An outstanding art museum in the Hague: Mauritshuis

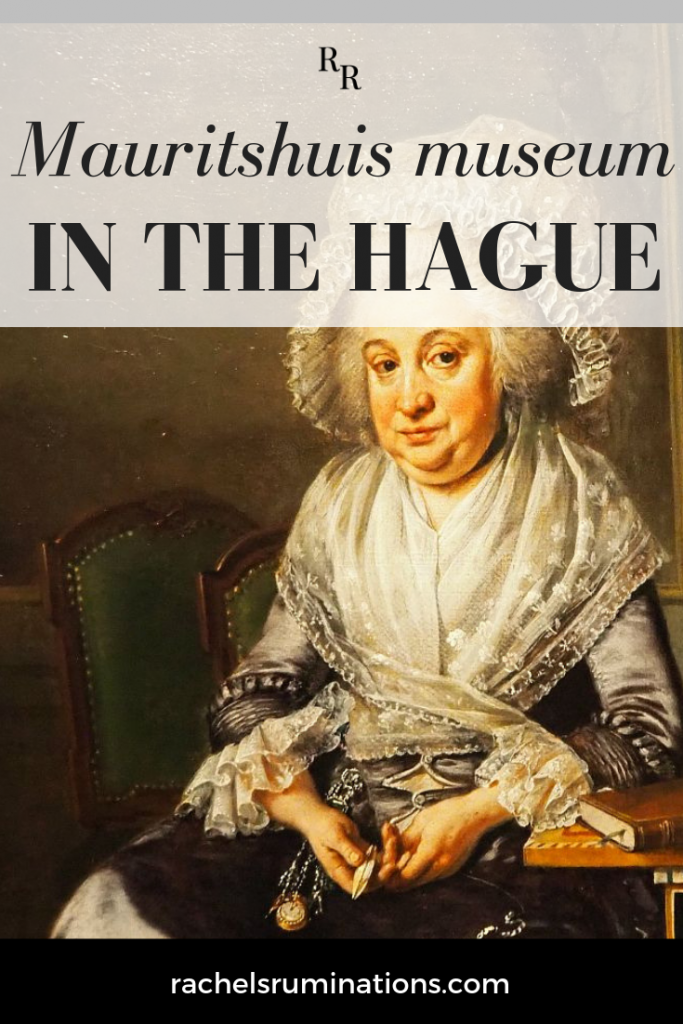

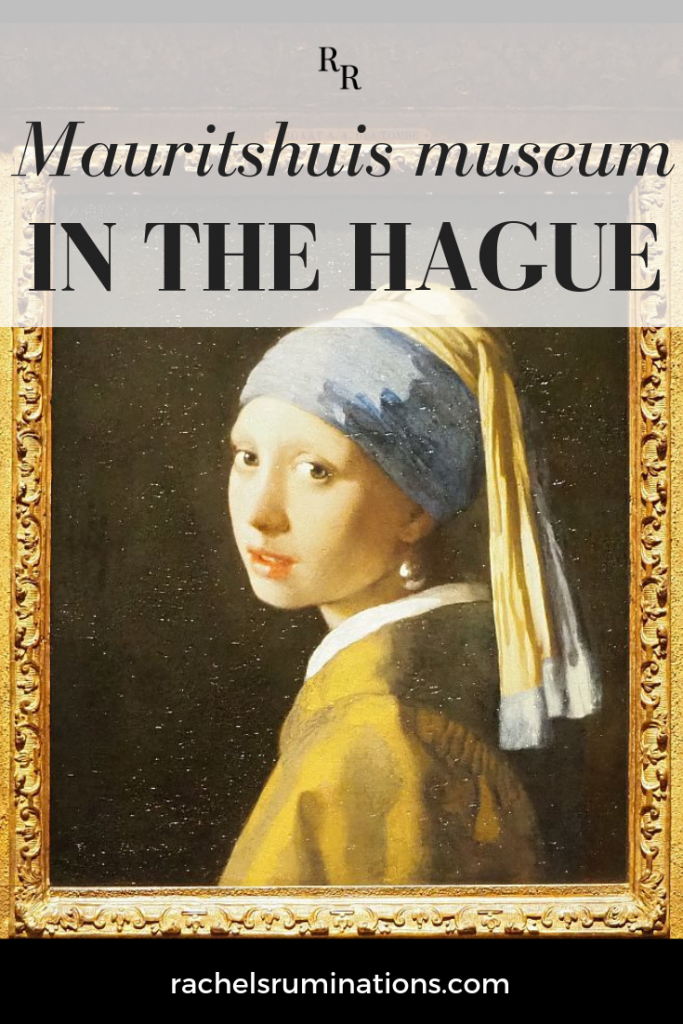

My initial interest in visiting Mauritshuis, an art museum in the Hague (Den Haag), had to do with one single painting: Girl with a Pearl Earring, by Johannes Vermeer, painted in about 1665. But this outstanding little Den Haag museum has many more gems of Golden Age painting.

A disclosure: This is a sponsored post: Mauritshuis Museum was kind enough to give me free admission. Nevertheless, as always, all opinions are my own.

Another disclosure: This article contains affiliate links. If you click on one of them and make a purchase, I’ll receive a small commission. This will not affect your price.

Mauritshuis Den Haag museum

Mauritshuis is named after Johan Maurits, who built this city mansion in the Hague in the 17th century. It didn’t become an art gallery until the 19th century, with a collection of the finest Dutch and Flemish Golden Age paintings.

This whole little museum just bowled me over, not just Girl with a Pearl Earring. Perhaps it’s in the way the artworks are displayed – many are at eye level – in the mansion’s elegant rooms. The walls have dark wallpaper, and, while the rooms are fairly dim, spotlights add to the chandeliers to make the pictures clearly visible, even the ones behind glass in their frames.

