What to see in Brno: 3 macabre sights

What to see in Brno? An ossuary, a crypt full of mummies, and a nuclear bomb shelter. Somehow the one day I spent sightseeing with my husband in Brno, Czechia, turned out distinctly macabre.

Disclosure: This article contains affiliate links. If you make a purchase through one of these links, I will receive a small percentage. It will not affect your price.

And a warning: This article has some rather gruesome pictures of the dead. Not suitable for all audiences.

Site #1: The Ossuary underneath the Church of St. James

The Church of St. James (Kostel sv. Jakuba) is a typical late Gothic church built in the 13th-16th century. St. James Square next door was the church’s graveyard for hundreds of years: from the 13th to the 18th century. As the city grew, and the size of the graveyard stayed the same, the community had a problem. Their burial place didn’t have enough space, especially given episodes like the plague and other epidemics.

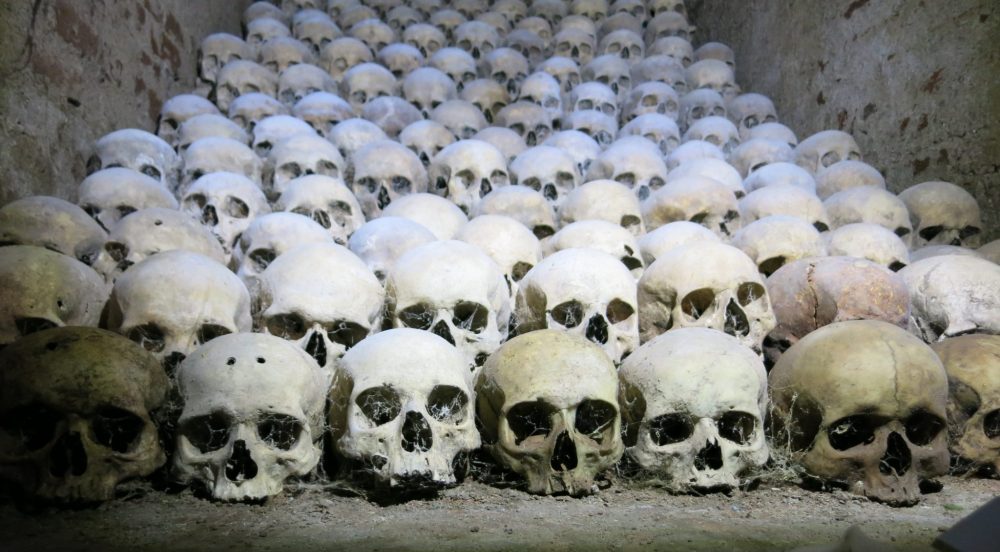

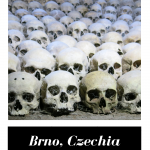

So what to do? The church leaders started reusing the graves. About 10-12 years after a burial, they would dig up the remains, now reduced to bones, and deposit them in an underground ossuary nearby. This filled up quickly as well and was expanded several times. When I say “full,” I mean piled to the ceiling with bones.

In the 18th century, the graveyard was closed and paved over to become St. James Square. The ossuary faded into history, largely forgotten.

Eventually, in 2001, archeologists rediscovered the ossuary during a routine pre-construction archeological dig.

Since then, studies of the bones and the ossuary chambers have led to an estimate that the collection consists of more than 50,000 skeletons. Originally neatly piled, they were all jumbled up by the time they were found, presumably by water that leaked into the chambers.

You might want to stay in Brno for a night or two. Use the map below to find and compare accommodations:

Visiting the ossuary

The entrance to the ossuary is next to St. James Church. A stairway leads down from the sidewalk into a series of arched spaces. Atmospheric lighting and background music add to the reverent, somewhat spooky feeling entering the ossuary. Brick-built hallways lined with old tombstones lead between the rooms, which have been tidied and emptied to accommodate visitors.

What happened to the bones when the spaces were cleared? Most were piled up in a neat and extremely compact way: creating walls and columns of bones, punctuated by skulls. Despite the fact that the bones take distinctly less space than they once did, somehow this serves to emphasize the sheer number of bones.

In one section, the bones lie in a heap, almost to the ceiling, held back by a plate of Plexiglass. Apparently this is how the excavators found the ossuary: a jumble of thousands of bones, so, with the placement of the glass, visitors can see how the ossuary originally appeared.

Adding to the feeling of reverence that the arrangement encourages, modern sculptures dot the rooms, again artfully lighted. Despite the contrast between the recent artworks and the ancient walls and bones, it works. It makes it a place of respect and prayer, rather than a morbid tourist attraction.

The Ossuary under the Church of St. James: St. James Square (Jakubske namesti), Brno. Look for the stairway down near the entrance to the church. Open Tues.-Sun. 9:30-18:00. Admission: Adult CZK160 (€6.50/$6.60), children 6-15, students and seniors CZK80 (€3.25/$3.30). Website.

