History of Little Havana: A Bay of Pigs connection

Little Havana is a very popular tourist destination in Miami, particularly for its colorful murals and the excellent Cuban food and drink. I knew before I visited that it is home to a large and thriving community of Cuban exiles and their families. History fan that I am, though, I wanted to learn about the history of Little Havana on my recent Miami trip.

Disclosure: This article contains affiliate links. If you click on one and book a hotel or a tour, I will receive a small commission. This will not affect your price.

What I found out was that its history is intricately connected to a single event: the 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion.

Little Havana history

The neighborhood hasn’t been Cuban for that long. It wasn’t really until the 1960s that Cubans started settling there in large numbers. There were Cubans living in Miami before this, but only about 10,000. Nowadays there are about a million in the city. Many didn’t stay permanently in those days; there was a lot of back and forth between Cuba and Miami in the decades before the Cuban Revolution. Wealthy Cubans enjoyed Miami as a tourist destination, and some set up businesses in Miami and other Florida cities.

The Cuban Revolution

In the 1950s, Fidel Castro led a revolt against the government of President Batista. He was eventually successful in ousting him in 1958, setting up a Communist government in 1959. Castro’s new government seized all US property in Cuba in 1960, which set the US government firmly against him.

Cuban exodus

Many Cubans opposed this revolution. They were anti-Communist and/or they were in danger because they had collaborated with the Batista government. Some were simply members of the Cuban elite, which put them in danger in Castro’s Cuba. They fled to Miami, though most, at first, had no intention of staying. It was just a place that was nearby, where they could wait till Castro was overthrown.

The Bay of Pigs Invasion

It was in 1961 that a group of Cuban exiles attempted to make this happen. They formed the “Democratic Revolutionary Front” and the American CIA and President Kennedy supported them. It was the height of the Cold War, so the US government couldn’t risk openly attacking Cuba with its military. Given the Soviet Union’s nuclear capabilities and its support for Cuba, a direct US attack on Cuba would lead to war with the USSR.

On April 17, 1961, 1400 fighters for the Democratic Revolutionary Front landed at Cuba’s Bay of Pigs, using equipment supplied by the US. The invasion failed miserably, and 1189 of the exiles were captured and imprisoned while the rest were either killed or escaped to sea. Some of the captives stood trial. Most eventually returned to the US in a negotiated trade for lots of merchandise that Cuba needed.

Use this link to look at accommodation options in Little Havana.

Little Havana and the Bay of Pigs connection

This is the point at which Little Havana really started to grow and thrive. Since the invasion had failed, it was clear that the Cuban exiles were going to be here a while. They settled in more permanently, growing their businesses, especially along Calle Ocho, which became the main drag of Little Havana.

The other way the Bay of Pigs influenced the neighborhood was that many more Cubans left Cuba in the years after that, especially until about 1979. For some, this was a matter of economics: there were more opportunities in capitalist America than in communist Cuba. For others, it was a political decision: they went to the US in search of political freedom or to escape persecution. Either way, Miami became a magnet because of the Cuban community that was already there. At the same time, the US government welcomed them as political refugees.

The Bay of Pigs Museum

It shouldn’t come as a surprise, given how central the Bay of Pigs invasion was to the Cuban community in Miami, that Little Havana is home to a Bay of Pigs Museum.

As museums go, this one is tiny and plain, with lots of photographs and items in glass cases. It seemed to me, though, that despite its name it’s not really a museum; it’s a community center.

The front door leads into a small entrance hall holding a few displays and lots of photos. Directly after that small space is a long space that I can best describe as a conference room. It holds a long, rectangular table and bookshelves filled with books. Beyond that is a large square room, mostly filled with rows of chairs facing a large table opposite. It looked as if the room is used for meetings or presentations. The exhibits about the Bay of Pigs stand along the sides of this room in glass cases.

On the day I visited, a group of elderly men – perhaps 7 or 8 of them – were gathered around the far end of the conference table, discussing something in Spanish. My Spanish is very rusty, and I didn’t feel like I should listen in anyway, so I didn’t even try to get what they were talking about. I smiled, nodded in what I hoped was a respectful gesture, and made a beeline for the larger room in back, walking past the group at the conference table. They looked up briefly but went on with their discussion.

I saw at a glance that the “museum” is really just the glass cabinets around the edge of the room, plus the photos mounted above them. So I stopped and began to inspect the items in the displays. They focused in on the individuals who took part in the invasion – young Cuban exile soldiers called Brigade 2506. The exhibit told about the invasion, but also about the men’s experience in prison in Cuba and about what became of them afterwards.

To learn about another fascinating Miami neighborhood, read Historic Overtown: The place to see Black history in Miami.

And here are some more things to do and see in Miami.

