Is a Dharavi slum tour a good idea?

Have you ever seen the movie “Slumdog Millionaire”? Privileged Westerners like me are curious about slums like the one in that film. We want to know how people live, how they deal with adversity, how they ended up in a slum, and how we can help. At the same time, we don’t venture on our own into slum areas for fear of being mugged, or worse.

Slum tourism

Recently, a new tourist experience, the “slum tour,” has appeared in various countries, particularly in large cities in Latin American and in India. It offers a way to satisfy the curiosity of tourists, while at the same time enabling them to feel safe. It brings money into the local community, and allows the tourists to learn about conditions in poor countries.

Yet the idea of a “slum tour” has never felt right to me. It reeks of racism and elitism: the slum’s inhabitants in the same position as animals in the zoo. The poor as freaks in a circus.

Besides, I’m much more interested in historical and cultural sights, like Elephanta Caves, a UNESCO World Heritage site, which I visited on this trip as well. Such sites, generally separate from everyday life and catering to tourists, are safely within my comfort zone.

Nevertheless, on my recent visit to Mumbai, a colleague booked a Dharavi slum tour, and I went along. Reality Tours is a non-profit company that uses the tours to fund educational programs for young slum residents. Their charity, called Reality Gives, uses 80% of their tour profits to educate young adults in English, computer skills and life skills. Because it is a non-profit, locally-run tour company, I hoped that it would avoid that animals-in-a-zoo tinge.

I hope that it succeeded. Two things contribute to dispelling that tendency: firstly, the fact that they keep their groups to six or fewer. When I went, I was with only my colleague and our guide, which meant we didn’t crowd the people we encountered on the way.

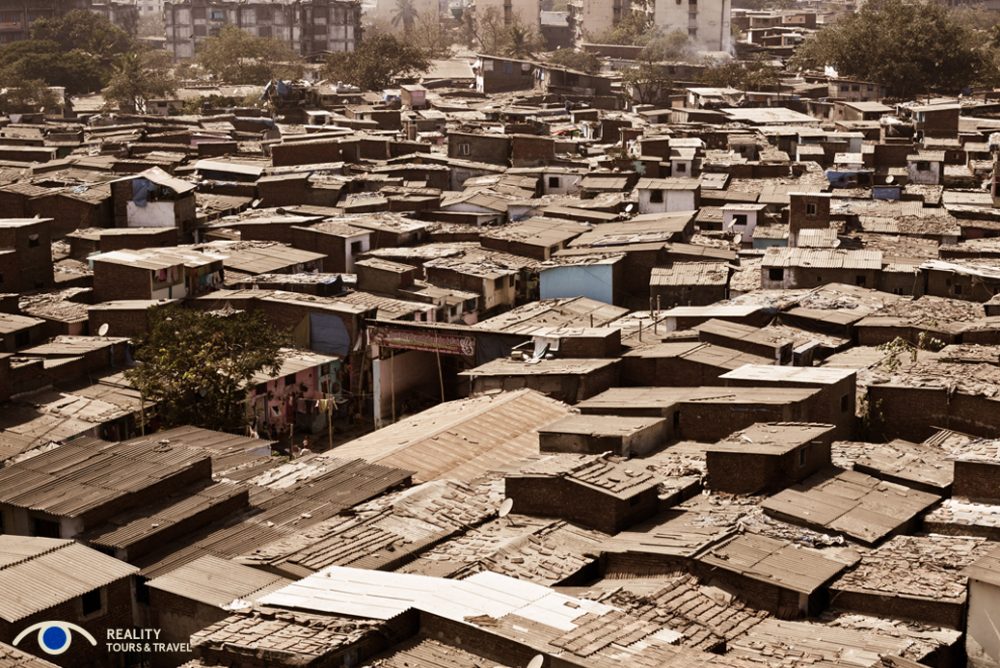

Second, picture-taking is strictly forbidden, except at one point when we climbed up for a rooftop view. While my travel blogger hands were itching to take pictures, forbidding photography shows respect for the dignity and privacy of the people living in the slum.

We had arranged a whole-day tour, starting with a slum tour, followed by stops at more standard Mumbai tourist destinations. I’ll write about those other stops in a separate post.

Note: This is not a sponsored post. My colleague and I paid full price for the day’s tour. I just thought it was an interesting experience and wanted to write about it.

