The Cambodian War Museum and Killing Fields, Siem Reap

Conflict in Cambodia, which lasted, more or less, from 1967 until into the 1990s, is still very much a presence in the country. Pretty much everyone was affected in one way or another. They or their family members might have fought on one side or the other. The Khmer Rouge may have forced them onto agricultural collectives, where they starved while cultivating rice for export. They or a family member may have stepped on a land mine, years after the war, dying as a result, or losing limbs if they lived. While the effort to clear the country of landmines continues, as of January 2023, about 1,970 square kilometers (761 square miles) still need to be cleared of landmines, unexploded ordnance and cluster submunitions, according to the Cambodian Mine Action Centre.

Disclosure: This article contains affiliate links. If you click on one and make a purchase or booking, I will receive a small commission. This will not affect your price.

When I visited Cambodia recently, the war in Cambodia seemed to be part of pretty much every story I heard. Even an 11th-century Hindu temple, Preah Vihear, included an altar to the last Khmer Rouge holdout.

History of post-WWII conflict in Cambodia

Some basic research led me to a general overview of what was really a series of wars and conflicts in Southeast Asia. To give a bit of background to these two museums, I’ve tried to summarize Cambodia’s history as best I can below:

- The Kingdom of Kampuchea: After the Japanese left Cambodia at the end of World War II, King Norodom Sihanouk proclaimed the Kingdom of Kampuchea. The French, who had been the colonial rulers, agreed by 1953 to hand over power.

- The Vietnam War and the Khmer Rouge: During the Vietnam War (1955-1975), the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) had bases over the border in Cambodia. US forces bombed them in 1969. It’s not clear what the King’s position was on the NVA using Cambodian territory, but he did object to the US’s bombing campaign, wanting to stay neutral. At the same time, an insurgency against the king was gaining strength, led by the Communist Party of Kampuchea. Sihanouk called them the Khmer Rouge.

- General Lon Nol: In 1966, General Lon Nol was elected and formed a new right-wing government. Both the newly-elected government and the army were not happy with King Sihanouk’s rule.

- A coup and the Khmer Republic: A military coup led by General Lon Nol ousted Sihanouk in 1970. The new regime ended the monarchy and named the country the Khmer Republic. They told the NVA to leave Cambodia.

- US involvement: The US started helping the Cambodian army under Lon Nol. Not surprisingly, this pissed off both the North Vietnamese and the Khmer Rouge, who attacked the new regime.

- The North Vietnamese and the Khmer Rouge: The North Vietnamese succeeded in taking over a large part of the country east of Phnom Penh. They gave the territory to the Khmer Rouge. The US military increased bombing in Cambodia.

- Khmer Rouge gains: Meanwhile the Khmer Rouge was gaining strength and taking more territory. The elected government (Khmer Republic) only held onto power in the larger cities.

- Khmer Rouge victory: In 1975, the Communists under the Khmer Rouge conquered Phnom Penh. They installed their own government under the leadership of Pol Pot.

- The Khmer Rouge regime: The Khmer Rouge era lasted from 1975-1979. It was devastating because the new government forced millions of urban dwellers to the rice fields in the countryside to work on collective farms. The Khmer Rouge operatives applied unspeakable cruelty to make this happen. Something like 1.5-2 million deaths resulted from their policies through outright extermination or through torture and starvation.

- Vietnamese takeover and the People’s Republic of Kampuchea: In 1979, Vietnamese forces, who had broken with the Khmer Rouge soon after the Khmer Rouge took over, invaded and took over Cambodia. They established the People’s Republic of Kampuchea.

- The Cambodian Civil War: The Khmer Rouge retreated to the north and kept up a guerilla resistance, together with several other resistance groups. The Cambodian Civil War led to more deaths and displaced many Cambodians to refugee camps.

- Peace: A peace settlement was signed in 1991. The last surviving Khmer Rouge members didn’t surrender until 1998.

My husband and I spent a week in Cambodia recently. Our goal was to see all of the UNESCO sights in the country. All four of them – the most well-known is Angkor, home of Angkor Wat – pre-date the 20th-century conflicts, but the wars kept coming up like a shadow in the background. I wanted to piece this history together, so when I had some time in Siem Reap – we didn’t go to Phnom Penh at all – I decided to go learn what I could.

The Cambodian War Museum

I’ll say right at the start that this museum disappointed me. I had hoped to learn something about this series of conflicts, but this museum, despite its name, isn’t a place to learn about the wars. Rather, it focuses solely on the weaponry used in the wars.