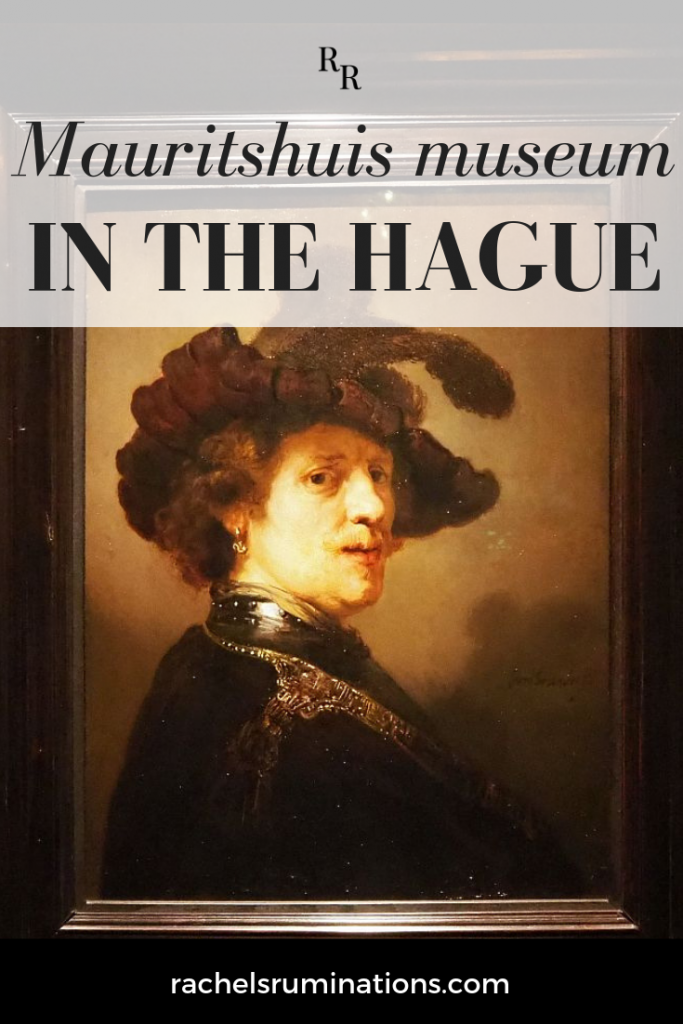

Rembrandts at Mauritshuis art museum in the Hague

Mauritshuis owns eleven Rembrandt paintings and some of them are always on display, including The Anatomy Lesson by Dr Nicolaes Tulp from 1632, a very large, rather gory depiction of a doctor speaking to a group of students wearing ruffs while he dissects the ligaments in a corpse’s arm.

At the moment, though, and until September 15, 2019, the Mauritshuis is showing all of its Rembrandts in honor of the 350th anniversary of Rembrandt’s death. When I say “all,” that means eleven proven Rembrandts and another nine that were thought to be Rembrandts but turned out not to be. Mostly these are products of his students.

