UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Lebanon

One of the reasons I returned to Lebanon recently had to do with a particular UNESCO site called Baalbek. It was such an amazing site that, when the opportunity arose to return to Lebanon, I jumped at the chance. I wanted to see it again, and my husband wanted to see what I had raved so much about after my last trip. But there are, in fact, four other UNESCO World Heritage sites in Lebanon, and we were able to visit all of them on this visit.

Disclosure: We toured Lebanon as guests of Tourleb. They have no influence, however, on what I write here.

What follows is a list of all five UNESCO sites:

1. Baalbek

If there’s a single UNESCO World Heritage site in Lebanon that you should see, it’s this one. I wrote about it on my last trip, so I’ll just summarize here:

Baalbek was an important temple site for the ancient Romans, standing on the route between the port city of Tripoli on the Mediterranean and Damascus, in what is now Syria. Originally comprising four large temples, three remain.

The Temple of Venus is largely in ruins, with a small central altar area surrounded by a field full of assorted rubble.

The entrance to the main temple site is less grand than it once was, but the sheer size of the pillars that line to original entrance colonnade give a hint at its former grandeur. Climbing the modern stairs takes you through the main entrance to the hexagonal court, which opens out into what was once the massive Temple of Jupiter. While much of this is in pieces on the ground today, the altars around the sides are partially still standing, and six enormous pillars have been restored. Originally, the row of pillars would have encircled the temple: a truly awe-inspiring sight it must have been.

The highlight, though, is the Temple of Bacchus. It sits on a high pedestal below the Temple of Jupiter. It appears, at least until you enter it, to be largely intact. A rectangular building, it has a colonnade around the outside where the pillars still stand. The pillars even still hold up remaining pieces of roof. The inside of the temple is missing its roof, but again enough of the detailed sculptural elements remain to give an idea of how beautiful this structure must have been.

If you want to read about Baalbek in more detail, see my earlier article.

2. Byblos

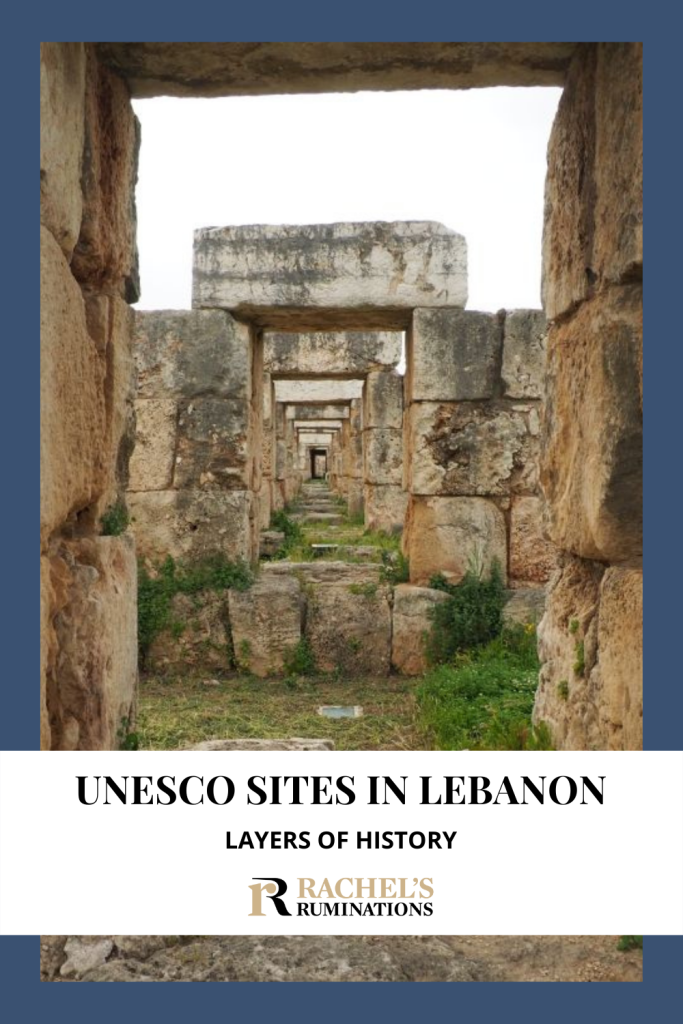

One of the things about the restoration of archeological sites is that the archeologists often discover more than one level of civilization. This is true at pretty much any historical site in Lebanon: they might find traces of the Phoenicians, the Greeks, the Romans, the Byzantines, and so on, all at the same location, since town or temple development is not a static thing. People take what is already on a site and change it or add to it continually through the ages.