Founded in 2001, the Siem Reap War Museum did not do well, getting very few visitors. In 2013 a new manager took over, Richard Esselaar, and the museum’s name changed to War Museum Cambodia. A small tornado damaged it the next year, but since then it has gained visitors. I did not see much evidence of this when I visited. However, it was a very hot early afternoon on a weekday, so that might explain why there so few visitors besides me.

The musem has an exhibition hall at the entrance, but it’s empty. All that was there was a long counter – with no one staffing it – a cot – with a woman asleep on it – and an electric fan. There were no informational signs providing any background about the Khmer Rouge era or the civil war after it.

Apparently the museum sometimes provides a free guide – a former soldier of these conflicts – to give a tour of the museum, but none were available the day I visited. There was no printed matter to replace what a tour might have offered. I’m assuming that if a tour guide had been available I might have gotten more out of my museum visit.

Book accommodations in Siem Reap here.

The Cambodian War Museum’s collection

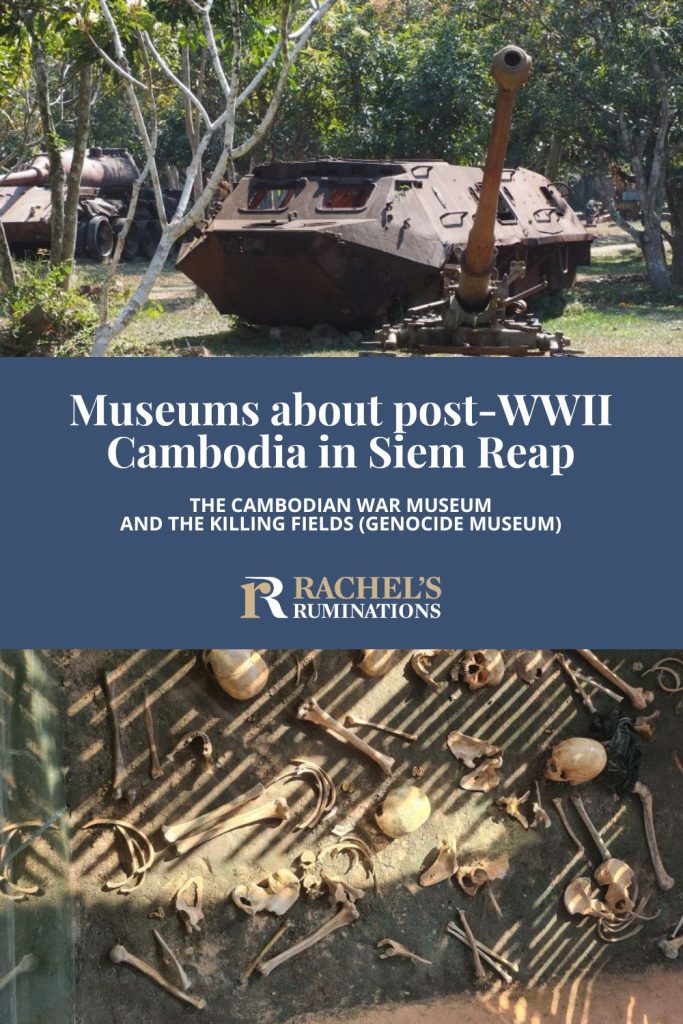

Behind the exhibition building is a large field, dotted with trees and with old military hardware. I saw weapons of many types. I know nothing about weaponry, but I think the collection included more than one anti-aircraft gun, as well as machine guns, rocket launchers, cannons, and various other such large guns. There was also a vast array of vehicles: mostly things like tanks. At one end, near the entrance, stand a Soviet-built jet fighter aircraft MiG-19 and a helicopter Mil Mi-8, also Soviet, neither in good shape.

Only the guns came with signs explaining them. The signs generally included where they were made – usually either the US or the USSR – when they were used and where they were found. As an example, one sign reads: “D30-122mm. Arttilery D30.122mm made in USSR. 1985. 4.37 m lenght. Size 122 m. Fighting power target 16 km. Explosion 150 m around. used in Cambodia since 1987 and discovered on 1998 at Siem Reap Area” [sic]. Some of the tanks have some indication of whether they were used by the US army, the Khmer Rouge army, the NVA, or the Cambodian army. They range in age from World War II up to the 1980s. All these war relics stand – all of them rusted, some of them damaged in fighting – on more than two hectares of land.

