All about tower houses in Ireland with tips for visiting

We just got back from a one-month road trip around Ireland – the republic, not Northern Ireland. As we drove, we spotted tower houses – a tall castle-like structure – in many of the towns and villages we passed through, and stopped at some of them to take a look. There are so many tower houses in Ireland that nobody knows quite how many there are. After our trip, that’s not hard to believe. If you travel around Ireland, you just can’t avoid seeing them. A bit of googling and it seems there are probably around 3000 tower houses, many of which still exist, in various stages of repair.

Disclosure: This article contains affiliate links. If you click on one and make a purchase, I will receive a small commission. This will not affect your price.

Before looking at specific ones worth touring, I’ll start by explaining more about them and the things you can look for at any tower house you may visit:

What is a castle?

Ireland’s castles fall into two categories, but they can overlap. What you and I generally think of as a castle includes a central keep and various other buildings inside a fortified wall with guard towers and possibly moats. The Normans introduced this sort of castle into Ireland. Their invasion of England started in 1066, but they moved on to Ireland starting in 1169. They continued to move in in subsequent centuries, gradually assimilating and becoming, more or less, Irish. They are often referred to as the Anglo-Normans, since they went to England first, then invaded Ireland from there.

The Anglo-Normans built castles of the sort they were familiar with. They also fortified their towns with walls and gates to defend them from the Irish chieftains who were liable to attack. This article is not about the Norman castles, but rather about the tower houses that appeared in the following centuries.

So then what is a tower house?

At this point, when the Anglo-Normans settled in Ireland in the Middle Ages, the Irish hadn’t had a High King in centuries. Ireland was a collection of small territories ruled by Gaelic chieftains. These family clans ruled by chieftains didn’t only fight the Anglo-Normans. They also fought each other, and this could often be about something as simple as raiding each other for their cattle. This is why the chieftains built their own version of a castle: a tower house.

As we took tours of various tower houses, they were often presented as a uniquely Gaelic/Irish phenomenon. And indeed, Irish chieftains built many of them. However, in late-medieval Ireland and into the 16th century, both Gaelic chieftains and Anglo-Normans built tower houses all over the country. While the more powerful Anglo-Normans had already built larger-scale castles in cities along with fortifying whole cities with city walls and gates, the less powerful ones who settled in Ireland built simpler tower houses. Starting in 1429, the Anglo-Normans were encouraged particularly when King Henry VI of England – who was trying to assert control over Ireland – offered money to any Anglo-Norman who wanted to build such tower houses around Dublin. They spread from there.

Anyway, tower houses are basically fortified houses. Or you could call them small castles. Most of them are, in the present day, called castles. They’re more or less unique to Ireland, though the Peel Towers of northern England along the Scottish borders as well as some of the tower house castles in Scotland have similarities. As the name suggests, they are single towers, usually square or rectangular in outline, but sometimes cylindrical, built of stone and meant as heavily-defended homes.

To us, there didn’t seem to be much difference between tower houses and castles, except castles tended to be more extended: bigger, with more fortifications. A castle’s keep might resemble a tower house, but there were other buildings inside the fortification as well. Generally a tower house stood alone, with all the household functions inside that single building.

Compare rental car prices at Dublin Airport or Cork Airport.

If driving yourself around Ireland doesn’t sound like your idea of a good time, think about taking a multi-day tour. You can compare tours offered by a range of companies here or click on the images below:

Things to look out for at an Irish tower house

If you road-trip around Ireland, as we did, you’ll spot numerous tall tower houses. Even if they’re not accessible or in ruins and abandoned, there are a lot of details you can spot even from the outside. If they’re open for touring, you’ll see even more.

Defensive elements

All tower houses have a range of defensive elements. The intention was not to hold off large organized armies; it was about smaller attacks by neighboring chieftains.

External wall

Some tower houses had external perimeter walls, called bawn walls in Ireland; but some didn’t. They would be stone-built walls defending an area (a bawn) around the tower house. The wall often included guard towers at the corners and a curtain wall between the watchtowers. There was likely a wall walk or bawn wall parapet along the top of the perimeter wall. This allowed defending guards to move along it. On a day-to-day basis, the residents might use the bawn itself as a place to bring livestock at night, to protect their cattle or sheep from raids by neighboring clans.