Site #2: The Capuchin Crypt

Looking at the Capuchin Church of the Finding of the Holy Cross, you’d never guess what’s inside. Painted a pale pink, this pretty early baroque church is fronted by a row of baroque statues added about a century later, depicting various saints.

From 1656 until 1784, monks in the Capuchin monastery next door left deceased monks and important benefactors of their community in the crypt below their church.

When I say “left,” that’s exactly what I mean. Eschewing luxury, even in death, these men, who had dedicated their lives to the church, were denied even a coffin. Or, rather, they shared one coffin. During the funeral, the deceased lay in a coffin. Afterwards, the monks removed the body and placed it on the floor of the crypt in simple monk’s robes, arms crossed, sometimes clutching a cross or rosary.

A strange thing happened, though. The bodies didn’t decompose. They dried and shriveled, but that was all. They were naturally mummified. Of the 205 people laid to rest in the crypt, 41 remain, 24 of whom were Capuchin monks.

In 1925, the church leaders made a decision. In their view, these mummified remains had a purpose: memento mori. That means “remember you must die.” In other words, the bodies had not decomposed in order to remind living people of death, and of the fact that it comes for everyone.

Visiting the crypt

Entering the crypt, after being warned that this is a place of reverence and reflection, we first came upon a glass-topped coffin. The mummy displayed here is Franz Baron van Trenck, an 18th century mercenary who fought for Russian Empress Anna Ivanovna and then later for Habsburg Empress Maria Theresa. Accused of causing an Austrian defeat, he was court-martialed and sentenced to death in 1746. One of the Brno Capuchin monks was his confessor in prison, and Trenck repented his sinful life. He requested and received burial in the Capuchin crypt.

An exhibit about the frescoes in the Loretto Crypt in Prague fills the next room. Then we entered the tomb itself, where the first three chambers hold the glass-topped coffins of prominent members of the church community.

Further in, we looked through bars into a room lined with bodies: the Capuchin friars. They lie on the dirt floor in a square, with their heads to the wall and their feet toward the center. Shriveled, dressed in simple cassocks, they are an eerie sight. Memento mori, indeed. I couldn’t believe I was looking at a roomful of dead bodies.

To quote the website of the Capuchin Church: “We wish that the uniqueness of this place excelled – a place that confronts us so directly with the finiteness of our earthly existence and with questions over its true sense.”

The Capuchin Crypt: Capuchin monastery on Capuchin Square 5 (Kapucínské náměstí), Brno. Open Apr.-Oct. Mon.-Sat. 9:00-12:00 and 13:00-18:00 and Sun. 11:00-17:00. Open Nov.-Mar. Mon.-Sat. 10:00-16:00 and Sun. 11:00-16:30. Closed in the days around Easter and Christmas. Admission: Adult CZK120 (€5/$5), children, students and seniors CZK70 (€3/$3). Photo permit CZK30. Website.

You might also be interested in the following articles about sights in Czechia:

- UNESCO sites in the Czech Republic outside Prague (This includes another Brno site: the Tugendhat Villa.)

- Kutna Hora UNESCO site and a macabre church (more bones!)

- What to see in Trebic, Czech Republic

- A UNESCO site in Olomouc (and other things to see there)

- Five synagogues in Prague (and one cemetery)

Site #3: The 10-Z Bunker

Our third macabre sightseeing stop in Brno has more to do with avoiding death than dying. Yet the thought of any nuclear bomb shelter from the Cold War, at least in hindsight, is tinged with hopelessness and death, isn’t it? To the people who built them, though, they must have represented hope.

The Germans built the 10-Z Bunker during World War II, not as protection against nuclear bombs, just regular ones. After the war, it housed a winery, but when the Communists took over in 1948, they took over the shelter as well.

In the general tension of the Cold War, the Communist leadership re-purposed the bunker to serve as a nuclear bomb shelter for local government and military leaders, not to save the citizenry. Dug straight into a hill, it’s made up of a network of tunnels, all stocked and equipped to allow 500 people to survive a nuclear attack for about three days.

Today it’s a museum and illustrates the fear, resourcefulness and general craziness of life in the Cold War.

Visiting the 10-Z Bunker

Exploring the tunnels, we came upon a range of spaces dedicated to different tasks. One large room brimming with pipes and machinery was the air filtration center, apparently still in working order. It could pull air from the outside, filter it and distribute it throughout the shelter … at least until the fuel ran out to run the generator nearby.

An office room is littered with propaganda of various sorts, including a copy of The Communist Manifesto that reminded me of the dog-eared copy I still have that belonged to my mother (“Know thine enemy.”)

We saw an emergency telephone exchange that fills a room, and another room holding a period telephone switchboard. It’s not clear, though, who they’d be communicating with in a nuclear attack.

Here and there old-fashioned televisions broadcast 1950s television news and propaganda. While it’s all in Czech, it’s clear enough what the messages were. Often quite amusing now, in terms of production values and fashion, at the time it would have been all that was available to the common citizen.