Most of the collection of the Cambodian War Museum was, essentially, salvage that has been saved from scrap dealers selling whatever metal they find for scrap. (I did not learn this at the museum, by the way, but afterwards, through my own online research.) Apparently, collecting these relics was no easy feat. Many items in this unique collection were in dense jungle areas and were extremely difficult to move and transport to this war remnant museum. Saving them was the original purpose of the museum.

As far as I can see, though, the museum’s collection of war machines is gradually decaying into the ground. Some of them stand on low concrete platforms, and a network of small trenches crisscrosses the field to channel water away during the rainy season. But that won’t stop them from getting rained on, which means, it seems to me, that they’ll eventually rust away.

The Landmine House

Within the grounds of the Cambodian War Museum, in a separate building, an exhibition about landmines opened in 2018 called the Landmine House. In a single octagonal room, a collection of different land mines are on display. Most are just sitting on the floor or leaning against the walls. They originate from different makers and different countries and, unlike the collection of weaponry outside, here detailed signs explain all aspects of landmines. They explain how each sort works, along with stories of individual landmine victims, accompanied by sometimes lurid photos. One wall explains the different ways mines and other unexploded ordnance can be cleared and also about various organizations (NGOs) that work on mine clearance or on helping victims.

The Landmine House also contains some small arms, though these aren’t labeled or explained in any way. I assume none of the landmines or guns are in working order, considering how casually they are displayed.

Killing Fields Siem Reap

I had arranged for my tuktuk driver to wait for me outside the Cambodian War Museum. When I returned to find him in the parking lot, he suggested that I visit the Killing Fields to learn more about the era. That surprised me – I hadn’t heard of Killing Fields in Siem Reap – only about the more famous and more visited Killing Fields in Phnom Penh, properly called Choeung Ek Genocidal Centre. He assured me that there was also one in Siem Reap, and I agreed gladly to go there. After all, I was coming away from the War Museum knowing little more about Cambodian history in general or the various horrific conflicts of the 20th century than I started with, apart from some details of landmines and their effects.

The Killing Fields, also known as the Genocide Museum and as Wat Tephothivong Memorial Site, is located in a compound containing a number of buildings, a temple and monks’ quarters. The museum itself includes a series of buildings where text and photos tell the history, mostly focusing on the period of Khmer Rouge rule. Fortunately, it also fills in visitors on the period before that. This allows a better understanding of the sequence of events that led to this particularly cruel period.

The exhibits are nothing fancy: just text and photos and drawings. Nevertheless, it tells the story well. It begins, in the first building, with the story of an individual who went through all sorts of terrible experiences under the Khmer Rouge: forced labor, arrest and torture, more forced labor, etc. In succeeding buildings it tells the general 20th-century history of Cambodia.

Mass graves

Once visitors have the basic background, the museum moves on to an outdoor area where it tells the story of this place and what happened here. Three mass graves have been excavated on this site. They are partly visible in a sunken, shaded area, and some human bones and pieces of clothing found in the graves have been left exposed on top. It’s a grim sight. Signs above the graves explain what each bone or artifact is: “The skull of a female victim, aged between 35-45 years.” “A piece of black pants made of raw yarn.” And so on.

A small shrine stands in the open plaza next to the mass grave and contains more of the excavated bones. A sign explains that the original stupa, built by the children of the dead in 2006, was too small to house all of the skeletons. This shrine is the rebuilt stupa, holding about 800 skulls.

The open-air plaza next to the mass grave and the shrine holds a series of large signs which take up the story of the atrocities that happened here. Some are on particular sub-topics like forced marriages under the Khmer Rouge, the general history of the Khmer Rouge and its ideology, Pol Pot, and information about the Khmer Rouge’s policy of forced communal rice cultivation. There are a few informational signs that are particularly gruesome, such as the one that shows two recipes used in the communal kitchens here at the Killing Fields. One is for porridge and the other for soup, but both include human meat from those executed here.

The Killing Fields compound

The memorial occupies the grounds of a Buddhist monastery and temple. Next to the temple was a large building originally used as a hospital for the Chinese and Cambodians who built Siem Reap international airport. The hospital building became a resort for the French, then a military site for the Khmer Republic’s army under Lon Nol. The Khmer Rouge took it over and used it as a prison. At the same time they took over the temple and monastery next door. Their ideology was anti-religion, and they forced monks to work and to give up their monkhood – not just here but everywhere in the country.