Tower house walls

The walls of the tower house itself were defensive too. They are of stone and extremely thick – generally two or more meters at the bottom, wider than near the roof. This “base batter” was partly just necessary for the stability of the building, but it’s also a defensive feature. Look upward to the top of the tower house. It may have machicolations that extend outside the wall. These have open holes that allow defenders above to drop things down on attackers: things like hot tar or boiling oil or just plain rocks. Whatever they drop will hit the lower part of the wall that curves out a bit. This will splash the oil or shatter the rocks, causing more damage at the attackers’ head height. The clearest example I can show you is Athenry Castle – you can find its photo below.

Another common feature is a small machicolation just above the entrance doorway – a sort of window jutting outward. Look up at it and you’ll likely see holes on the underneath. This machicolation is directly above the entrance specifically to defend against attackers trying to get in.

You might also see similar constructions on the corners of the tower house (see photo above of Augnanure Castle). These bartizans allowed guardsmen to keep an eye on two sides of the tower house at once.

The walls would have originally been white with a lime mortar spread over the stones. We didn’t see any on our trip that were still white on the outside. I think the purpose of the white coating was to make this small castle stand out: a declaration of power.

Parapets

If the top of the tower house is intact, you’ll see a parapet – a low wall around the top – with crenellations as you look at the tower from below. These allowed guards stationed on the roof to have some amount of protection in case of attack. Unfortunately, visitors today are usually not allowed up on the roof.

The crenellations in Ireland are often in a stepped form, as is visible in the photo of Aughnanure Castle above. This distinguishes them from the typical Anglo type, where the crenellations are all the same height.

The front door

While today the doors on tower houses are simpler, generally these doors were heavy oak, and often double-layered oak. They would have heavy iron studs through them, and these would sometimes even be pointy. Or in front of the oaken door there would be an iron “yett” – an iron grill set into the doorway so that it could not be pried open from outside.

Murder holes

If you have the opportunity to tour an Irish castle or tower house, make sure to look up when you enter the building. You’re likely to see a hole above your head. Nowadays it’ll be blocked with a grate or concrete. The idea of a murder hole is that if attackers have managed to get by your outer defensive walls and your heavy oaken door, complete with iron spikes or yett, you’ll still be able to stop them here in the entryway. Guards in the room above the entryway can either shoot downwards with crossbows, stab downwards with spears, or drop rocks or hot tar on the attackers’ heads.

Peepholes

You may also notice, inside the entrance lobby, one or more holes to neighboring rooms or next to the door leading out. This allowed those inside to check out who was coming in before opening doors. Often, inside the entryway, the door to the right leads to a small chamber used as a guard room and the door to the left leads to the spiral stairs to the upper floors.