The way these twenty paintings are displayed – students’ work amidst the master’s – is an education in itself. Seeing a Rembrandt up close allows a true appreciation of the skill that went into creating the texture of a beard or the play of light on wrinkled skin. I found, as I moved from painting to painting, that I could pinpoint which were done by Rembrandt’s students. They were good, but not quite as accomplished.

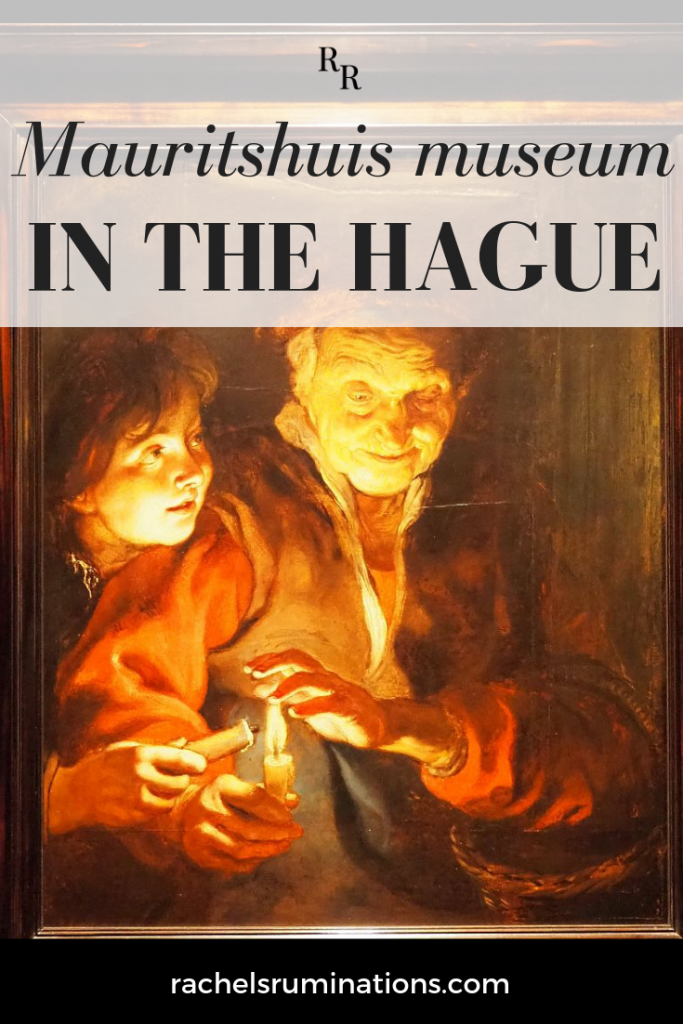

Flemish and Dutch masterpieces at Mauritshuis art gallery

The museum has plenty more to see from the same Golden Age of Dutch and Flemish painting. As I entered each room and recognized paintings, I admit I sometimes exclaimed things like “Oh, wow, I know this one!” out loud, which seemed to amuse my fellow museum visitors.