The executions took place right outside of the prison and the temple. They executed people for imagined crimes like working for the CIA or KGB or trying to escape their work details or any other supposed crimes. The corpses were buried quickly, presumably by convict laborers, right on the site in mass graves.

Today it looks like a Buddhist center occupies the ground floor of the former prison. The upstairs appears empty. The active temple next door looks new, as do the rows of monks’ houses.

The Cambodian War Museum or the Genocide Museum?

While Siem Reap’s war museum is apparently the only war museum in Cambodia, the Killing Fields is a much better place to learn about Cambodia’s war years.

If the weaponry used in the decades of armed conflict interests you – and especially if you already know something about tanks, anti-aircraft guns and the like, you should certainly stop at the Cambodian War Museum. Unless it’s a particular interest of yours, it’s unlikely to take you more than about a half hour to see it all.

The Genocide Museum, however, is the best place in Siem Reap to learn about the Khmer Rouge period and to get an overview of the upheavals that preceded their rule as well. It’s a moving and fitting memorial to the people of Cambodia who suffered during this period.

While I didn’t go there, I should also point out that there is a Cambodia Landmine Museum 25 km (15 mi) outside of Siem Reap. If you’re going to see Banteay Srey Temple, part of Angkor UNESCO site, they would combine well.

This full-day tour includes all three museums and comes with a tour guide.

Zoom in on the map below to find accommodations in Siem Reap. I’ve marked the two museums on the map as well.

Getting there

Both museums are within the city of Siem Reap, but not in the center of town.

Getting to the Cambodian War Museum

The War Museum is about 5 km (3 mi) to the northwest of the city center of Siem Reap. It’s about a ten-minute drive, but more like twenty minutes if you take a tuktuk like I did.

Getting to the Killing Fields

The Genocide Museum is about half that distance, and it’s north of the city center. That’s about six minutes by car and 10-15 by tuktuk. It’s just off the main route to Angkor Wat, part of the Angkor UNESCO World Heritage site, so it might combine well on your way to or from Angkor Wat

If you decide to see both, it’ll take about ten minutes to drive between them. By tuktuk it’ll take more like 15 minutes. When you first set off in a tuktuk or taxi, agree a price with the driver for both destinations and for waiting for you at each one. In my case, since we only originally agreed on one destination, I offered extra for the trip to the second museum and for him to wait while I was there as well to drive me back to my hotel.

Alternatively, a number of tours are available that include both these museums.

Have you been to either of these museums in Siem Reap? Add your thoughts or advice below!

My travel recommendations

Planning travel

- Skyscanner is where I always start my flight searches.

- Booking.com is the company I use most for finding accommodations. If you prefer, Expedia offers more or less the same.

- Discover Cars offers an easy way to compare prices from all of the major car-rental companies in one place.

- Use Viator or GetYourGuide to find walking tours, day tours, airport pickups, city cards, tickets and whatever else you need at your destination.

- Bookmundi is great when you’re looking for a longer tour of a few days to a few weeks, private or with a group, pretty much anywhere in the world. Lots of different tour companies list their tours here, so you can comparison shop.

- GetTransfer is the place to book your airport-to-hotel transfers (and vice-versa). It’s so reassuring to have this all set up and paid for ahead of time, rather than having to make decisions after a long, tiring flight!

- Buy a GoCity Pass when you’re planning to do a lot of sightseeing on a city trip. It can save you a lot on admissions to museums and other attractions in big cities like New York and Amsterdam.

- Ferryhopper is a convenient way to book ferries ahead of time. They cover ferry bookings in 33 different countries at last count.

Other travel-related items

- It’s really awkward to have to rely on WIFI when you travel overseas. I’ve tried several e-sim cards, and GigSky’s e-sim was the one that was easiest to activate and use. You buy it through their app and activate it when you need it. Use the code RACHEL10 to get a 10% discount!

- Another option I just recently tried for the first time is a portable wifi modem by WifiCandy. It supports up to 8 devices and you just carry it along in your pocket or bag! If you’re traveling with a family or group, it might end up cheaper to use than an e-sim. Use the code RACHELSRUMINATIONS for a 10% discount.

- I’m a fan of SCOTTeVEST’s jackets and vests because when I wear one, I don’t have to carry a handbag. I feel like all my stuff is safer when I travel because it’s in inside pockets close to my body.

- I use ExpressVPN on my phone and laptop when I travel. It keeps me safe from hackers when I use public or hotel wifi.