Archeologists, then, end up choosing an era to showcase, at least if the location is going to become a tourist destination.

I say all this because this layering of history is most apparent at Byblos. Where Baalbek focuses on the Roman era, its temple site goes back to the Phoenicians. The same goes for Byblos. It’s a UNESCO site because of its importance as a Phoenician city, and the importance of its association with the development of the Phoenician alphabet. This was the first alphabet and influenced many later alphabets.

Yet at the same time, Byblos preserves elements from a whole list of different eras. There are Persian fortifications, for example, and a Roman road as well as a Roman amphitheater, Byzantine-era churches, and a Crusader citadel. The medieval town next door is also part of the site. It was modified over the centuries to include elements of an Ottoman-era city, i.e. mosques, suqs (markets) and khans (hostelries for traveling merchants).

Byblos today

What you see nowadays is a hodgepodge of structures across the site. The most prominent is the Crusader citadel in the center. From the roof of the citadel you can see over the rest of the site. A guide – and yes, I highly recommend you get a guide – can point out remains of temples and housing from the Phoenician period and later periods, a few Roman pillars and the Roman amphitheater, and fortifications from the Phoenician, Persian and Crusader periods.

Byblos archeological site also contains a necropolis: nine large sarcophagi have been found in deep shaft tombs. They date to the middle Bronze Age and show signs of Egyptian influence. You can climb down and see one of them in place: the shafts are vertical, but then the sarcophagi were placed in a side “room” off the vertical shaft. Most of the sarcophagi stand at ground level today.

While you can’t see them at Byblos, more than 100 jars containing human remains have also been excavated there: Phoenician ritual burials dating to 900 BC or earlier. A few of these are on display at the National Museum of Beirut. This museum is well worth a visit to see many finds from the UNESCO World Heritage sites in Lebanon.

3. Tyre

Tyre was once an important Phoenician port city, later conquered by the Greeks and then the Romans. Today it is two sites, but one is mostly submerged. That is where the original town stood, with structures from the Roman to the Crusader periods.

Necropolis

The site that is easy to visit comprises, essentially, two parts. The first is a Roman and Byzantine necropolis. Walking on the remains of a Roman road toward a tall 2nd-century Roman archway, you’ll see dozens and dozens of sarcophagi on either side. Some are huge individual tombs, while others have slots for multiple remains, presumably family tombs. Most of the sarcophagi are fairly worn; not surprising given that they are exposed to the elements. To see the most intricately-carved ones, make sure to go to the National Museum of Beirut.

Hippodrome

Beyond the necropolis and past the towering Roman arch, you’ll reach the remains of an aqueduct – a colonnade of sorts that held the water channel – and an enormous hippodrome. Think Ben Hur and you’ll be able to imagine what this place once was.

Three sections of the stands for spectators survive. You can climb to the top to get a sense of how large the hippodrome once was: it may have been the largest in ancient Rome. The structures that remain around the perimeter of the oval would have once been a passageway under the stands. On event days, sellers of food and other items would set up shop along the passageway to serve the spectators from the seating overhead.

Walk down to the end of the oval and you’ll be able to spot where the turning point was at the end of the track. It was quite a wide track because chariots needed room to turn. There’s also a small ruin of a medieval church with a faded mosaic floor, plunked down in the middle of the racetrack.