Jan Steen’s As the Old Pipe, so Sing the Young from 1665, is a wonderfully intricate portrayal of unfettered enjoyment, or, in its context, sinfulness. The details are priceless: the boy smoking a pipe on the right, the relaxed posture of the woman on the left with open collar, getting her wine refilled.

Paulus Potter’s The Bull from 1647 is enormous: life-sized. This allows meticulous detail, down to the flies buzzing around the cattle. The cow sitting under the tree, looking out at the viewer, looks so realistic I felt it might moo at any moment.

Girl with a pearl earring at Mauritshuis

And, of course, Girl with a pearl earring, is indeed breathtaking. Seeing it close-up rather than looking at a photo of it made me appreciate it all the more. Vermeer placed the paint more smoothly than Rembrandt. The girl’s skin is flawless, her lips shine, and so does the pearl. What is she thinking? Why is she dressed in “exotic” clothing?

Girl with a Pearl Earring (1665) by Johannes Vermeer

Mauritshuis, the “Golden Age,” colonialism, and the slave trade

I already mentioned that the name “Mauritshuis” comes from its original owner, Johan Maurits. He spent eight years serving as governor of Dutch Brazil, meaning that his contribution to the growth of the Dutch West India Company’s slave trade is significant. Much of the wealth that the Netherlands amassed during the so-called “Golden Age” came from the slave trade itself or the products of the slave trade, including the sugar plantations of Brazil that Maurits governed.

Mauritshuis is named after Maurits because it was his home, but it retained the name because, historically speaking, he was seen as a benevolent leader. Obviously, given that he supported and profited from the slave trade, this has to be reevaluated.

If this Den Haag museum interests you, you might also like these articles:

- Museum Het Rembrandthuis and Rembrandt’s Life

- Yes, you CAN visit the Rijksmuseum in two hours!

- The Moco Museum in Amsterdam

- Huis Marseille Museum for Photography

Shifting Image: In search of Johan Maurits

Mauritshuis’s temporary exhibit called “Shifting Image – In search of Johan Maurits” allows visitors to do this. Housed in a modern addition to the mansion, the exhibit fills just one room, displaying Golden Age artworks related to the sugar industry, the slave trade and Brazil.

Several of these works are portraits in which a black “servant” is present: an accessory to accentuate the subject’s wealth. Only one painting focuses solely on blacks: a Rembrandt that used to be called Two Moors but has been renamed to Two Africans. A dark, shadowy painting, I couldn’t tell if the two men portrayed were free men living in the Netherlands or if they were slaves. Without their names, we don’t know, but Rembrandt portrayed them as humans in a way that the other paintings in the room, with their decorative black servants, do not.

Frans Post painted a few of the works: he traveled to Brazil and then made his career on selling depictions of exotic landscapes. The ones displayed here show whites and blacks – masters and slaves – as harmonious parts of the landscape.

Several more works show portraits or still-life studies. At first glance, I didn’t see the connection, but reading the extensive notes to the exhibition helped me see that these all represent colonialism. The objects in the still-lifes and the clothing and surroundings of the portraits all demonstrate the 17th-century Dutch fascination with the exotic. Girl by a High Chair (1640) by Govert Flinck shows lumps of sugar on her high chair, something that likely came from Brazil, the product of slave labor. In Flowers in a Wan-Li Vase, with Shells (1640-50) by Balthasar van der Ast, the vase must have been imported, part of the Dutch East India Company’s worldwide trading empire.

The Prince Willem V Gallery

The collection on display in the Mauritshuis is comprehensive and uncluttered. However, there is more to the Mauritshuis’s collection, which you can see a couple of blocks away at the Prince Willem V Gallery.