Dharavi slum tour

The slum we visited is called Dharavi. It’s the largest slum in India with over a million inhabitants on about two square kilometers of land. According to our guide, Jitu, who grew up in Dharavi, there are about 2000 slum areas in Mumbai, holding about 42% of Mumbai’s population. “Slumdog Millionaire” was set in Dharavi, and some scenes were filmed there, using local residents as actors and extras.

Streets of Dharavi

As we began the tour, Jitu emphasized that we should not take pictures and that we should stick close to him. This wasn’t out of fear that we would be mugged. He was just worried he’d lose us in the maze we’d be navigating. Once we dove into Dharavi, I could see why he was concerned. While we walked on some full-fledged roads, wide enough for cars, most of the streets were mere alleyways. Some were dirt, while others had paving stones. Many had a gutter down the middle, running with foul-looking bluish-green liquid. Trash lay everywhere: wrappers mostly. Pipes lined the alleys, about the size of a garden hose; I think they were water lines.

These streets are busy, at least mid-morning when we were there. People don’t just use the streets to get from place to place; many work outside. Women squat on the floor inside, rolling chapatis, then lay them on an inverted basket out in the street to dry in the sun. They get paid per kilo. Or they squat just inside their doorways, washing clothing by hand on the floor. Young men cook naan bread in the street over a charcoal fire, again a form of piecework. Small stalls, no more than a narrow counter, sell low-cost everyday items; sample-sized bags of chewing tobacco seem particularly popular.

Homes in the slum

In the residential districts, most of the buildings lining the alleyways are narrow, perhaps two or three meters across. Sometimes the door is open, and a piece of cloth hangs in front of it, offering some privacy to whoever is inside. The walls are plaster over brick, and often painted. In other words, the buildings are more solid than I expected; these are not shanties or shacks.

The houses are multi-story: mostly two or three floors in total, with steep metal ladders leading from the street to the upper floors. Jitu told us that a separate family lives in each room. I caught a glimpse inside a few, and they are extremely small for a whole family: perhaps six to twelve square meters. At the same time, they are neat and clean. Upstairs, iron grills extend outward from many of the windows, offering space for window gardens; people do their best to beautify their homes.

When I commented to Jitu that these did not seem like shanties, he told me “They’re not shanties.” Pointing down the street, he added, “But those over there are.” The buildings he pointed to had corrugated iron siding rather than brick.

Jitu told us that in 1995, instead of clearing out the slum, the government decided to give each bit of land to the people who had settled on it. In other words, people now own this land. Or, rather, they own it if they lived there in 1995. Nowadays, many residents rent their rooms from the owners, who have moved up and out of the slums. The buildings that Jitu called shanties date from after 1995, and are illegal. Whoever put them there doesn’t spend the money to build something permanent and solid because the government could evict them.

At the same time, Jitu said, this is still called a slum. The distinction is that it’s a slum as long as people don’t have toilet facilities in their houses. None of these do, even those that predate 1995. There simply isn’t room, even if they could afford to install a bathroom and a suitable sewer system was available. Water is available, but it only flows about an hour a day, and inhabitants make sure to fill up containers when the water is on. It isn’t safe to drink, so drinking water has to be boiled first. Communal toilet blocks inadequately serve the inhabitants: over a thousand people per toilet. Women have a toilet block where they can take private showers. Men wash at home out of buckets.

Industry

Our general impression was of a place that is teeming with enterprise: people making a living, trying to get ahead in whatever way they can. Jitu took us through an industrial district of Dharavi, where one of the biggest industries is plastics recycling. We looked into a workshop where a row of men sat on the floor, sorting plastic trash into piles. Nearby is a machine that shreds the separated plastics into small pieces. In another workshop nearby, workers wash the shredded bits. The end product in the slum is the shredded plastic: the companies sell it by weight to businesses elsewhere, which in turn process it into recycled-plastic products.

The people who work in this neighborhood are often migrants from the countryside, usually young men. They live together in the upper floors of their workplace. The owners of the small factories are former slum dwellers who started these businesses inside their own homes. When they moved out to better neighborhoods, their former homes became factories.

We passed a number of other manufacturing areas. In one workshop, men build machinery like the shredder we had just seen. We peeked in a doorway at another man who is, according to Jitu, a Muslim who builds wooden shrines for Hindus. We saw a section of the slum devoted to leather processing, though leather tanning is banned from Dharavi these days because it causes too much pollution. Another section overflows with clay pottery, left to dry in the sun. We visited a workshop where workers reprocess the leftover soap from hotels into new bars for other uses.

