Museum Wierdenland: A window into the ancient village mounds of the northern Netherlands

I recently updated my post about things to see and do in the province of Groningen. This province where I live is practically unheard of outside of the Netherlands, yet it has a surprising number of interesting and/or unusual sights and museums within its borders.

Anyway, as I updated all the details on each place, there was one that I realized I’d meant to visit but never did: Museum Wierdenland. So I did.

Disclosure: This article contains affiliate links. Making a purchase through an affiliate link will mean a small commission for this website. This will not affect your price. Privacy policy.

What is a wierde?

First I need to explain what a wierde is. Basically, a wierde is a small hill or mound. That sounds simple, but there’s more to it than that. Groningen province is flat – flat as a pancake. It is also pretty much at sea level. That means that anyone with the audacity to settle here over the last many centuries had to deal with periodic floods from high tides or overflowing rivers or storms.

The first settlers here came from northern Germany in about 550 BC and generally chose the natural levees along the edges of the salt marshes, streams and rivers. They built homes and grazed cattle nearby. Over time, they began to add to the slightly higher banks to make small mounds, big enough for their mud-walled, thatched-roofed house, which included a stable for their livestock. Eventually, neighbors joined these small mounds together, and a village formed, clustered on a single hill. Usually the houses stood in a circle facing each other, with a well in its center for drinking water. Their fields for crops or grazing their livestock were on the lower ground around the village.

In Groningen province, these mounds are called wierden (singular: wierde). In Friesland, they’re terpen (singular: terp).

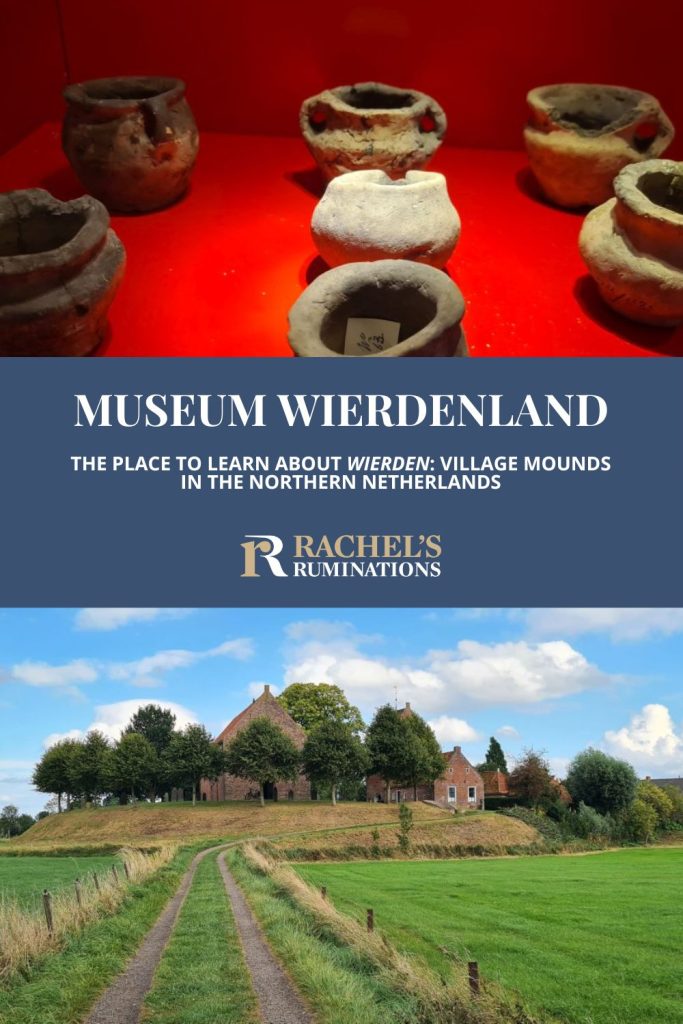

There were hundreds of small villages like this scattered all over the northern provinces, and the wierden offered the villagers some measure of safety during times of flooding. They weren’t very high: perhaps 2-5 meters tall (i.e. 6-15 feet). But it was enough to withstand most flooding that happened.

Wierden in the Middle Ages

And the wierden grew, bit by bit. Partly this was because of sediment left gradually by rivers, streams and flooding. Partly it was through the effort of the villagers to raise at least the center of the mound to offer a higher level of safety when needed.

Starting in about 400 AD, the population declined, though it’s not clear why. Possibly it was just natural migration away, or it may have involved a plague of some sort. The remaining population stayed small in numbers for a few centuries, but new settlers, possibly from England, arrived, as did missionaries spreading Christianity.