If you’d like to learn more about Czechia in the Cold War era, read my article about Communist Prague.

Kofola

A kitchen (the “milk bar”) in the tunnels still operates, offering snacks, drinks and lunch. The tables stand along the sides of an entrance tunnel, and some of the tables are vintage radios.

When I tried to order a diet cola, the waiter told me they don’t carry Coke or Pepsi. Why not? “We only serve what was available in Czechoslovakia during the Cold War.” So instead I drank a local cola substitute, still popular today, called Kofola.

Kofola is nothing like cola, however. It was invented in 1959 in an effort to come up with something to do with the caffeine left over from coffee processing. It tastes rather earthy, with an unidentifiable mix of herbs.

You can explore 10-Z Bunker at your own pace, helped by a map you’ll receive at the entrance. You can also sign up for a one-hour tour that focuses specifically on the technical aspects of the facility.

10-Z Bunker: Husova Ulice, across from house number 12, Brno. Open Tues.-Sun. 11:30-18:15. Admission: Adult CZK150 (about €6/$6), child to 15 years CZK60 (€2.50/$2.50). Website.

Recommendations for what to see in Brno

While I admit to a rather morbid fascination with the ossuary and the Capuchin mummies, I would certainly recommend the nuclear bomb shelter over the other two sites. It allows an understanding of the reality of the nuclear threat during the Cold War, and the desperate hope to survive the nuclear war that to many seemed likely or even inevitable.

I grew up in Cold War America, where we learned a very “Us vs. Them” view of the world. It is interesting to me to see what the “Them” were going through at the time, and how they viewed us. They were just like us, in other words.

Getting there

Brno is a 2½-hour train ride from Prague. All of these sights are within a 15-minute walk of the train station. To see them all well, though, and especially if you are going to see the other main sight in Brno, the UNESCO-listed Tugendhat Villa, you should at least stay overnight, though two nights would work best. And if you want to see Tugendhat, you’ll need to reserve ahead of time. You can use this link to find accommodations.

If you enjoyed this article, please share it!

Updated July 2022.

This would be a perfect Halloween post – sorry. Fascinating post.

I admit I thought about waiting to post this closer to Halloween!

Who needs horror movies when you have places like these? I do not enjoy ossuaries or relicaries but have to say the most creepy part of your post were the mummies. That was a bit impressive. Hard t believe the practices people had in antiquity. I wonder if the odor of those bodies reaches the upper parts of the church. #TPThursday

I wondered that myself. They don’t smell now, but they must have smelled then! Of course, so did the recently deceased in most medieval churches. The ones who were buried under slabs on the floor inside the church (i.e. the wealthy) were never buried very deeply, hence the phrase “the stinking rich.”

Interesting for sure. I’ve seen skeletal bones in a church basement in Rome I believe many years ago but it was on a much smaller scale (nowhere near 50,000). An unusual sight-seeing day for sure.

Apparently this is the second biggest in the world, after Paris.

I have to admit that we have a certain fascination with all things slightly bizarre and I know we would have loved visiting Brno during our recent stay in the Czech Republic. The whole country has so many interesting things to see and do it begs for a repeat visit, doesn’t it? The Church of St. James ossuary has a similar background when compared to the Sedlec Ossuary in Kutná Hora where the graves were re-used and the bones stacked as space ran out. It seems rather strange though, that they never designated a 2nd location for burying the dead. Your photo of the Capuchin mummies all laid out in rows was great (in a rather chilling sort of way) and a tour of 10-Z bunker would really have been interesting. So glad you wrote this post about Brno Rachel, because it will be at the top of our list if we’re lucky enough to make a return visit to the Czech Republic. Anita

Yes, I hear you: a fascination for the bizarre. Which explains why we chose these three particular sights! I’d heard of the ossuary in Kutna Hora, but not this one, which is actually bigger. They did designate another location: when they closed the graveyard next to St. James Church, they moved to another graveyard outside the center of the city.

I’ve never heard of Brno before. Your images make the three sights you detail particularly vivid and interesting. I will opt to see them all when I’m in town.

There are plenty of other things to see. Somehow I just get drawn to the weird and quirky…

HI Rachel. I admit to finding this post disturbing. Perhaps I am too much of a Pollyanna. Interesting, though, to hear of Brno. I don’t think it will make it onto my must see list.

Don’t reject Brno because of this! These are the sights we chose to see. There are plenty of other sights in Brno!

Wow, nothing like stopping for a coffee in a nuclear bomb shelter! Probably a better idea than having an espresso in an ossuary, though! 🙂 Creepy post and I loved it.

Glad you liked it. It was actually a pleasant place to have lunch. It was quite hot inside and rather cool in the bunker!

What a fascinating collection of stops in Brno!. Like you, Rache, I grew up in the Cold War USA and I remember well the fear, the hope, the sometiems feeling of inevitability of a nuclear attack. That shelter would be an eerie reminder.