4. Anjar

Moving past the Phoenicians and Romans, this UNESCO site is the ruin of a city dating to the 8th century AD: the Umayyad period. It sat on a crossroads – where the Homs to Tiberias route met the Beirut to Damascus route – and illustrates Umayyad town planning. It only lasted less than 50 years before it was defeated and partially destroyed.

Anjar had heavy walls around it with forty towers and a gate in each of the four sides. The city was laid out neatly with four quarters containing the Caliph’s large palace, smaller palaces, a mosque, other living quarters, baths, shops, and so on. A sewer system and water supply were integrated into the town plan.

Today you can wander the city and get a sense of its layout from the low building walls that remain. At one corner some higher walls still stand: palace ruins.

5. Wadi Qadisha (The Holy Valley, a.k.a. Kadisha Valley) and the Forest of the Cedars of God

This UNESCO site in Lebanon is large and it’s hard to know where its boundaries lie. Basically it has two parts: monasteries and forests.

Monasteries

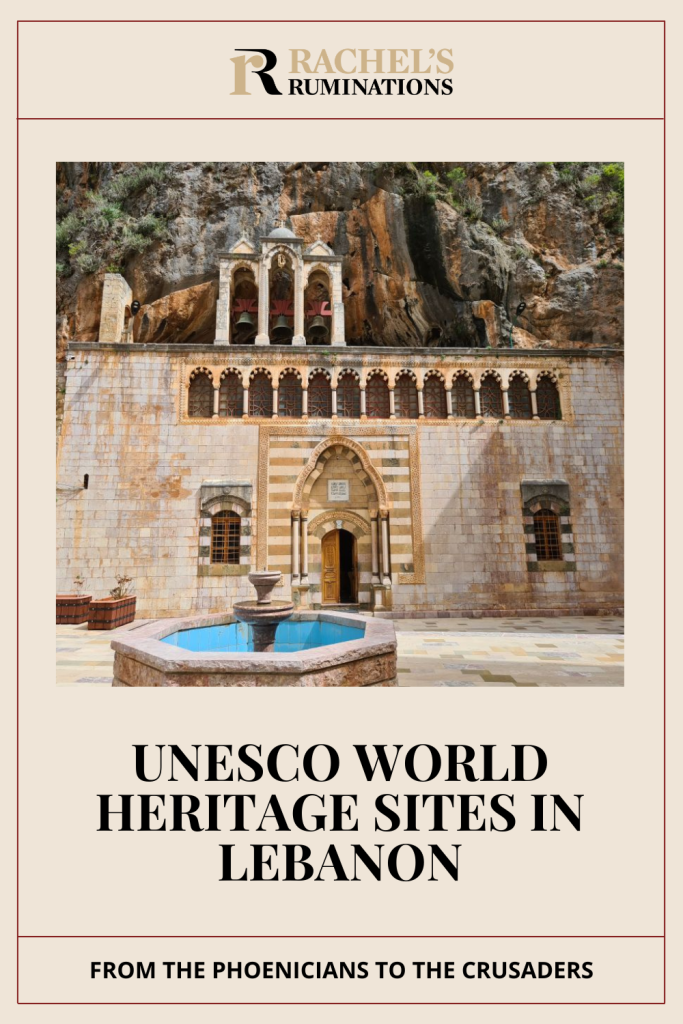

The Qadisha valley, so close to where Christianity was born in what is now Israel, is the site of the very first Christian monasteries.

Christian monks – early Maronites – first settled in the valley seeking solitude. They would move into an isolated cave and perhaps, over time, build a wall and door across the entrance to the cave and also enlarge the cave. Eventually these isolated caves grew and small monastic communities formed. They further refined the caves and decorated them with frescoes. The most important of these today are St. Anthony of Qozhaya, Our Lady of Hauqqa, Qannubin, and Mar Lichaa.

The monks also farmed in order to feed themselves. Over time they terraced the steep hills so that they could grow grain and fruit. These centuries-old terraces still exist, and some are still farmed.