With the arrival of Christianity, villagers built churches, which they placed at the center of their villages: in the center of the wierde. Many of these medieval churches, dating to about the 13th century, are still there. The wealthier villagers built brick houses and, eventually, so did everyone else.

Dikes make village mounds unnecessary

Also starting in the Middle Ages, the effort to protect villages by building dikes began, but generally only piecemeal. There was no large-scale dike-building project along the northern coastline until after a huge flood in 1717 killed thousands. That’s when a larger project started, creating a long sea-dike.

Even before 1717, as dikes began to ensure a measure of safety, wealthy landowners moved out of the villages and towns, building sometimes quite grand farmhouses on their farmland. They often stood on smaller mounds a meter or two above the level of their fields, and often they were (and still are) surrounded by a small moat. Sometimes they built smaller houses as well to house their workers. Maintaining the villages’ wierden became less important, and in some places, digging up the mounds became an industry in itself in the 19th century.

If you’re going to be driving around Groningen province, you’ll need a car. Pick one up at Schiphol and avoid the big cities by heading straight to Groningen.

Digging up the mounds for profit and for archeology

Wierden, it seems, contained very fertile soil, after centuries of use (and excretions) by humans and animals, as well as the effects of sedimentation along streams. In the 19th century, companies began to dig up the soil from uninhabited mounds. They sold it to other parts of the country where the land was sandy. Mixed with sandy soil, this improved the harvest.

Next they moved on to inhabited wierden, including the village of Ezinge. You couldn’t just dig up the whole mound, of course, because the houses and church still stood on it. But around the edges, you could buy the land, dig it up, and sell it. (And in some towns, houses were indeed torn down to harvest the land under them.)

And that’s where this museum’s story begins. In the period between World War I and World War II, an extensive archeological excavation began at the little town of Ezinge. The wierde there had been quite deeply cut on one side to harvest the soil. From time to time, the workers had found some interesting artifacts as they dug – not just here but in other towns as well. From 1923 to 1934, Albert van Giffen led a more systematic excavation at Ezinge.

Museum Wierdenland

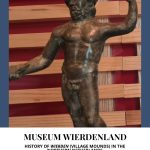

This museum shows the results of that investigation as well as finds from other wierden nearby, all displayed in one large room. A small figurine of Roman origin is the most spectacular. Given that this area was outside the Roman empire’s boundaries, that implies the existence of trade.

A lot of what was found consists of clay pots – not particularly decorative, but rather the sort people used for household storage. They date from anywhere between 800 BC and the Middle Ages. The collection also includes a variety of household or personal objects like farm tools, beads, pins, combs, and needles, but also things for leisure time like dice and a flute. Some of these items may have been used in daily life, but some may have been grave offerings.

Speaking of graves, the museum exhibits include the skeletons of two horses and a dog, excavated from a neighboring village and dating to the 8th century AD. These may have been offerings made as part of an important person’s burial.

And speaking of offerings, the largest farm structure the archeologists found under Ezinge had the skeletons of a horse, a cow and a dog incorporated along the woven side wall of the building. These may have had a ritual purpose.

What turned out to be more interesting to me was the whole history I’ve recounted above. Maps and photographs on the walls illustrate the evolution of wierden in general and Ezinge in particular. Van Giffen’s excavations at Ezinge uncovered the remains of quite a large farmhouse with stalls for livestock. Its walls were still intact to a meter high, with the separate stalls clearly visible and the remains of the poles that supported the roof as well. They partially excavated other similar buildings too. Big black-and-white photos taken while the excavations were underway illustrate the story, and a part of this house is reconstructed here in the museum. Some of the artifacts come from other village mounds, but the story is very similar for all of them.

Visiting Museum Wierdenland

When you arrive, you can start with a 12-minute-long film explaining the origin of village mounds and the history of the Ezinge excavation. Make sure, if you don’t speak Dutch, to let them know that you’d like to see the English version.

At the moment, all of the explanatory labels are in Dutch only, but the museum is being renovated. It will have English signage by the summer of 2026. If you don’t speak Dutch and you visit before then, come prepared with Google Translate on your phone, or a similar app, with the Dutch language already downloaded to it. Nevertheless, you should get the gist of the exhibits just from what you learn from the film and this article.

The exhibits about the wierden are pretty much all in one large room, except for a detailed timeline opposite the reception.

The rest of the small building hosts temporary exhibitions. When we visited, a show of Siemen Dijkstra’s layered woodcut prints was underway. His works are incredibly intricate, looking like photos from a distance but revealing the details on close inspection. Some of the temporary exhibitions are art-related; others look at elements of local history.

