the Friedrichsbad bathhouse, the theater with its neo-classical facade, the Trink Halle and the Kurhaus, which now houses the casino.

Speaking of casinos, if you are ever in Baden-Baden, I’d certainly recommend a visit to the casino, inside the old Kurhaus. I have no pictures because photos are not allowed, but the décor inside is an extravagant period piece: massive chandeliers and pillars carved with classically-inspired figures.

For a small town, Baden-Baden has a lot to offer even today, continuing the 19th-century tradition of high culture. It has a philharmonic orchestra, for example, and several quality museums. And, of course, two thermal bathhouses:

- The Friedrichsbad is the historic one. It promotes bathing in “Roman-Irish” style, which means being naked and passing through a tour of 17 “stations,” each offering different temperatures of air and/or water, steam baths and brush massage.

- The Caracalla Spa is a more typical modern-style spa. It offers an assortment of pools and fountains and whirlpools (clothed), as well as a sauna area (naked).

By the way, the Friedrichsbad stands literally on top of the ruins of a Roman-era thermal bath. The bath is viewable inside an underground museum. It has elements that are surprisingly well-preserved and well-displayed.

You can book your Baden-Baden accommodations through this link!

Read more about Baden-Baden, including why it has that odd name, in my separate article.

Other thermal towns in the EHTTA

The European thermal spa towns that are part of EHTTA are:

- Austria: Baden bei Wien

- Azerbaijan: Galaalti

- Belgium: Spa

- Croatia: Daruvar Spa

- Czechia: Karlovy Vary

- Estonia: Parnu

- France: Bagnoles de l’Orne, Châtel-Guyon, Enghien-Les-Bains, La Bourboule, Le Mont Dore, Louchon, Royat-Chamalières, and Vichy

- Germany: Bad Ems, Bad Homburg, Wiesbaden, Baden-Baden and Bad Kissingen

- Greece: Istiea Aedipsos, Krinides-Kavala, Loutra Pozar, and Loutraki

- Hungary: Budapest Spas

- Italy: Acqui Terme, Montecatini Terme, Montegrotto Terme, and Salsomaggiore Terme

- Luxembourg: Mondorf-les-Bains

- Poland: Lądek-Zdrój

- Portugal: Caldas da Rainha and São Pedro do Sul

- Portugal and Spain (cross-border): Chaves-Verin

- Spain: Caldes de Montbui, Mondariz-Balneario, and Ourense

- Turkey: Afyonkarahisar and Bursa

- UK: Bath

This isn’t a complete list of historic thermal towns, because some members of the EHTTA are regions rather than specific towns. For example, the Galicia Region of Spain is a member, and claims 300+ mineral springs and 21 thermal spas spread across the region.

The Great Spas of Europe transnational UNESCO World Heritage site(s)

While the EHTTA includes more than 40 spa towns in Europe and will certainly grow, a more elite group of thermal towns has formed. As the “Great Spas of Europe,” they applied for and recently received a UNESCO designation as a World Heritage Site.

This group of spas towns across Europe is smaller: just 11 towns. What unites them is that they have all preserved the atmosphere and structures from their 18th, 19th and early 20th century period of popularity as thermal towns. This includes the unique assemblage of architecture created to cater to spa visitors – spas, hotels, galleries, hospitals, theaters, concert halls, etc. – and the idealized “natural” park lands and promenades that also supported this leisure activity.

As you probably guessed if you read about the German spa towns above, Bad Ems and Baden-Baden are members of this elite club. Here’s the full list:

- Austria: Baden bei Wien

- Belgium: Spa

- Czechia: Karvoly Vary, Františkovy Lázně and Mariánské Lázně

- France: Vichy

- Germany: Bad Ems, Baden-Baden and Bad Kissingen

- Italy: Montecatini Terme

- UK: City of Bath

The birth of modern-day tourism in Europe

These historic spa towns represent an industry that has become one of the biggest on the planet today: tourism. There was tourism before these thermal towns developed, of course, but for the most part only the wealthiest classes could afford it. Little infrastructure was developed to accommodate them. The wealthy in England might take, for example, the “Grand Tour,” a long, months-long tour around the great cities of Europe. There were hotels or inns along the way, of course, but not entire towns devoted to these travelers and organized around them.

These towns that grew around hot springs in Europe were to some degree planned urban areas. They were intended to appeal to these tourists looking for both treatments and social contact. Each town built whatever was necessary to keep the visitors entertained and housed. Being purpose-built destinations is what makes the historic thermal towns unique. You could say they represent the birth of modern tourism.

Have you been to any of these historic thermal towns? What did you think? Add a comment below! And please share this post on social media!

I have been to Baden Baden, and I would love to visit the other spa towns in Germany. Bad Ems looks so pretty!

Julia x

https://www.thevelvetrunway.com/

Bad Ems is really pretty, and smaller than Baden-Baden. I liked them both!