Stairways

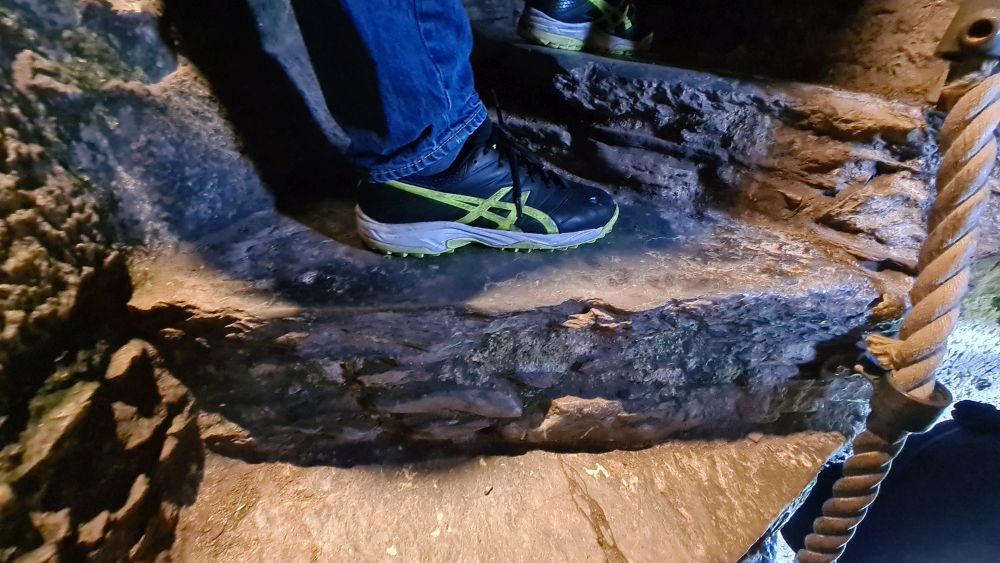

In some tower houses that are now open to the public, you might be able to climb the original staircase. A single spiral staircase in one corner of the building would connect all of the floors. This staircase got narrower as it rose and, while the one you climb when you tour the place might have a handrail of some sort, it didn’t then.

These stairways were also defensive features. They were made narrow and uneven on purpose. Watch your step, because some steps will be higher than others. That was on purpose, so that if attackers got through the oaken door and past the murder hole and tried to climb the stairs, they’d be at a distinct disadvantage. They’d have to climb one at a time because the stairs were so narrow, and they might trip in their hurry on the uneven stairs.

The stairs also rise in a clockwise direction. Since most people are right handed, this meant attackers going up operated at a disadvantage. Their right arms had distinctly less room to swing a knife, axe or sword than the right arms of defenders above.

The intention of all these defensive measures was to stop rivals from taking over the tower house. However, more often than not, they weren’t actually trying to take over the place. Many attacks were raids to steal livestock. This is why chieftains often built a wall outside the tower house; it allowed them to bring at least some of their livestock inside the walls for protection.

Tower houses ceased to be much use in terms of defense when weapons like muskets and cannons came into play. Each tower house’s fate depended on who owned it – or who the ownership passed to. Some saw huge changes, especially with the ascendency of British rule over Ireland, when prominent Englishmen gained ownership and began to add wings to tower houses or add conveniences like indoor fireplaces and larger windows.

Some, on the other hand, were abandoned and left to decay.

Others stood empty until the 19th-century love for everything medieval led wealthy enthusiasts to fix them up. This usually meant changing them considerably to both update them with things like indoor plumbing and to match modern ideas about how medieval castles should look. They added things like larger, exaggerated parapets to the top of the house and Victorian furnishings inside.

Some families held on to them into the mid-20th century, then handed them over to the Office of Public Works (OPW), presumably because upkeep became too much.

How tower houses were organized

Typical tower houses had entrances right at the ground floor, which was used for storage. Some, though, had their main entrance up higher, above the storage level, with a wooden stairway climbing to it. In case of attack, the occupants could destroy the stairway and be safe upstairs.

Most tower houses were between four and six storeys tall. One of the upper floors would be a great hall or banqueting hall, usually on the top floor. Here, the resident chieftain received visitors and carried out his clan business.

One or two floors would be for household use: a main room would provide living and working space and perhaps also serve as a kitchen. In smaller tower houses, it might also be where the household slept. That could mean everyone sleeping on the floor together, including the chieftain, his family and his servants.

Hired guards might sleep elsewhere – places like the ground floor, the watchtowers, or the defensive spaces at the top of the house. Or there would be a loft of sorts – an added story on the main hall or one of the other floors of the tower. The servants and/or guards could reach it by a ladder and all slept on the floor together.

Most tower houses had a vaulted ceiling over the ground floor, and usually another one up higher, while the floors between them were wooden, supported by wooden beams resting on projecting corbels on the walls. The stone floors, especially that bottom one, were important in case of fire. A wooden floor might burn, but the whole tower would not collapse because the stone floors wouldn’t burn. Because of these vaulted stone levels, the banqueting hall, whether it was on the first floor or the very top floor, would have a stone floor.

I’ve written about lots of different castles located in lots of different countries. Check them out if you like them as much as I do!

More interesting details to notice

Garderobes

A garderobe is the medieval version of a bathroom. A small room on the outer wall of the house would have an opening in the floor. At the time, there’d be a wooden seat above that. The waste would fall down the chute under the seat: apparently they used moss for toilet paper. On some tower houses the chute led to the exterior of the building, but in others it was a closed chute so that the wastes would pile up in a limited space at the bottom. They generally tried to add garderobes on the downwind side of the building, for obvious reasons.