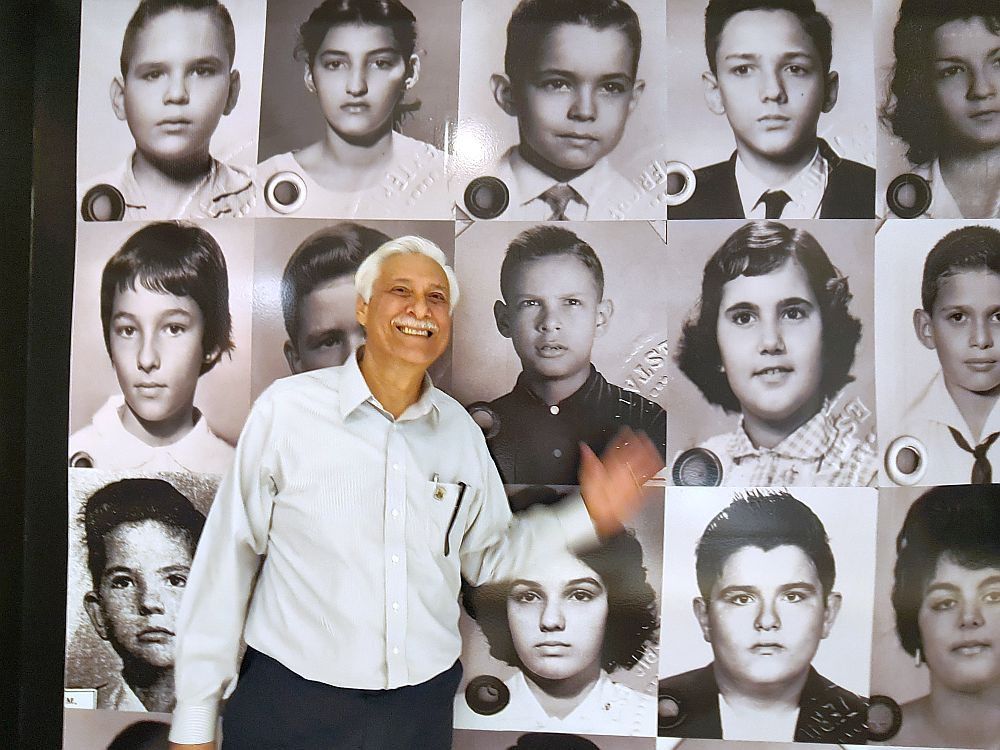

A veteran of the Bay of Pigs

After about 10 minutes, a man from the meeting approached me. His name is J.R. Lopez de la Cruz, and he was a member of Brigade 2506. Today he’s president of the Bay of Pigs Veterans Association. The men meeting in the conference room, he told me, were all veterans of Brigade 2506.

Mr. Lopez de la Cruz told me a bit about his own experience, clearly blaming the failure of the invasion on President Kennedy and his administration who, he said, kept changing the plan even as the invasion was happening. Cuban forces captured him and he spent two years in a Cuban prison, he told me. Later, when he got back to Miami, he made the US military his career, serving in the army, including two tours in Vietnam.

He pointed out something I hadn’t noticed before. I had seen the large wall covered with photos of the men who took part in the Bay of Pigs invasion. What he pointed out was that the center section of them, right behind the large table draped with an American flag, are photos of the “martyrs” of the invasion: the men who died. This room isn’t just a museum and meeting room, it’s a memorial as well.

I didn’t spend much more time in the museum, but was glad I went. The exhibits aren’t particularly impressive. What made my visit feel special was meeting an actual veteran and hearing the story from him.

Bay of Pigs Museum: 1821 SW 9th St., Miami. Open 10:00-16:00. Admission: free. Website.

Bay of Pigs Memorial

Right on Calle Ocho stands a monument in a park-like median strip at the corner of Calle Ocho and SW 13th Ave. It’s a simple marble pillar with an eternal flame on top, dedicated to those in Brigade 2506 who died in the invasion.

Another memorial just beyond it has a wider focus: those who fought as guerillas within Cuba against Castro’s government from 1960-1966. This one, in red, white and blue, the colors of both the Cuban and the US flags, depicts a man raising a rifle above his head.

A third memorial stands nearby (not visible in the photo above). Depicting a soldier carrying a rifle, it is dedicated to Tony Izquierdo, who died fighting the Sandinistas in 1979.

Other things to know about Little Havana

Of course Little Havana has plenty more to see, besides the museum and the two memorials.