Museum Wierdenland: van Swinderenweg 10, Ezinge. Open November-March, Tuesday-Sunday 13:00-17:00, April-October, Tuesday-Sunday 11:00-17:00. Admission: Adults €6, children 6-18 €2.50. Free parking on site. Website.

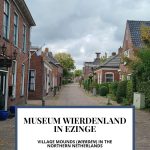

The village of Ezinge

The wierde of Ezinge is right nearby the museum, a short walk away. Ezinge is a lovely town, with a cute main street much like the nearby town of Garnwerd, with its supposedly narrowest street in the Netherlands. This one is a bit wider, but has the same little houses and, like Garnwerd, a very artsy edge. In other words, you’ll see quite a few artists’ homes and studios, often exhibiting their works in their front windows.

The church on the mound is from the 13th century and worth taking a look inside, if it’s open. Like many of the churches in the region, it’s tiny and charming. Restored to its original medieval size and shape, it has small, high windows and classic old tiles on the floor. Originally it had three doors: one for men, one for women, and one for priests. Today it is still in use as a Protestant church.

Notice the original tiny window, low down on the left as you face the altar end of the church. There are several explanations for that tiny window but the most likely, it seems to me, is that lepers could sit outside and observe the services, receiving the Eucharist through the window.

Also notice the 19th-century stone markers in the floor of the church. Only the “stinking rich” were allowed to be buried there. Other graves were just outside until the government banned burials within the town for hygiene reasons.

What is somewhat unusual about this church is that the tower is separate, and a bit older than the church. The building attached to the tower was added later as a school building, though now it’s in use as a meeting hall.

While you’re in the area, take a look at Allersmaborg. This pretty country estate just north of Ezinge village dates to the 14th or 15th century, but with many additions and alterations since then. Today, the University of Groningen owns it and rents it out for meetings and events. You can’t go inside unless you arrange a viewing ahead of time, but I mention it because the grounds, while not huge, are very pretty. There are two concentric, square moats where you can enjoy a pleasant stroll under the trees.

Allersmaborg: Allersmaweg 64, Ezinge, about 4 minutes from Ezinge church by car or 25 minutes’ walk. The grounds are open all the time and free to enter. To arrange a tour or an event, contact info@allersmaborg.nl. Website.

Take a look at my list of things to do in Groningen province; there are bound to be more things that interest you here.

Where to stay

If you’re visiting Ezinge as part of a larger exploration of Groningen province, I’d suggest staying in the capital city of Groningen, a lively college town (and my hometown!). If you prefer to stay out in the countryside, zoom out on the map below to see what’s available:

And if you’ll be spending time in Groningen city, here’s a walking tour of the city so you don’t miss the highlights.

If you visit the museum, come back here and let me know what you think!

My travel recommendations

Planning travel

- Skyscanner is where I always start my flight searches.

- Booking.com is the company I use most for finding accommodations. If you prefer, Expedia offers more or less the same.

- Discover Cars offers an easy way to compare prices from all of the major car-rental companies in one place.

- Use Viator or GetYourGuide to find walking tours, day tours, airport pickups, city cards, tickets and whatever else you need at your destination.

- Bookmundi is great when you’re looking for a longer tour of a few days to a few weeks, private or with a group, pretty much anywhere in the world. Lots of different tour companies list their tours here, so you can comparison shop.

- GetTransfer is the place to book your airport-to-hotel transfers (and vice-versa). It’s so reassuring to have this all set up and paid for ahead of time, rather than having to make decisions after a long, tiring flight!

- Buy a GoCity Pass when you’re planning to do a lot of sightseeing on a city trip. It can save you a lot on admissions to museums and other attractions in big cities like New York and Amsterdam.

- Ferryhopper is a convenient way to book ferries ahead of time. They cover ferry bookings in 33 different countries at last count.

Other travel-related items

- It’s really awkward to have to rely on WIFI when you travel overseas. I’ve tried several e-sim cards, and GigSky’s e-sim was the one that was easiest to activate and use. You buy it through their app and activate it when you need it. Use the code RACHEL10 to get a 10% discount!

- Another option I just recently tried for the first time is a portable wifi modem by WifiCandy. It supports up to 8 devices and you just carry it along in your pocket or bag! If you’re traveling with a family or group, it might end up cheaper to use than an e-sim. Use the code RACHELSRUMINATIONS for a 10% discount.

- I’m a fan of SCOTTeVEST’s jackets and vests because when I wear one, I don’t have to carry a handbag. I feel like all my stuff is safer when I travel because it’s in inside pockets close to my body.

- I use ExpressVPN on my phone and laptop when I travel. It keeps me safe from hackers when I use public or hotel wifi.