As you can imagine, this would be pretty smelly. The wastes produced ammonia, and that ammonia would rise up the chute. That’s why the bathroom is called a “garderobe,” which is from the French and designates a place to store clothing. In these times when baths only happened perhaps once or twice a year, people constantly had to deal with fleas and lice. They would hang their clothing in the garderobe and, in theory at least, the ammonia would eliminate the bugs. Whether that actually worked, I don’t know.

Even when you can’t tour a tower house, you might be able to spot the garderobes on the outside of the building. They’re generally square or rectangular openings, unlike the vertical arrow slits or vertical windows added later.

Corbels

Look for corbels in some of the higher-ceilinged rooms. These are stone projections sticking out of the wall that show that an additional floor was once here – often taller stories were divided in two to make more floor space, especially bedroom space.

Fireplaces

The only way to heat tower houses was with fire, and at first the fire would have been in the center of one of the stone floors. Later, fireplaces were added in the bigger rooms and used for cooking as well. Notice that on the floors used for bedrooms, there are often no fireplaces. Life was not easy for those living in tower houses, even if they were wealthy. They mostly slept on the floor on piles of rushes or straw. The wealthiest might have had a bed – with straw mattress – and that could be a bit warmer with the use of draperies around it.

Besides being cold, these rooms would have been dark without a fireplace. Candles were expensive, so for everyday use a rush light would be used: the central pith of a rush, dipped in animal fats, would burn for about fifteen minutes to a half-hour. It would be placed in a special holder to stop it from falling into the rushes on the floor and starting a fire.

Windows

When they were first built, tower houses had very few and very small windows. There would be arrow slits – also called gun loops, since they switched to guns later – so their guards could shoot outward without attackers outside hitting them. The photo above from Athenry Castle shows one of them.

The top floors might have a few bigger windows to let in some light, but glass was pricey. Often these upper windows – which you can spot from the ground outside – are in the form of a “double ogee head” window. This means two narrow vertical windows with arched tops, set very close together. Of course, tower houses that were inhabited for longer were altered over the centuries, with more windows added and other efforts to make the space more comfortable. Later generations added more fireplaces and divided rooms up as well.

You may notice that some windows have a sort of half-pipe-shaped form outside the window and a sunken cut in the windowsill at the bottom. This was to allow the inhabitants to discard waste like dirty dish water.

The inside walls

Because it was so dark in tower houses, originally they would have been smeared with a white lime mixture that served as a sort of paint. All of the inside walls and also the outside would have been white, and that layer would have been reapplied on a yearly basis. A few of the tower houses that are open for tours have painted walls white inside, and it does give a better impression of what it was like. The layer of white makes them brighter and somehow more homey.

Use the map below to find accommodations. While it’s centered on Dublin, just drag it to wherever you need to find a place to stay:

The stairs

I already pointed out how the stairs were uneven and narrow and had no handrails. Servants, however, had to climb up and down these stairs every day. They carried water, for example, from a well for cooking. They carried wood for the fires. Notice, as you climb or descend, the inside column – not really a column but the place where the narrow ends of the stairs come together. It’s smooth. What I mean is that the centuries of servants climbing these stairs without a handrail would have clutched that point to steady themselves as they moved and that action, over centuries, has smoothed the corners.

Ceilings

When you look up at a stone ceiling, you might notice a pattern of small lines. These are traces from building the tower house.

Builders would start by putting up a wooden scaffold. They covered the scaffold with a wicker mat, then covered the mat with a layer of mortar. The stone ceiling would be constructed on top of that. Once they had finished the ceiling, they removed the scaffold, but might not remove the wicker mat. Instead, they’d finish the ceiling with the same lime mixture they used on the walls, holding the rush mat in place and letting its pattern of lines show through. Or, alternatively, the mat would be removed, leaving the pattern in the mortar.

Floors

The floors were stone or wood, depending on which level they were on. In the living spaces rushes or straw covered the floors; they’d be replaced periodically with a fresh layer. Notice as you step into the rooms that the threshold or sill underfoot is a bit high. Watch your step so you don’t trip! That sill was intentional: it held the rushes in place so that people walking in or out of the rooms wouldn’t end up kicking them down the stairs.