People of Dharavi slum

As for the people, no one seemed to mind us being there, and most didn’t even look at us as we passed. Perhaps the tours go through often enough to become quite routine. Perhaps they are aware of Reality Tours and the good work it does – Jitu was wearing a Reality Tours tee-shirt – so they don’t mind the tours. I don’t know.

Children were the only ones to approach us, but not to beg. They wanted to say “Hello, how are you?” to us, giggling when we answered.

The children impressed me – as it approached noon they were leaving for school, since the schools run two shifts of lessons. They wore well-kept, clean school uniforms and their hair was neatly combed. I’m in awe of the mothers who can achieve that using only buckets of water and a communal toilet block.

Is a Dharavi slum tour a good idea?

The Dharavi slum tour was fascinating, satisfying our Western curiosity about life in the slums. Jitu is incredibly knowledgeable about Dharavi and Mumbai in general. He didn’t try to exaggerate the problems of the slums, or to downplay them. His insider’s view from his childhood in Dharavi made his discussion very straightforward and matter-of-fact.

I still wonder, though, whether by taking Reality Tour’s Dharavi slum tour, we truly avoided the racism and elitism that I had imagined a slum tour would entail. I’m not sure. What do you think?

I am a co-host of Travel Photo Thursday, along with Jan from Budget Travel Talk, Ruth from Tanama Tales and Nancie from Budget Travelers Sandbox. If you have a travel blog and want to join in, do the following:

- Add your blog to the linkup, using the link below.

- Put a link back to this page onto your blog post.

- Visit at least a few of the other blogs in the linkup, comment on them, share them and enjoy them!

If you don’t have a travel blog yourself, you can still click on any of the blogs below and visit them!

You’ve posed an interesting question, Rachel and I have to admit I too, am intensely curious about the slums. (I thought the movie, “‘Slumdog Millionaire” was as fascinating as it was disturbing.) It seems that Reality Tours has done a good job of explaining and showing the slums of Mumbai in a way so as to educate tourists as well as preserve the dignity of the people who live there. It’s shocking to believe that any cleanliness can be achieved in a place where 1000 people share a toilet or the water runs for only an hour a day. And when you mention the recycling of plastics and hotel soaps, it’s yet another reminder of how wasteful people can be. Thanks for this fascinating and enlightening post! Anita

Glad you liked it! Thanks!

It’s hard not to feel voyeuristic when we are touring anything that feels third world or poor by our standards. Ditto when visiting tribes and other ethnic experiences offered by many tour companies. I think these types of visits are more palatable if the tours are doing some kind of good, and they are kept intimate enough so that busloads aren’t being shipped in to ‘observe’. Still, I think there’s a bit of affluence guilt that contributes to our own feelings of awkwardness here.

Definitely! Good words to describe this: voyeuristic and affluence guilt. I felt similarly when I saw a “demonstration” of Masai dancing in Tanzania.

Rachel, I think this may be the best post you have ever written. I really enjoyed it and learned a lot despite the difficulty of the topic. I was shocked to learn that India has so many slums. I knew there so some, but shocked to learn how many. Very interesting to learn about Dharavi and shocked to learn it has over a million inhabitants on only two square kilometers of land! Growing up in an under-populated region of Canada, that is unimaginable! Like Anita, I found Slumdog Millionaire to be fascinating, yet disturbing.

Thank you! Coming from you, that means a lot to me! Yes, even after walking through the slum, I found it hard to imagine what it would be like to live there.

An interesting question indeed! And I sometimes wonder about taking photos of everyday people on everyday streets in any city we visit. . .how would I feel knowing I was being posted on FB or other media showing how ‘people live’. As for slums, we took a cruise that stopped in Mumbai and one of the tours offered was a slum tour – by a non-profit – the money came back to the slum, but we couldn’t bring ourselves to do it for all the reasons you mentioned. You’ve done a beautiful job on this post – you brought the experience to life and it made me do some thinking – a great combination!

Thank you! I’m still not sure it’s a good idea, even without photos and for a non-profit. Yet how else are they going to raise money?

What a good question. I have never taken a slum tour but, especially in India, I saw a lot of them as I traveled through the country. What amazes me are the smiles and the determination of those living there. You gave your readers a lot to think about. An excellent, excellent article.