This gallery is just the opposite in terms of how the artworks are displayed. Where at the villa I could view most of the works straight on with a sign next to each giving the title, date and artist, at the Prince Willem V Gallery, I was immediately overwhelmed.

The gallery is just one small entrance hall and one long, narrow hall, purpose-built 1n 1774 to house these artworks. The hall has a high ceiling with three large, bright chandeliers down the center.

The problem I had wasn’t the number of paintings – the gallery holds about 150 – it was how they were displayed. Apparently, when Prince Willem V of Oranje-Nassau had the room built, he hung the paintings in just this way: absolutely covering the walls. The point was to show off his extensive collection.

That means that as many as six paintings, depending on their size, hang one above the other. Which in turn means that some of them are barely visible. Either they’re just too high up on the wall, or the chandeliers cast a shine, obscuring the picture.

No signs identify the pictures. Instead, a booklet shows a drawing of each wall, with a number on each painting. Below the drawing, you can find the number to see who painted it, the year and the title. Without that booklet, I never would have known that that painting up high is a Rubens.

I did identify a Jan Steen just by subject and style (another version of As the Old Pipe, so Sing the Young), but that was also lower on the wall.

Clearly Prince Willem V Gallery is kept this way so that visitors can see how paintings were displayed in Prince Willem’s time. It’s a shame, though, that as a result so many valuable paintings are so hard to view. And it makes such a contrast to the considered arrangement in the Mauritshuis itself.

If you like what I do on this website, consider subscribing to my monthly newsletter. You can sign up by filling in this form. I promise never to spam you or give your email address to anyone.

My review of Mauritshuis

I’m not a particularly patient person. I tend to avoid large museums and I can’t handle more than about two hours in them; I just can’t focus that long. At the same time, I do like to see great art. The Mauritshuis was perfect for me.

If you just want to see the height of Dutch and Flemish 17th-century paintings – the best of the best – go to the Mauritshuis. If you want to see a much wider range of periods and styles and places, it’s not the right museum for you. In that case, go to the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, but make sure you have a lot more time to see it.

One thing I would suggest, if you have more time and patience than I do – I needed to go catch a train – is that, after viewing the exhibition about Johan Maurits, you return to main rooms to look again at what is visible in the still-lifes and portraits. I suspect that with an increased awareness of the 17th century love of the exotic, you’ll be able to spot more examples of the results of colonialism showing up in the paintings.

As for the Prince Willem V Gallery, I’d recommend going, if only to get a look at how the 18th century elite displayed artwork. It might be fun, too, to try to see how many you can identify without looking them up.

If you’ve enjoyed looking at the photos of the artworks, here are some of my favorites:

Visitor information for Mauritshuis art museum in the Hague

Directions to Mauritshuis: Plein 29 in the Hague (Den Haag), a 10-minute walk from Central Station. If you’re traveling straight from Schiphol, take the train from the station under the airport (usually platform 5 or 6, but check the signs) and get off at Den Haag Central Station. The train trip will take just under 40 minutes. From Amsterdam Central Station the train will take about an hour to Den Haag Central Station.

Another option would be to take a tour of the Hague that includes pick-up at your hotel (150 kilometer limit), a tour of Mauritshuis and a walking tour of the Hague.

Hours and prices: Mauritshuis is open Monday 13-18:00; Tuesday, Wednesday, Saturday and Sunday 10-18:00; and Thursday 10-20:00. Buy your tickets ahead.

Audio tour: You can download the Mauritshuis tour from GooglePlay or the AppStore for free. It has information on all the paintings in English and Dutch, and highlights in several other languages. There’s also a separate tour aimed at children starting at 13 years old. Don’t forget to bring earphones! If you prefer, you can rent the tour at the museum.

Please share this article in any way you prefer! The images below are formatted for Pinterest.

Thank you Rachel! I am in the Hague next Monday and after reading this, I’m really

excited to visit the museum on Monday afternoon! Kate xx

Enjoy!