Tower houses worth seeing

As I mentioned above, there are thousands of tower houses sprinkled across Ireland. Some are in ruins, some are in private hands, while some are operated by the OPW and open for tours.

Speaking of the OPW, if you’re going to be visiting lots of historical sites – not just tower houses – it might be worth getting a yearly pass from the first one you visit. For 40 euros (30 if you’re a senior), you get free admission to all OPW sites for a year. Since most of the minor sites cost about five euros, it’s worth doing if you’re expecting to see eight sights or more. The more popular sites, like Brú na Bóinne, can cost considerably more. Brú na Bóinne’s admission fee is 18 euros.

We visited the ones we’d read about in a guidebook ahead of time, plus we stopped at a few ruins we spotted along the way. Here are the ones I felt were most worth visiting, in alphabetical order:

Athenry Castle in County Galway

Athenry Castle is a 13th-century Norman tower house, still standing along with some of its surrounding walls. It’s not a particularly tall tower house with a rather short square tower. There’s a storage level at the ground floor, living and working quarters above. In this case, it had a stairway up to the main entrance, making it harder to attack. The entrance leads into a great hall, and above that was only one more original storey, though one was added above that later.

The reason I include this rather simple tower house is that are some subtle architectural details that are interesting about Athenry Castle. The Norman owner must have been quite high-status. He had the wealth to hire stonemasons who more normally worked on churches and abbeys. Some subtle but elegant carvings frame the doors and windows of the great hall. Otherwise there’s not much more to see here but big empty rooms.

Athenry Castle is in the town of Athenry in County Galway, about a half-hour east of Galway City. It is operated by the OPW and is only open from March to November. See the OPW website for exact dates, hours and prices.

Aughnanure Castle in County Galway

I think this 16th-century tower house may have been our favorite. Built by the powerful O’Flaherty family, it has all the hallmarks of the classic tower house: a square, single tower, with all the requisite defensive elements, as well as some interesting and unusual details. External halls were sometimes added to tower houses, including this one. In this case it was a new banqueting hall at ground level whose main function was to impress. Not much of it still stands now; a river undercut the building gradually until it collapsed. However, a hint of its former grandeur is visible in the windows of the single wall that remains – fine carvings in the arches betray enough wealth to spend on extras.

This tower house is also unusual in that it had extra defensive structures: a double bawn. A small round watchtower still stands, with an intact corbelled roof, an unusual feature. “Corbelled” means it’s made of concentric layered stones, each level projecting further out than the one below.

This castle is operated by the OPW. They offer an excellent tour in the form of a walk around the grounds pointing out aspects of the castle, its strategic location, the social structures surrounding those who lived in the house, and so on. Then we were free to explore the unfurnished interior on our own.

Augnanure Castle is a few kilometers outside the town of Oughterard in County Galway and about a half-hour’s drive north from Galway City. It is operated by the OPW and is only open from March to November. See the OPW website for exact dates, hours and prices.

This day tour includes Augnanure Castle, Connemara and a sheepdog show as well!

Blarney Castle in County Cork

You’ve probably heard of Blarney Castle, home to the famous Blarney Stone. It’s probably one of the most famous castles in the world. Supposedly, if you kiss the Blarney Stone – which people do upside-down, for some reason – you’ll get the gift of eloquence in speech. If you ask me, you’re more likely to get the gift of a viral infection. You can read about several Blarney Stone legends here.

Blarney Castle, besides being the most famous of Ireland’s castles, is more impressive than most tower houses. That’s because it was built in two stages, so it looks like originally it was a traditional tower house similar to so many others in Ireland. The second stage doubled its size, making the “tower” much more substantial, and also a couple of stories taller than most. Not only that, but it sits on a rocky outcropping, which adds to its height.

The original tower dates to the 15th century, replacing an earlier one that had been destroyed. The second one was added in the 16th century.

As I expected, this castle was crowded. We waited about an hour and a half in line to get inside the castle. Visitors are led along a one-way route, much of it up and then down very narrow spiral staircases, so it moves extremely slowly through the building. This took us about another 40 minutes. The route takes everyone to the Blarney Stone, whether you want to kiss it or not. I didn’t. No one was cleaning it between people, so I expect a lot of people get Covid after their visit.