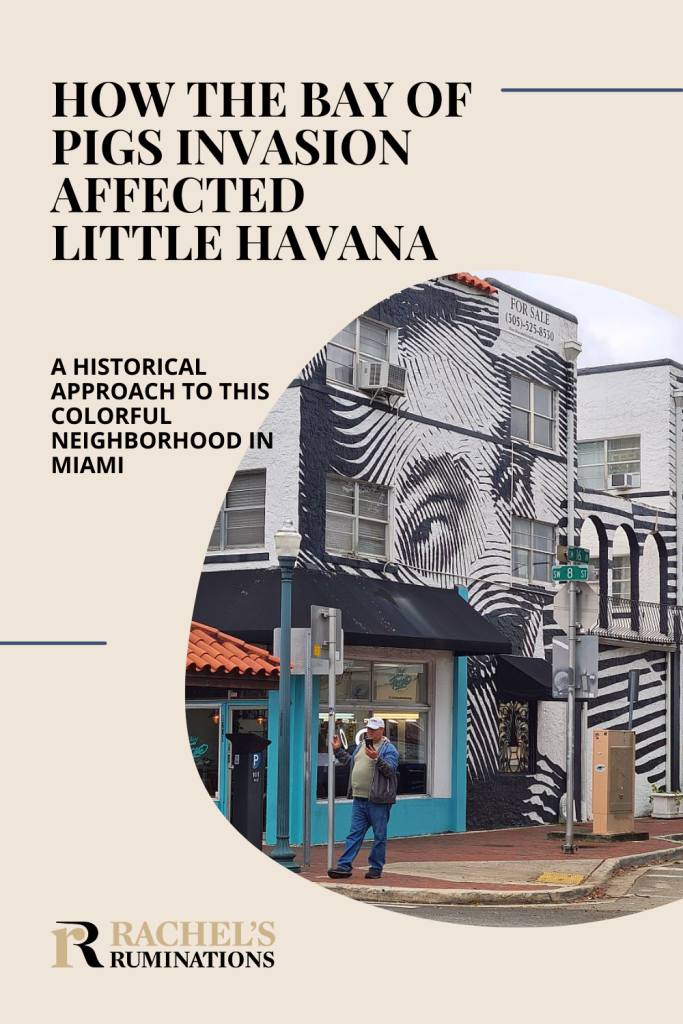

The center, particularly for tourism, of Little Havana is Calle Ocho (SW 8th St), though the neighborhood covers a much greater area. Stroll Calle Ocho for the highlights, but also some side streets to get a sense of the place as a neighborhood.

Domino Park

It’s famous for Domino Park, where the older Cubans hang out and play dominoes. This isn’t just a tourist thing – every time I walked by, several games were in session. The players were middle-aged or elderly, and the language of play was Spanish. No one seemed to mind the scattering of tourists watching, but they didn’t invite us to join in either.

Domino Park: corner of SW 8th St (Calle Ocho) and 15th Avenue.

Murals

Probably what makes Little Havana so popular with tourists are the colorful murals everywhere, especially along Calle Ocho. Murals even cover the local McDonald’s! Many of them are on storefronts or sides of buildings and advertise the particular shop or restaurant. Some refer to Cuban or Cuban-American culture – depicting well-known musicians, for example, or referencing the Bay of Pigs history.

Calle Ocho Walk of Fame

As you stroll Calle Ocho, notice the stars embedded in the sidewalk. (You can see two of them in the photo of McDonald’s above.) This is Little Havana’s version of the Hollywood Walk of Fame. It honors famous performers like Julio Iglesias, Gloria Estefan and others I hadn’t heard of before.