Forests

The Bible mentions cedar wood (Cedrus lebani) 103 times, according to UNESCO. Lebanese cedars even made an appearance in the Epic of Gilgamesh. The wood was much in demand for centuries across the Mediterranean, particularly for shipbuilding. The ancient Egyptians used resin from Cedrus lebani in their mummification process. And according to the Bible, cedars from Lebanon were used in building Solomon’s temple in Jerusalem. Not surprising, then, that their value as a building material led to deforestation.

Today there are still vestiges of cedar forests above the Qadisha valley on Mount Makmel. Efforts to increase the number of cedars of Lebanon are underway. It is no longer legal to cut them, but you can visit them. Be aware, though, that in the winter and into the spring, the snow may make them unreachable.

Which UNESCO World Heritage site in Lebanon should you visit?

As I mentioned above, Baalbek is definitely the one UNESCO site in Lebanon that everyone should visit. I would certainly recommend, though, that you visit with a guide or at least with a knowledgeable driver. It is in the Bekaa Valley near the border with Syria and the area can be dangerous for foreigners. Read my article Lebanon travel tips: What you need to know to avoid nasty surprises! for more details.

(You can also read that article to understand why I’m not giving the usual information about each of these sites: how to get there, opening hours, etc. Rather than using public transportation, such as it is, or renting a car, you should get a guide/driver to visit any of them. I traveled with Tourleb for my whole trip, and highly recommend them for their detailed knowledge of all the sites. Alternatively, you can hire them or another company for day trips.)

Beyond Baalbek, it would depend on your interests. If early Christianity interests you, then go to the Kadisha Valley and see a monastery or two. Byblos covers a number of periods, and the old town there is charming. If you didn’t get enough of the Romans at Baalbek, go see Tyre.

Anjar, while not the most impressive of archeological sights, is set in an interesting town. The French planned and built it in 1939 for a population of refugee Armenians. That story is told here.

If you can only visit one site, make it Baalbek. Then try to fit in an hour or two at the National Museum of Beirut. There, you’ll see a small but high-quality selection of archeological finds from the UNESCO sites in Lebanon as well as other sites. They’re arranged chronologically and well-signposted. Start with the oldest items in the basement. Next go to the top floor to continue the chronological survey, then look at the ground floor last.

My travel recommendations

Planning travel

- Skyscanner is where I always start my flight searches.

- Booking.com is the company I use most for finding accommodations. If you prefer, Expedia offers more or less the same.

- Discover Cars offers an easy way to compare prices from all of the major car-rental companies in one place.

- Use Viator or GetYourGuide to find walking tours, day tours, airport pickups, city cards, tickets and whatever else you need at your destination.

- Bookmundi is great when you’re looking for a longer tour of a few days to a few weeks, private or with a group, pretty much anywhere in the world. Lots of different tour companies list their tours here, so you can comparison shop.

- GetTransfer is the place to book your airport-to-hotel transfers (and vice-versa). It’s so reassuring to have this all set up and paid for ahead of time, rather than having to make decisions after a long, tiring flight!

- Buy a GoCity Pass when you’re planning to do a lot of sightseeing on a city trip. It can save you a lot on admissions to museums and other attractions in big cities like New York and Amsterdam.

- Ferryhopper is a convenient way to book ferries ahead of time. They cover ferry bookings in 33 different countries at last count.

Other travel-related items

- It’s really awkward to have to rely on WIFI when you travel overseas. I’ve tried several e-sim cards, and GigSky’s e-sim was the one that was easiest to activate and use. You buy it through their app and activate it when you need it. Use the code RACHEL10 to get a 10% discount!

- Another option I just recently tried for the first time is a portable wifi modem by WifiCandy. It supports up to 8 devices and you just carry it along in your pocket or bag! If you’re traveling with a family or group, it might end up cheaper to use than an e-sim. Use the code RACHELSRUMINATIONS for a 10% discount.

- I’m a fan of SCOTTeVEST’s jackets and vests because when I wear one, I don’t have to carry a handbag. I feel like all my stuff is safer when I travel because it’s in inside pockets close to my body.

- I use ExpressVPN on my phone and laptop when I travel. It keeps me safe from hackers when I use public or hotel wifi.