(As a matter of fact, we visited Blarney Castle the day before departing for home, then came down with Covid within a week or so of returning home. Now that I think about it, I realize we could have easily caught it in that 40 minutes of so slowly working our way up and down narrow spiral staircases so close to so many other people. We didn’t need to kiss the stone to catch it.)

Nevertheless, the castle is interesting, and informational signs in each room explain what the room was used for and point out interesting details. It’s also the only castle we visited where we could access the roof. The views are very pretty from there – most people just focus on the stone-kissing, which happens on the roof.

This castle costs a lot to enter – it’s not OPW – but it does have other things to see. Extensive gardens surround it, and some of them are unusual: a poison garden, for example, and a “jungle.” You can also see the Scottish-Baronial-style Blarney House, dating to the 19th century. You can’t go inside, though, because the owners (since the 18th century) still live there.

Because it’s so busy, plan your time well. We joined the line at 11:00, but when we came out 13:10, the line was much shorter. I think many of those waiting were cruise passengers. If that’s so, it would be best to visit Blarney Castle later in the day. And we were there in late September; I assume it would be calmer in the winter.

Many tours visit Blarney Castle, usually from Dublin or Cork.

Blarney Castle is in the village of Blarney, only a few miles northwest of Cork city. It is open all year, but check its website for exact hours and prices.

Dunguaire Castle in County Galway

This restored castle from 1520 sits on an outcropping on Galway Bay directly across from Galway City. I was expecting not to like this tower house. It’s in private hands rather than the OPW and is nowadays a venue for medieval-style banquets, something that strikes me as cringingly touristy. But when they’re not holding a banquet, the castle is open to the public to tour, and we couldn’t resist.

Besides the level that houses the banquets – filled with long tables – the other floors are furnished. I don’t think the furnishings are particularly authentic to the period – I think they’ve been chosen more to fit the medieval atmosphere the operators are trying to create. Nevertheless, the furnishings give a bit of an idea of how the spaces might have been used.

In a wing on the tower – a later addition – we were quite surprised to enter a large room furnished with 20th-century furnishings. Apparently the castle sat, abandoned, for many years until an American bought it in the 20th century and set out to restore it. I guess she lived primarily on this upper floor when she was here.

Dunguaire Castle is near the town of Kinvarra in County Galway, about 40 minutes’ drive south around the bay from Galway City. It is open for tours and medieval banquets only in the summer season. See its website for more specific information.

This tower house is often a stop on tours from Dublin or Galway to the Cliffs of Moher.

Ross Castle in County Kerry

Ross Castle is inside Killarney National Park and dates to the 14th or 15th century. Another property of the OPW, this castle ruin has been restored to some extent, with new roofs allowing some of the rooms to be white-plastered and furnished, though not with original furnishings.

What I liked about this castle was that, while you can only explore it as part of a tour, that tour is very informative, pointing out details you might never notice otherwise. It gave us a real sense of how people in this sort of castle lived on a day-to-day basis. While you wait for the tour, get more information from the exhibition room just past the ticket desk.

We visited on a rainy day and didn’t see much of the rest of the park, though it looks pretty. What we did see was Muckross Abbey, about 10 minutes’ drive away, which is definitely worth visiting. Besides tower houses, we visited lots of ruined abbeys on this trip, and this was probably our favorite.

A variety of day tours explore Killarney National Park and Ross Castle, many of them involving “jaunting cars,” which are horse-drawn carriages.

Ross Castle is just outside the city of Killarney in County Kerry. It is operated by the OPW and is only open from March to November. See the OPW website for exact dates, hours and prices.

Tintern Abbey in County Wexford

This isn’t a castle ruin; it’s an abbey ruin dating to about 1200. However, a tower house was added to it right on top of the transept in the 16th century, after the Dissolution. That’s when Henry VIII ordered all the Catholic monasteries and churches shut down and seized their wealth. Many former churches and abbeys became the property of loyal English nobles after that, and some of them added tower houses.

Tintern Abbey’s tower house is particularly interesting because restorers found and rehung some of its original internal paneling. It gives an idea of how later generations tried to make tower houses more comfortable. You can also see what remains of some interior wattle and daub walls, showing how they were constructed from reeds in a woven pattern.