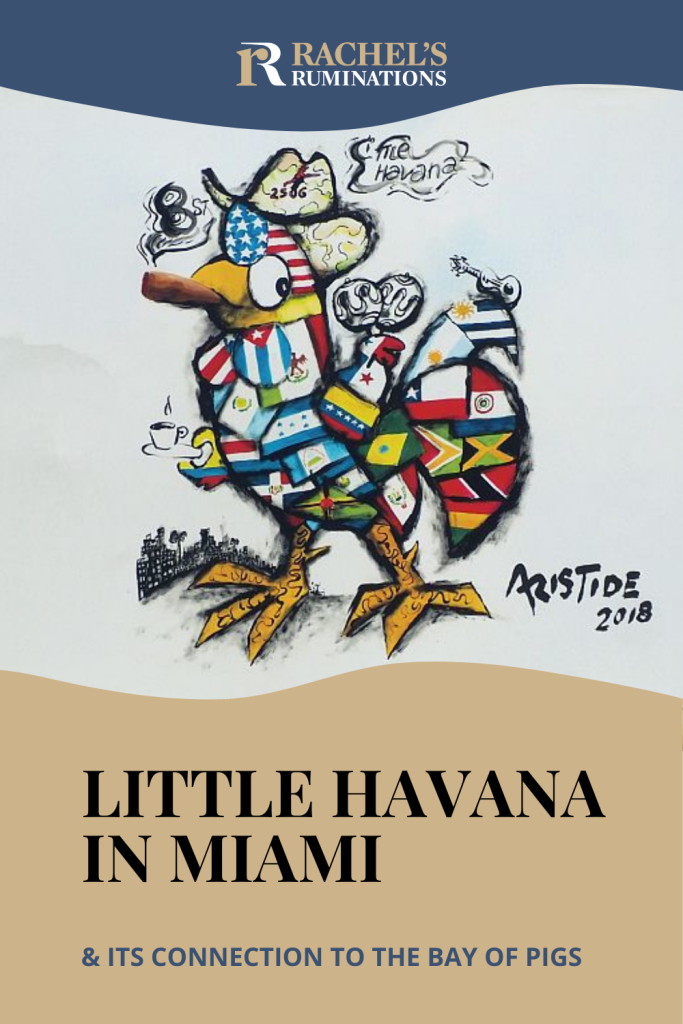

Roosters

Also notice the enormous roosters, painted in bright colors. No one seems to agree on why roosters have come to represent Little Havana, but you’ll see lots of them, each painted differently. Tourists love to pose with them.

Food

My introduction to Little Havana was through the excellent Little Havana food tour offered by Miami Culinary Tours. It was worth every penny I paid, given the quality and quantity of food combined with the expertise and knowledge of our enthusiastic tour guide, Gina. She didn’t just tell us about the food – though she told us plenty about that. She also related the history of Little Havana and its connection with Cuba.

The food was outstanding. We started with an elaborate explanation and tasting of Cuban coffee, then moved on to an empanada, a mojito, a Cubano sandwich (so good!), churros, and more.

The walking part of the tour only included a few blocks along Calle Ocho. Besides the Bay of Pigs memorial and Domino Park, we learned about the local Art Deco-style theater and art gallery, got explanations of several of the murals, and visited a cigar factory. Cigar production moved to Miami along with the exiles.

The American Museum of the Cuban Diaspora

Although it isn’t in Little Havana, I took an Uber to visit the American Museum of the Cuban Diaspora. Just going by the name of the museum, I hoped to learn more about the history of Little Havana and the Cuban community in Miami. The museum’s stated mission is “to tell the story of the Cuban Diaspora, though the eyes of its greatest artists, thinkers and creators.”

I’m not at all sure it really succeeds in that rather broad goal, but I did learn a thing or two there.

As far as I could tell, they really only have two exhibition spaces. One of them covers the Bay of Pigs Invasion. This exhibit gives more detailed information in a more professionally-curated way than the Bay of Pigs Museum does.

The other space is where the exhibitions change periodically. They’re often related to artwork produced in Cuba or by artists in the Cuban diaspora. When I visited, there was a temporary exhibit all about Operation Pedro Pan, which I’d never even heard of before.

Operation Pedro Pan

Operation Pedro Pan was a project to move 14,000 children from Cuba to the US starting in 1960 – in other words, right after the Cuban Revolution put Fidel Castro in power – and going on for almost two years. Private schools – mostly Catholic-run – in Cuba had been closed down and rumors were flying. Parents feared that Castro was planning to take their children away from them and indoctrinate them to support the Communist government.

The Catholic Church in Miami worked to facilitate sending the children to the US. The US government and anti-Castro private companies funded the effort. As with other Cuban emigrants to Florida in this period, the assumption was that this would only be a temporary solution since Castro’s regime was bound to crumble.

The children stayed at first in a sort of refugee camp near Miami. Eventually they were farmed out to foster homes and orphanages all across the country. They’re still referred to as Pedro Pans to this day. Most were eventually reunited with their parents starting in 1965, when the parents were allowed to leave Cuba on “freedom flights.”

Anyway, the rooms of this exhibition space illustrated Operation Pedro Pan, showing how it was carried out and organized and what happened to these children. The day I was there, two Pedro Pans were there too. One was a visitor, while the other, Javier Lloréns, was a volunteer and gave me a personal tour of the exhibition.

There wasn’t anything else to see at the American Museum of the Cuban Diaspora: just the exhibit about the Bay of Pigs and the temporary Pedro Pan exhibit. It was a bit disappointing. It seems to me there’s much more to say about the Cuban diaspora: where do Cuban-Americans mostly live now, besides Miami? What happened to the ones who emigrated later? Also, how has the Cuban culture become Cuban-American: has the traditional Cuban food changed? Has their religion? What about art and music? One temporary exhibit at a time just doesn’t seem enough.

American Museum of the Cuban Diaspora: 1200 Coral Way, Miami. Open Wednesday-Friday 10:00-17:00 and Saturday 10:00-16:00. Admission: $12. Website.

In any case, I think the key thing to know about the history of Little Havana is that it grew out of the Bay of Pigs invasion. That one event shaped the way this neighborhood gained its distinctive, world-famous character. And that single event is still very much present and remembered in Little Havana.

If you’ve visited Little Havana, I’d love to hear your impressions or recommendations. Add a comment below!