Tintern Abbey is near the village of Saltmills in County Wexford, a 45-55-minute drive from the city of Waterford. It is operated by the OPW and is only open from March to November. See the OPW website for exact dates, hours and prices.

Tips for visiting tower houses in Ireland

Above I’ve listed what to look for in a tower house as well as a few tower houses I’d recommend. Here are some more general tips to add to the list:

- Take your time and look for the details.

- Watch your step on the stairway, and hold the railing or rope. Don’t rush.

- Keep your eyes on the floor to avoid tripping as you step into rooms from the stairway or into the stairway from the rooms.

- Watch your head as well. Some doorways can be quite low.

- Wear good supportive shoes without heels.

- Don’t forget your camera, but make sure you can hang it around your neck or put it in a bag across your chest or on your back; you may need both hands on the stairs. Binoculars could come in handy too.

- In most tower houses that you can tour, food and drink are not allowed inside. Large bags aren’t advisable either, since the stairways are so narrow.

I saw no tower houses that were wheelchair accessible. The grounds of some of the OPW ones or of Blarney Castle are, so you could at least get a good look from outside, but if you can’t manage the stairs there’s no way to see the inside.

My recommended travel products are below, including WifiCandy’s portable wifi modem. I want to add a tip here about them because they’re based in Ireland: if you’re flying into Dublin airport, you can pick up your rental unit right at the airport, and drop it off there again (or mail it back) at the end of your trip.

One last tip

While these were my favorites, there are undoubtedly lots more that we didn’t see that might be interesting in one way or another. We took to stopping at pretty much every one we passed. Many were in ruins or unreachable on private land, but we could at least take a picture, some of which you can see in the first part of this article. Even the ruins were worth stopping for. They were invariably atmospheric – standing proudly on a rocky outcropping, beside a body of water, or surrounded by green fields and grazing cattle. Some took some walking to get to, but walking in the Irish countryside is an absolute joy.

My tip: when you spot a tower house – and you will! – stop at least long enough to take it in properly. Try to spot some of the details I’ve listed above, but also just take in the rural landscape and try to imagine it as it was built, way back when in the era of the Irish chiefdoms.

If you’ve been to any other tower houses that you’d recommend, I’d love to hear about them. Add a comment below!

My travel recommendations

Planning travel

- Skyscanner is where I always start my flight searches.

- Booking.com is the company I use most for finding accommodations. If you prefer, Expedia offers more or less the same.

- Discover Cars offers an easy way to compare prices from all of the major car-rental companies in one place.

- Use Viator or GetYourGuide to find walking tours, day tours, airport pickups, city cards, tickets and whatever else you need at your destination.

- Bookmundi is great when you’re looking for a longer tour of a few days to a few weeks, private or with a group, pretty much anywhere in the world. Lots of different tour companies list their tours here, so you can comparison shop.

- GetTransfer is the place to book your airport-to-hotel transfers (and vice-versa). It’s so reassuring to have this all set up and paid for ahead of time, rather than having to make decisions after a long, tiring flight!

- Buy a GoCity Pass when you’re planning to do a lot of sightseeing on a city trip. It can save you a lot on admissions to museums and other attractions in big cities like New York and Amsterdam.

- Ferryhopper is a convenient way to book ferries ahead of time. They cover ferry bookings in 33 different countries at last count.

Other travel-related items

- It’s really awkward to have to rely on WIFI when you travel overseas. I’ve tried several e-sim cards, and GigSky’s e-sim was the one that was easiest to activate and use. You buy it through their app and activate it when you need it. Use the code RACHEL10 to get a 10% discount!

- Another option I just recently tried for the first time is a portable wifi modem by WifiCandy. It supports up to 8 devices and you just carry it along in your pocket or bag! If you’re traveling with a family or group, it might end up cheaper to use than an e-sim. Use the code RACHELSRUMINATIONS for a 10% discount.

- I’m a fan of SCOTTeVEST’s jackets and vests because when I wear one, I don’t have to carry a handbag. I feel like all my stuff is safer when I travel because it’s in inside pockets close to my body.

- I use ExpressVPN on my phone and laptop when I travel. It keeps me safe from hackers when I use public or hotel wifi.